Published in 2001, my book Naked Among Cannibals examined how banks had fallen from revered to reviled within a couple of decades. Over the subsequent few years, the finance industry seemed to be gradually winning back the trust of the public, with market research showing improving customer satisfaction and better ratings for ‘ethics and honesty’. But events relating to Storm Financial, Westpoint, Opes Prime, Trio Capital and most recently, CBA’s advice business, have been setbacks to this progress. The watering down of FOFA is a rich source of rancour for major bank critics.

A few weeks ago, I attended a meeting where two Nobel Laureates debated why the public hates the finance industry. Then this week, David Murray’s Financial System Inquiry highlighted major shortcomings in Australian wealth management. The former CEO of CBA, who bought Colonial First State to create the largest fund manager in the country, was expected to be kind to the major banks, but he criticised the industry on many fronts. The Interim Report says in various sections:

“A trend in the wealth management sector is towards more vertical integration. Although this can provide some benefits to members of superannuation funds, the degree of cross-selling of services may reduce competitive pressures and contribute to higher costs in the sector.”

“The quality of personal advice is an ongoing problem … ASIC shadow shopping exercises indicate that consumers often receive poor-quality advice. This poor-quality advice mainly relates to two factors, the:

-

- Relatively low minimum competence requirements that apply to advisers

- Influence of conflicted remuneration arrangements

The price of personal advice has often been hidden by opaque price structures and indirect payments.”

“The operating costs of Australia’s superannuation funds are among the highest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Super System Review concluded superannuation fees were “too high”. The Grattan Institute estimates fees have consumed more than a quarter of returns since 2004.”

“It is very difficult for the superannuation system as a whole to beat the market over the long run within an asset class, although it is possible for an individual fund to do so. As Nobel Laureate William Sharpe noted:

‘Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs.’”

Far from easing the pressure on the major banks, David Murray has delivered more setbacks, especially to the legitimacy of the revisions to FOFA.

The image of financial services professionals in Australia

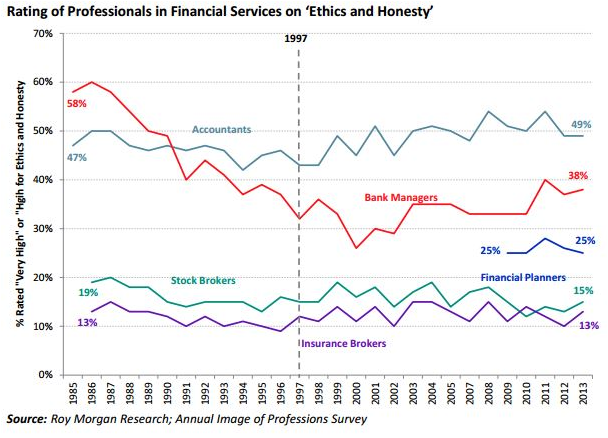

Roy Morgan Research has tracked the image of financial services professionals since 1985, and reports:

“Unfortunately, very few Australians trust professionals in the financial services industry, rating them consistently poorly for ‘ethics and honesty’. Not exactly the best foundation for a successful working relationship, is it?”

For ‘ethics and honesty’, only 25% of Australians rate financial planners as ‘very high’ or ‘high’, and it’s even worse for stockbrokers (15%) and insurance brokers (13%). The once-trusted bank manager scores only 38%, down from a healthy 58% in 1985, as shown below:

How did the Nobel Laureates explain the hatred?

At the 2014 Research Affiliates Advisory Panel at Laguna Beach in California, the first session was hosted by their Chairman, Rob Arnott, in discussion with two Nobel Laureates, Harry Markowitz and Vernon Smith. The topic was “Why Does Main Street Hate Wall Street?”, or more prosaically, “Why does the public hate us?”

Harry took it gently. He thought it was mainly a lack of education, and we need to tell the public about the importance of financial intermediation for the functioning of a market economy. But digging deeper, Vernon Smith pointed out that what Adam Smith wrote in his 1776 The Wealth of Nations is often mistakenly quoted to justify self-interested market behaviour. Adam Smith described his system of natural liberty thus:

“Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interests in his own way.”

But Vernon said this can only be understood in the context of Adam Smith’s 1759 Book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. While people have a right to be ‘self-loving’, part of their maturation is to learn rules of conduct that are ‘other-regarding’. Greed is controlled through socialisation.

“He must humble the arrogance of his self-love and bring it down to something which other men can go along with … we must become the impartial spectators of our own character and conduct.”

Vernon believes our industry is guilty of ‘crony capitalism’ based on privilege. We gamble with other people’s money, offer them returns we don’t know we can deliver, charge hefty fees, take the profits but pass the losses to the taxpayer. Rob echoed the views on cronyism. Consider the recent US bailouts of the most prestigious names on Wall Street. Politically-connected banks were protected, and within months, their executives were paying themselves massive bonuses, and it has continued since. As Chris Brightman, Chief Investment Officer at Research Affiliates, said in his summary:

“Much of our industry is a deadweight loss to society, and the public is justified in its disdain.”

Asset consultants cannot pick outperforming managers

On the second day, we heard from Tim Jenkinson of the Said Business School at the University of Oxford. His subject was, “Do Investment Consultants Pick Winners?”. Institutional investors (not uneducated retail) managing hundreds of billions of client money hire asset consultants like Mercer, Towers Watson, Russell and Cambridge Associates to help with fund manager selection. Jenkinson and his team quote statistics which show 94% of ‘plan sponsors’ employ an asset consultant. These are supposed to be ‘the smartest guys in the room’. They tell our biggest investors where to allocate their money. What is the main conclusion of the paper?

“In sum, however, the analysis finds no evidence that the recommendations of the investment consultants for these U.S. equity products enabled investors to outperform their benchmarks or generate alpha.” (Cuffelinks will write a comprehensive review of this study in a future edition).

Why do institutions bother with asset consultants when the managers they pick usually underperform? Well, it’s a ‘hand-holding service’, it protects against ‘headline risk’, and plan sponsors probably don’t even realise how inaccurate the recommendations are. Highly paid executives pay other highly paid executives to protect their backsides, without much idea whether value is being added. This process even has a name – deflection – which is the opportunity to fire someone else so that the institution or its executives are not fired. It’s perhaps the most important service that asset consultants perform.

What about the theories and the academics?

If that’s the real world of investing, what do theoretical models say about capital market prices? Brad Cornell, Professor of Financial Economics at California Institute of Technology (among many distinguished roles) told us that at best we can put a wide range around possible prices, and our models have basic flaws which render them of little practical use. Then Ivo Welch, Distinguished Professor of Finance and Economics at UCLA, said we should have little if any confidence in capital asset pricing models for predicting future returns. Yet these models play a major role in company valuations, M&A activity and defining flows of billions of dollars of capital. We use the models in business schools for capital budgeting and investment plans, but they have negligible predictive capacity. Chris Brightman again:

“Our clients and business partners pay us to be experts. They want to believe that we know more than we can. We are tempted to allow or even encourage this faith. Overconfidence is necessary for our business success ... Not only is there much we don’t know, but also some of what we know isn’t true’.

At the equivalent conference last year, I interviewed Burton Malkiel, renowned author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street. I asked him whether he feels any sense of disappointment at the state of the investment management industry. He replied:

“I think the reason we have not made much progress is that it is probably one of the most overpaid professions there is. It’s an inefficiency, with investment professionals paid regardless of the results. The real problem with us making enough progress in our industry is the misaligned incentives.”

Where does this leave us?

Notwithstanding our shortcomings, Rob Arnott said he likes to think that our industry does add value relative to what most investors would do without our ‘help’. Investors would be undiversified and would typically chase every fad and bubble that comes along. Indeed, the reason that contrarian investing often does add value is that the aforementioned lemmings are common in the marketplace, and likely always will be. It is the job of advisers and educators to encourage a longer term perspective.

In the face of the CBA’s apology for the behaviour of many of its advisers and the additional compensation payments it now faces, we might expect widespread industry remorse. However, what we actually have is a public argument about the merits of a Best Interests Duty, the definition of conflicted remuneration, the reason we don’t need opt-in for fees, and defence of the vertical integration model.

Back at Laguna Beach in California, we drank fine wine, we appreciated the art in the galleries, we ate great food from the kitchens of the luxurious Montage Hotel, and we basked in the sunshine overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Then we jetted back to our well-paid and prestigious jobs all over the world.

William J. Bernstein, author of several classic books on investing, calls us ‘talented chameleons’ that populate the financial professions. He tells his readers,

“The investment industry wants to make you poor and stupid.”

That’s why at least some of the public hates us.

Graham Hand is Editor of Cuffelinks. He was General Manager, Capital Markets at Commonwealth Bank; Deputy Treasurer of State Bank of NSW; Managing Director Treasury at NatWest Markets and General Manager, Funding & Alliances at Colonial First State. He has consulted widely across the finance industry, written for major financial journals and has had two books published.