For most of the last four decades, investors have enjoyed a giant convergence trade.

It was a convergence of economic policy direction, which led to a convergence of generally lower inflation and interest rates—generating higher trend economic growth rates—primarily through increasingly free-wheeling globalisation and free trade.

The trigger for this benign cycle was a generalised geopolitical view that the Cold War was over for good, and most could benefit. We did not question the long-term sustainability of this wonderland, because we believed that economic growth could appease even longstanding ethnic/territorial resentments.

A key driver of the ensuing lack of interest in defence has been the widespread belief that globalisation’s benefits, via contributions to prosperity and economic growth, had succeeded in establishing a new paradigm whereby war was unnecessary, and states could simply focus on economic development.

The reversal

The abrupt reversal of the ‘peace dividend’ – most notably in Europe amid Russia’s war on Ukraine – and the deployment of new military technologies like drones and electronic signal jamming has fueled a rapid acceleration of investment in defence.

These investments range from the upgrading of hardware through the modernisation of equipment, the updating of training to absorb the lessons of Ukraine and Gaza, the recalibration of financing and supply chains, and investments to rapidly increase domestic production capacity.

The commitment by European NATO members to invest over US$400 billion annually[1] for at least the next decade is just the start, as the recent growth in the number of private equity and public markets mandates suggests.

Unprecedented spending, again…

Defence spending in 2023 reached its ninth successive annual record, totaling US$2.4 trillion.[2] This amount represents a 36% increase over the last decade.

Over the next six years, NATO spending alone is estimated at US$8.9 trillion, of which US$3.2 trillion is from European NATO members and Canada.[3] It works out to be around US$500 billion a year, rising to US$600 billion a year in 2029.

We believe these developments have reopened an investment opportunity in the defence sector.

A much-changed industry

The last time a defence stock was among the top 10 performers of the S&P 500 Index was in the 1980s. The global defence industry has changed a lot since then.

In the 1980s, there were estimated to be more than 3,000 companies in what was known as the “military-industrial complex”. Tenders often received hundreds of proposals.

Today the sector has consolidated, with contracts tiered by specialisation as well as by geography. There are very few companies that can supply high-ticket, high-specification hardware.

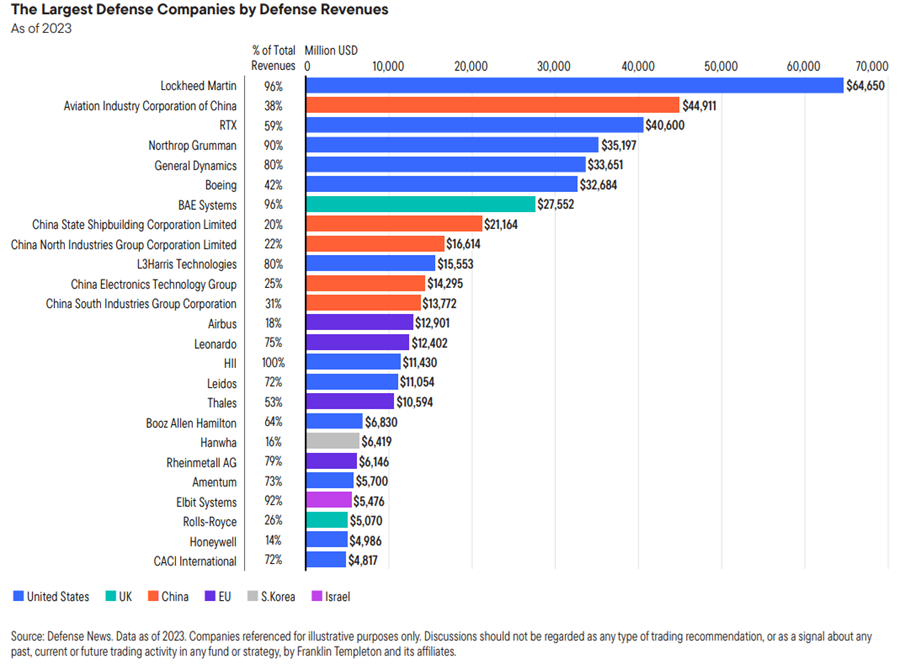

Exhibit 1: The United States and China dominate arms production

Source: Top 100 | Defence News, News about defence programs, business, and technology. Defence News. As of 2023.

Yet there is also a plethora of companies providing newer defence capabilities, and the investment universe provided by the ‘new look’ defence sector is significant.

This ranges from very large companies like Microsoft, which provides cutting-edge defence capabilities against cyberattacks, to small companies like QinetiQ[4], which provide military robots, risk evaluation across air, land and sea, and cybersecurity solutions.

The obvious and not-so-obvious winners

The obvious winners from this fast-growing spend on defence equipment are the usual suspects—the large, established players with strong balance sheets and stronger relationships with their buyers around the globe.

There is also a less-appreciated universe of French, Italian, German and South Korean producers who are gaining market share, particularly with buyers in Europe and southeast Asia.

European manufacturers, for example, will take market share from Russia over the next decades, as India’s gradual modernisation gathers pace and the managed decline in dependence on Russian arms accelerates.

Furthermore, Japanese companies have been banned from exporting weapons since the mid-1960s under the “Three Principles on Arms Exports” policy.[5] This ban is now under revision, with a potential reversal on the cards, which would open up lucrative new markets for Japanese defence companies.

Potential mispricing

The investment case in defence is built on concrete evidence of plans for capital expenditure and research and development programs in a wide variety of subsectors. Three elements of the investment case appear to be mispriced:

1. The magnitude of the public and private sector capital expenditure in defence.

Many countries are still in the process of reviewing their defence architecture in the light of lessons learned in Ukraine and the Middle East.

This process will result in a new set of priorities and requirements to suit modern asymmetric warfare, across multiple domains. It seems prudent to assume that the amount of capital investment will be significantly higher than currently expected.

2. The longevity of this investment theme seems underappreciated.

The combination of changes in capabilities that militaries now require to defend their countries is enormous in scale and in reach, which implies a decades long runway.

3. The wide range of opportunities for investors.

As the template defence structure changes, so does the definition of the defence industry.

The range covers both the traditional (non-proscribed armaments) and the exciting new technologies (LEO Satellite mapping/communications, AI enhanced data management programs, etc.). Much of this will doubtless be transferred to civilian applications.

Finally, there is a group of companies in a variety of geographies (South Korea, India and Japan) that stand to benefit from this investment theme.

[1] Source: “Defense Expenditure of NATO Countries.” NATO, 2014-2024. June 17, 2024.

[2] Source: The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The SIPRI Yearbook 2024.

[3] Sources: IMF, NATO, Franklin Templeton Institute calculations. (IMF GDP projections and NATO members’ statements on future defense spending as % of GDP). There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realised,

[4] QinetiQ evaluates, integrates and secures mission critical platforms, systems, information and assets.

[5] Source: “Japan’s Security Policy.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Japan’s Security Policy. December 5, 2023.

Kim Catechis is an Investment Strategist with the Franklin Templeton Institute. Franklin Templeton is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

For more articles and papers from Franklin Templeton and specialist investment managers, please click here.

This article is an abridged extract from Franklin Templeton’s recent white paper “Deep waves: The paradoxical trinity of defense.” Go here to read the full version and important disclaimers.