(This article was originally published in 2014, but given the attention on FoFA in the Royal Commission, we highlight it again as excellent background to the current circumstances).

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, many Australian investors suffered losses as a result, either in part or substantially, of financial advice that was subsequently found to have been deficient. In many instances these deficiencies were exacerbated by conflicts between the giving of the advice and the nature of the remuneration received by the adviser.

As a result of a number of high profile collapses, including Storm Financial and Opes Prime, the Labor Government launched an inquiry into laws governing the provision of financial advice. The findings of the Ripoll Inquiry, delivered in November 2009, formed the core of the then-Government’s legislative response, released in April 2010 under the moniker Future of Financial Advice (FoFA). The FoFA changes became law in June 2012, applying on a voluntary basis from 1 July 2012. Compliance with FoFA became mandatory effective 1 July 2013.

What is all the fuss about?

Whilst FoFA encompassed a variety of changes, the most contentious reforms related to:

1. The introduction of a statutory client best interest duty

Prior to FoFA advisers had to ensure compliance with a set of suitability rules when giving advice. FoFA introduced a statutory requirement to ‘act in the best interest of the client in relation to the advice’. Compliance with this duty could be demonstrated via a seven step statutory process known as the safe harbour provisions.

2. A ban on conflicted remuneration

FoFA introduced a ban on all forms of conflicted remuneration, being any payment that could influence the product recommended, or advice given, to a client. The ban applied to commissions and precluded both the payment and receipt of conflicted remuneration (with a few exceptions including for insurance advice) between product manufacturer and advice provider.

3. Enhanced ongoing client engagement and fee disclosure requirements

These changes were designed to empower clients and encourage fee transparency. For clients first engaged after 1 July 2013, advisers would need to receive permission every two years, via an Opt-In statement, to continue the provision of ongoing advice. In addition, advisers would need to provide an annual Fee Disclosure Statement (FDS) to all ongoing clients (irrespective of when first engaged), with the FDS providing details of services rendered and amounts charged over a preceding 12 month period.

An orphan soon after birth

FoFA had not long been in full effect when the September 2013 federal election resulted in a change to a Liberal Government. In December 2013, the new government announced a package of measures to amend FoFA, citing a desire to “reduce compliance costs for small business, financial advisors and consumers who access financial services”. The package of changes included:

- the removal of the Opt-In requirement

- restricting the FDS requirement to clients first engaged after 1 July 2013

- watering-down the best interest duty (via the removal of a ‘catch-all’ provision)

- exempting general advice (advice given without detailed knowledge of a person’s financial needs, objectives and circumstances) from the ban on conflicted remuneration.

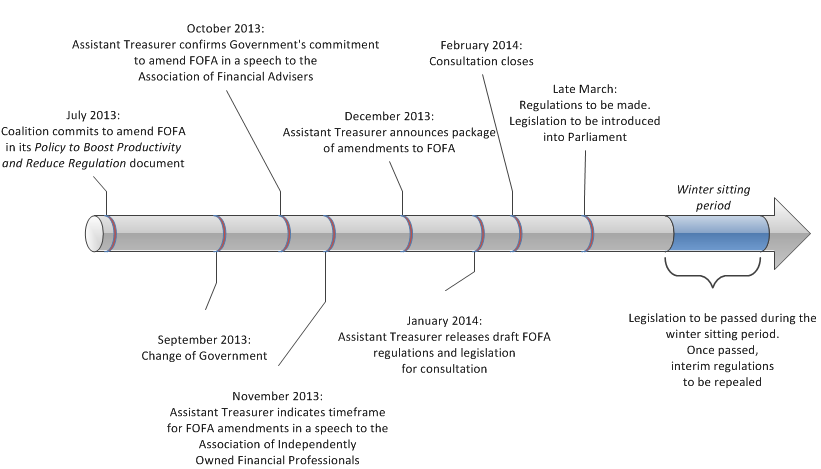

A schematic of the FoFA amendment timeline, as expected by the Liberal Government, appears below:

HC Figure1 281114

Source: Revised Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014

The Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014 was introduced into the House of Representatives in mid-March 2014 and was met, as expected, with vociferous opposition from members of the former government. To expedite matters the government, in late June 2014, pushed its FoFA amendments through via regulation.

This regulation applied with effect from 1 July 2014, and so allowed advice to be provided under the amended FoFA obligations from that date. It was meant as an interim measure until such time as the amending Bill became law. A fait accompli, one would have thought.

Senate disallows FoFA

Entering the Senate for a second time in early September 2014, the FoFA Bill faced almost immediate delay in an economics committee. Press coverage was openly critical of the softening of both the best interest duty and the conflicted remuneration provisions. Taken together these amendments appeared to favour the large banks, as both creator and distributor of financial product via branches and bank-owned financial planning businesses.

Through October and into November 2014, the FoFA Bill was subject to much negotiation, including the establishment of a National Register of Financial Advisers. Just when it looked likely to pass into law, on 19 November 2014 a motion to disallow the Corporation Amendment (Streamlining Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014 was put forward by the opposition and garnering the support of Senators, both independent and from other parties, was upheld.

The disallowance means that the FoFA amendments are effectively nullified, with the FoFA laws as at 1 July 2013 applying forthwith. With the potential for enormous disruption in the advice industry, ASIC has stated that it will take a “practical and measured approach to administering the law” and will “work with Australian financial services licensees, taking a facilitative approach until 1 July 2015”.

Ultimately then, the government could not shake the perception that its FoFA changes would have benefited the ‘big end of town’ at the expense of consumer protection. Coinciding press coverage of poor advice practices at two of the largest banks in the country, and of losses suffered in agribusiness schemes promoted by advisers, only served to reinforce this disquiet.

Towards a day when the ‘Fo’ in FoFA is redundant

FoFA has already changed the advice industry. In 2011 ASIC found that on average only 10% of total revenue generated by the 20 largest planning businesses was paid directly by the client. By 2013 this figure stood at 36%, with two groups receiving over 90% of revenue directly from clients.

With the FoFA amendments blocked, will the additional compliance burden result in costs to the advice industry of an additional $190 million a year, as estimated in the Bill’s explanatory memorandum? Even if this were the case, for an industry generating some $4 billion in annual revenue it would represent a small margin contraction. Whilst not insignificant, it might be the price required to address the trust deficit if the financial advice industry is to genuinely become a profession.

Where to from here? As the former Chair of the Financial Planning Association, Matthew Rowe, told the 2014 FPA Conference last week, that when discussing legislative changes with politicians, “… we need to be able to do that through the lens of what’s in the public’s best interests”. That’s where, so far, the battle has been lost.

Postscript

When I wrote this article in late 2014, it was to highlight how the FoFA laws had come under sustained lobby group pressure for legislative reform, yet had survived broadly unscathed. To my mind FoFA was (and remains) the single most important set of advice industry reforms of the past two decades, legislating that which ought to be second nature to any genuine fiduciary. Act in your client's best interests, be transparent in your dealings and remuneration, and avoid, to the maximum extent possible, any conflicts that could colour your advice. Pretty simple stuff. Or so I thought.

Perhaps I was naive to think that the advice industry would reinvent itself completely post-FoFA. Even so, I've been stunned by the revelations now surfacing at the Hayne Royal Commission; of financial advice practices and behaviour so egregiously dismissive of the spirit of the FoFA reforms. It would, however, be grossly unfair to brand the entire advice industry as lacking a moral compass. The vast majority of advisers genuinely want to do the right thing by their clients, and I believe, in time, what was once a product distribution industry will morph into a profession in its own right.

Harry Chemay is co-founder of robo-advice platform Clover.com.au.