Good Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) modelling should factor in rebalancing rules, as the rebalance benefits may be material, especially in a low-return environment. Using a simulation-based approach is sensible as it can help capture path dependencies and rebalance rules, but unfortunately it’s not implemented in practice as much as it should be.

As a result, the rebalance benefits of bonds are often ignored in formal SAA modelling and the diversification benefits are simply limited to the volatility reduction benefits only, resulting in a lower allocation to liquid defensive assets than would otherwise be the case.

Rebalancing benefits are not, however, the result of statistical anomalies or luck, but can be attributed to a unique source of risk premia (the additional return derived from accepting unique, or non-diversifiable, sources of risk).

How does Strategic Asset Allocation modelling work?

The standard approach to SAA modelling is largely as follows:

- Make your capital market assumptions, including asset class expected returns, confidence intervals and return correlations between asset classes

- Input the capital market assumptions into a mean-variance optimisation engine

- Observe the output (commonly called an 'efficient frontier'), select the appropriate efficient portfolio based on overall risk tolerance, and tweak where appropriate.

While in theory this makes sense, the way this is often applied in practice has some glaring issues, including conflating the return volatility over time with the dispersion of the future return distribution over a set horizon.

The other big flaw is applying a one-period approach to the entire SAA horizon despite the existing of rebalancing rules. Ignoring path dependency and one’s own rebalancing rules result in not appreciating that actual portfolio returns do not equal the weighted average returns of each building block in a multi-period framework.

The long-run benefits of rebalancing

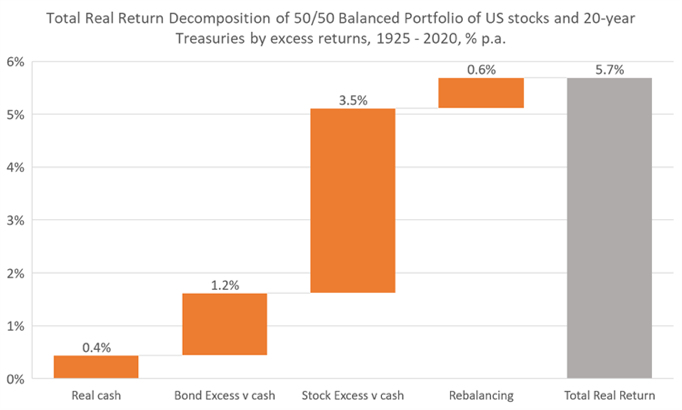

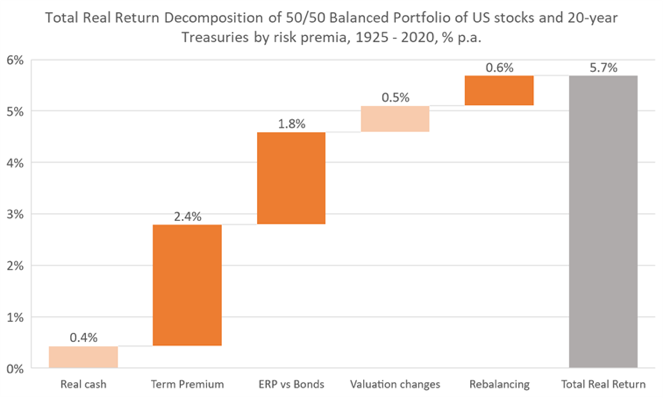

The following waterfall charts and tables demonstrate the material performance benefits rebalancing provides, using US data in 50/50 balanced portfolios of stocks and bonds from 1925 to 2020.

Chart 1 shows the total return contributions of the various building blocks to overall real returns of a balanced portfolio. In contrast, Chart 2 decomposes the contributions into risk premia, specifically:

* the term premium for duration exposures (both equities and long-term government bonds) and

* the equity risk premium (the excess returns of stocks in excess of long-term government bonds, stripping out the effects of valuation changes).

Chart 1: Real Total Return Decomposition by Asset Class Contribution

Chart 2: Real Total Return Decomposition of Balanced Portfolio by Risk Premia Contribution

Sources: Morningstar, BetaShares Capital

The ‘costs’ of chasing yield

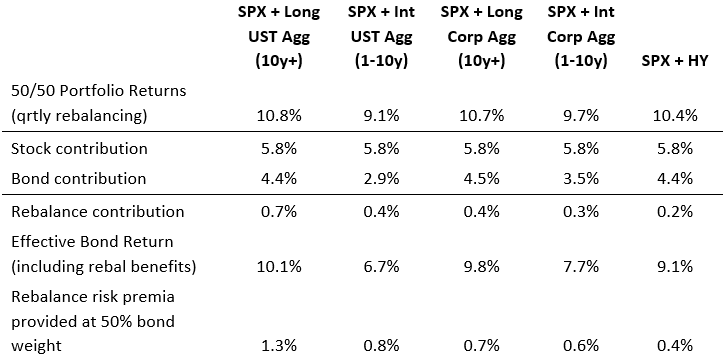

It’s important to be aware that rebalancing benefits are not equal across fixed income exposures.

Cash and government bonds generally provide the greatest rebalancing benefits, with the benefits eroding as more credit risk is taken on. This is important, as it may be tempting to replace high-grade bonds with high-yield credit on the basis of standalone expected returns. This however ignores not only the volatility and drawdown reductions of high-grade bonds, but also their rebalancing benefits in balanced portfolios.

Table 2 illustrates this using the S&P 500 (SPX) and five different fixed income indices: 10yr+ US Treasuries (“Long UST Agg”), 1-10yr US Treasuries (“Intermediate UST Agg”), 10yr+ Investment Grade (IG) corporate bonds, 1-10yr IG corporate bonds, and US high yield corporate credit (i.e. junk bonds).

For example, on a standalone basis, US high-yield credit delivered identical returns to long duration US Treasuries, but the latter provided a much higher marginal total return contribution to a balanced portfolio.

Table 2: 50/50 Balanced Portfolio, Quarterly Rebalancing, 1983-2020

Sources: Bloomberg, BetaShares Capital

Why does a rebalancing risk premium exist, and who ‘pays’ it?

There is a common belief that what matters for diversification benefits is simply correlation. This, however, is an incomplete explanation. Correlation can assist with volatility suppression, but rebalancing benefits arise from a combination of correlation, volatility (covariance), absolute return dispersion, and mean reversion in relative returns.

One interpretation is the rebalancing premium can be seen as compensation for mean-reverting rebalancing rules, which on their own expose the investor to risk of unlimited underperformance relative to not rebalancing at all (such as being on the wrong side in a heavily trending market).

The other interpretation is the rebalancing premium is compensation for providing liquidity on demand (i.e. automatically buying stocks/selling bonds during equity drawdowns) and using liquidity when the market is supplying it (selling stocks/buying bonds during a strong equity rally).

This begs the question: who is taking the other side and therefore ‘paying’ the premium to balanced portfolios?

Observation would suggest it is the type of investor who benefits from an environment of trend, momentum and growing return dispersion between asset classes (i.e. leveraged, trend and momentum based strategies). Leveraged strategies benefit from getting a magnified exposure to higher risk premium assets, but the cost is the risk of losses exceeding capital.

In order to insure against the risk of a complete wipe-out, rules around leveraged ratios are typically employed, such as periodic rebalancing to a leverage target or threshold levels. However, this insurance in the form of rebalance rules comes at a cost, with the benefits accruing to unlevered multi-asset strategies.

In one way or another, all types of leveraged strategies, whether they are leveraged ETFs, trend-following strategies, active managers taking positions against a benchmark, or discretionary retail investors trading in margin or CFD accounts, are all subject to Loan-to-Value (LVR) rules that limit downside losses, and this rules-based insurance comes at a cost. This is the whole ‘cutting losses early and letting winners run’ mantra embedded into LVR-based rules.

In conclusion, rebalancing a multi-asset portfolio takes on increased importance, not just from a volatility mitigation perspective, but as a source of risk premium that can be captured through the systematic and counter-cyclical nature of the rebalancing process.

Chamath de Silva is a Senior Portfolio Manager at BetaShares, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information only and does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. It is not a recommendation to make any investment or adopt any investment strategy. Before making an investment decision you should consider the relevant product disclosure statement ('PDS'), your circumstances and obtain financial advice. See the BetaShares website (www.betashares.com.au).

For more articles and papers from BetaShares, please click here.