With the strong growth in index funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) in the Australian marketplace in recent years, debate is again swirling on the benefits of active versus passive investment management. Some commentators have suggested that index-oriented investments are merely for ‘dumb’ investors, who have no real skills in picking mispriced securities likely to outperform the market. If this were true, it would follow that these investors are leaving money on the table. By either investing in the development of these skills – or hiring talented active managers – they could produce better returns. It has been suggested that over the very long run, ‘sensible investing’ in ‘quality’ stocks will beat an index. How true is this?

The evidence suggests most active managers don’t outperform the index

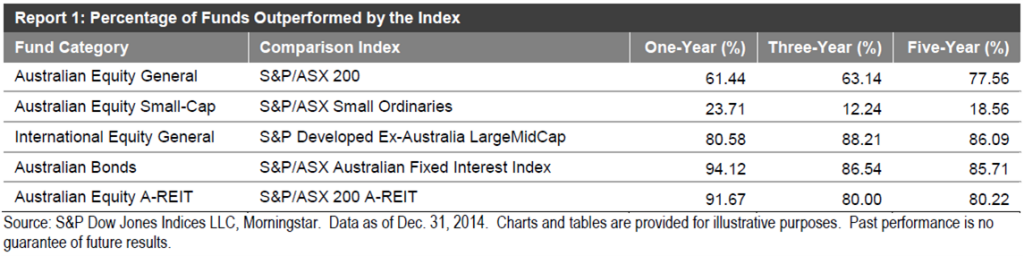

Fortunately for participants in the ongoing active v passive debate, whether active managers outperform a market-cap weighted index is ultimately an empirical question. The evidence seems overwhelmingly in favour of passive investment, both in Australia and overseas. According to the latest SPIVA Australia Scorecard by S&P Dow Jones Indices, charted above, about 78% of active Australian general equity managers underperformed the S&P/ASX 200 Index over the five years ending December 2014. The performance of local international equity managers, Australian fixed-income managers, and listed property managers was somewhat worse. Over the latest three year period, the scorecard was slightly better for Australian equities active managers, although 6 in 10 managers still underperformed.

Even if active managers were able to consistently outperform the market, moreover, their degree of outperformance would need to exceed their management fees to beat some of the low cost ETFs and index funds available. As an example, a fund that charged a 1% p.a. management fee plus a 10% outperformance fee (charged before deduction of fees) would need to generate a return of 10.95% p.a. to offer the same return to an investor in an index product that rose by 10% in the year and charged a management fee of 0.15% p.a.

Active outperformance is unlikely to persist

Of course, the above evidence suggests that some active managers can outperform the market. The challenge investors face, therefore, is in identifying these superior managers. Picking active managers that consistently outperform is not easy. As the old truism goes, past performance is not a great indicator of future performance.

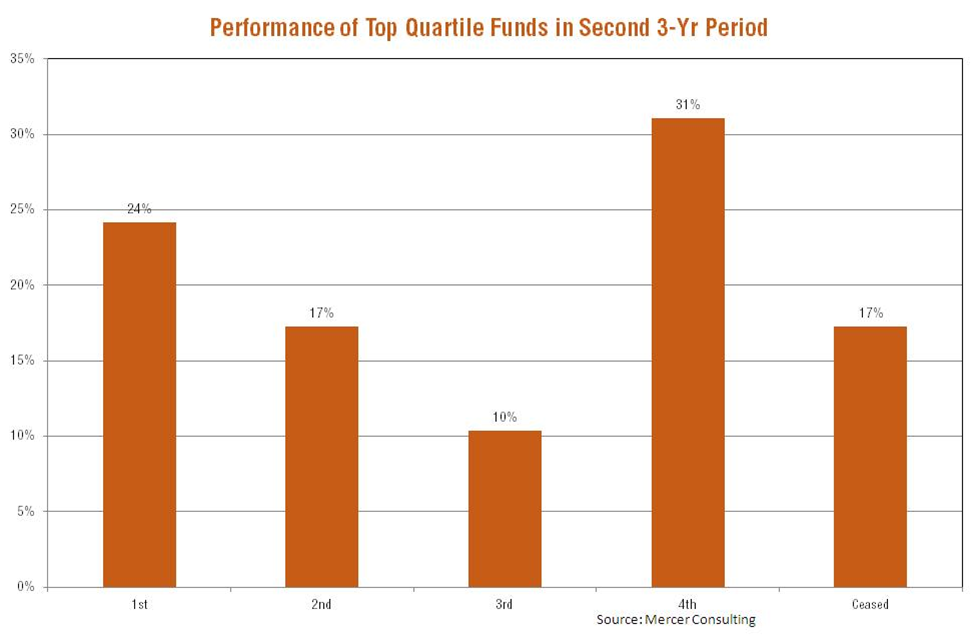

The chart below, for example, is based on research on Australian active equity managers from Mercer Consulting which tracked the performance of investment managers across two three-year investment periods. How many of the funds that performed well in the first period also performed well in the second period? In other words, how persistent was outperformance?

Only 24% of the 29 funds identified by Mercer as enjoying top quartile investment performance in the three years to September 2010 were also able to produce top quartile performance in the three years to September 2013. In fact, statistically speaking, the most likely scenario (31%) is for a top quartile performer in the first period to end up becoming a fourth quartile performer in the second period. Meanwhile, almost one in five of these top performing funds ceased operation (or were merged/taken over) in the second three-year investment period.

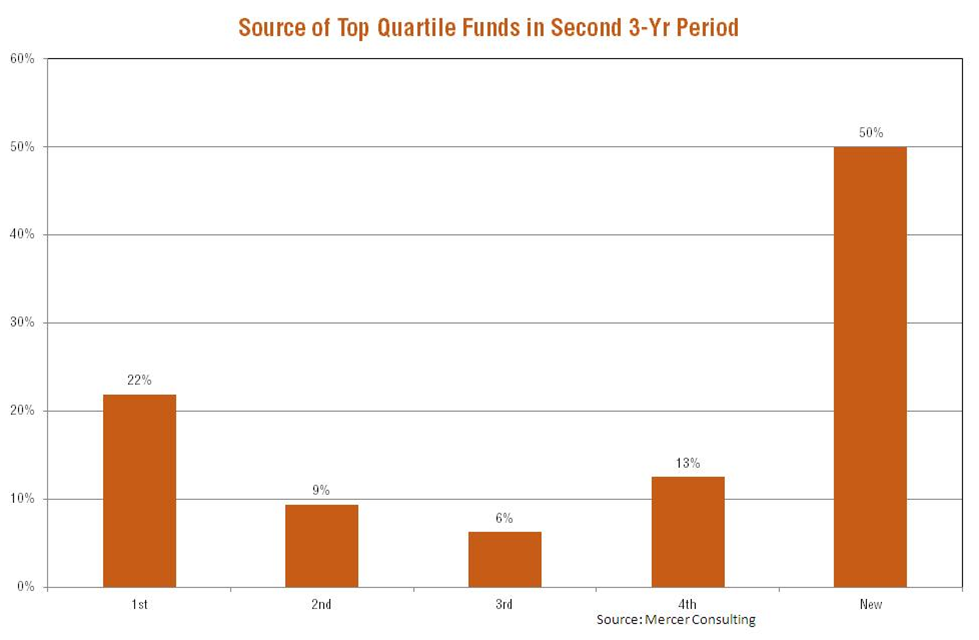

Indeed, according to the Mercer Survey, of the 32 funds with top quartile performance in the three years to September 2013 (among 126 funds covered), 16 – or 50% – of these funds were new to the market.

Active managers dominate the market so it’s hard to outperform

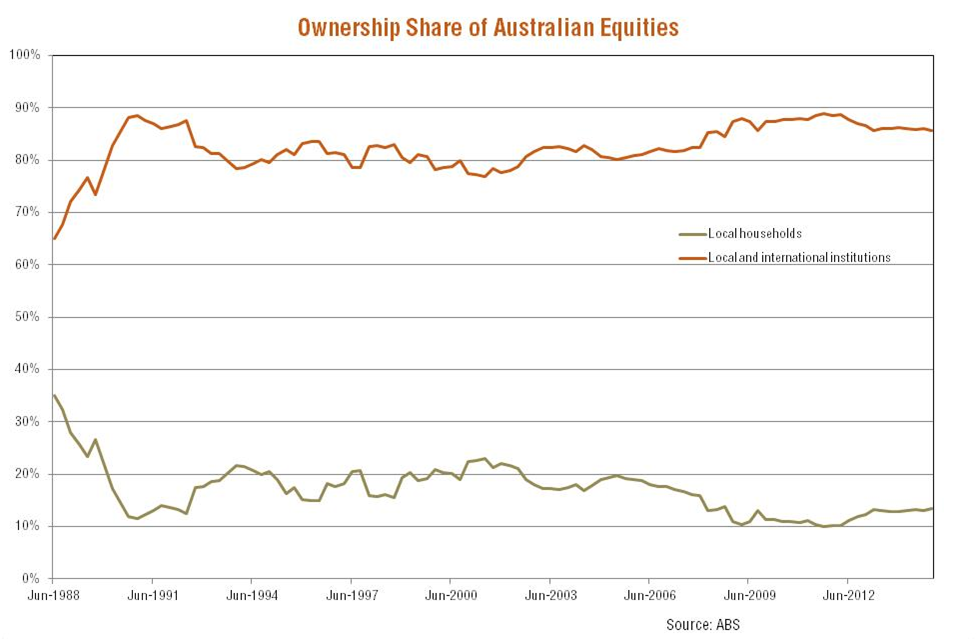

Due to the fact that institutional money – which is still predominantly active in nature – tends to dominate ownership and therefore trading in the Australian equity market, not all managers can outperform the market all of the time. This is because for every ‘winning’ trade, there will equally be a ‘loser’ on the other side. As seen in the chart below, of the $1.6 trillion worth of ‘listed and other’ equities in Australia as at end December 2014, a whopping $1.4 trillion – or 83% – was owned either by domestic institutional investors, or foreign owners (which are also largely institutional). Households directly owned only around $200 billion, or 13%. The collective attempt of active managers to beat the market is akin to a zero-sum game.

There is more to indexes than tracking cap weights

Due to the development and continued innovation in indexation, there are now a number of indices which recognise the limitations of traditional cap weighted indices, including some offered in Australia by BetaShares. These ‘smart beta’ indices, such as fundamental weighted indices, combine the benefits of index funds (i.e. low cost, transparent, diversified, rules based) along with the potential to outperform the market cap benchmark.

We’re a long way from passive investment distorting the market

There has been some conjecture that the continued growth of index investing and ETFs may contribute to potential market distortions. We are a long way away from that. According to Morningstar Research estimates, passive investment strategies account for around 8% of Australian managed funds. At these levels it’s unlikely rebalances in such products will be a major influence on market pricing. With only about $18 billion funds under management, Exchange Traded Products account for only about 0.7% of the $2.4 trillion managed funds industry as at March 2015.

Even in the United States – where passive investment is estimated to account for a much larger 24% of funds under management in 2013 – it still seems evident that active managers have a hard time beating the market. According to S&P’s latest survey, for example, 88% of large-cap US managers failed to beat the S&P 500 index in the five years to the end of 2014.

There is no doubt that there do exist a select number of active managers who have a strong track record of persistent outperformance. We firmly believe that active management has a role to play in investors’ portfolios, and often find ourselves discussing how ETFs can be used in combination with high quality active managers. However, when considering the active versus passive debate, we believe it’s important to be armed with the empirical facts.

David Bassanese is Chief Economist at BetaShares, a leading provider of Exchange Traded Products on the ASX. This article is general information and does not address the personal needs of any individual. This article was originally published on the BetaShares blog.