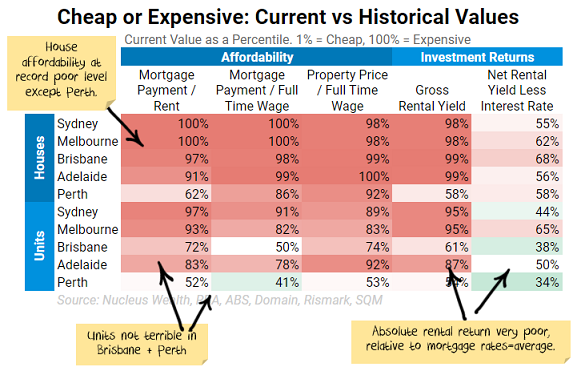

Australian property market prices are falling, and rents are rising rapidly. Interest rates are rising even faster, and affordability statistics have diverged quite sharply between houses and units. The affordability of houses is as poor as it has ever been, and while the affordability of units is below average, it is nowhere near as bad as houses. This is likely reflecting:

- a change in living preferences following the pandemic, and

- the effect of lower population growth (particularly students) over the last few years.

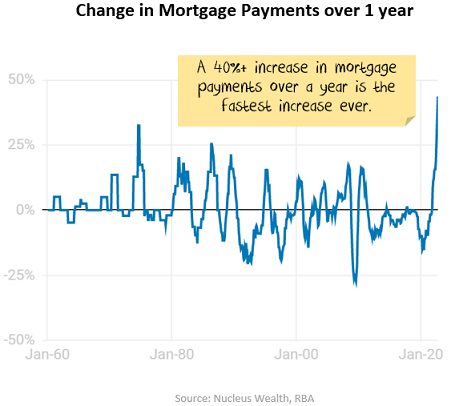

In terms of mortgage payments, a 40%+ increase in one year is higher than any other time since the 1970s. The Reserve Bank has started to express some doubt over further rate rises, but the market is expecting another 1.25%+ of rate rises.

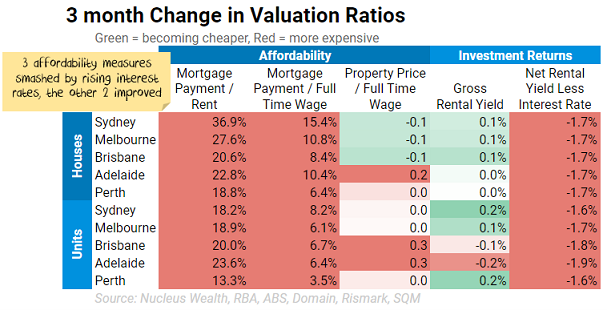

Affordability was already as poor as it had ever been in some markets before the rate rise, and housing valuation and affordability statistics worsened over September 2022. For investors, rental yields improved a little as rents rose while prices fell, but yields are still very low versus history, and interest rate rises would have swamped any gains for investors looking to borrow.

Markets are pricing in an extraordinary 7%+ mortgage rates over the next year. That would double the 2021 mortgage repayments for a 20% deposit mortgage. Given Australia has (a) the second most-indebted consumers in the world and (b) mostly variable interest rates, it seems unlikely that interest rates can rise that far without crashing the property market.

What are the limits to house prices?

Valuing the overall housing market is difficult given the rise in Australian house prices over the last 30 years, but there are limits. If house prices grow at 10% p.a. for the next 20 years, and wages/rents kept going up at their historical rates then:

- The median Sydney house price would be over $7 million.

- The median Sydney house price would be 45x higher than the median wage.

- Even if you managed to scrape together the 5% deposit (only twice the median annual pre-tax salary) to qualify for a 95% mortgage, the mortgage payment would come in at almost 3x the median pre-tax salary.

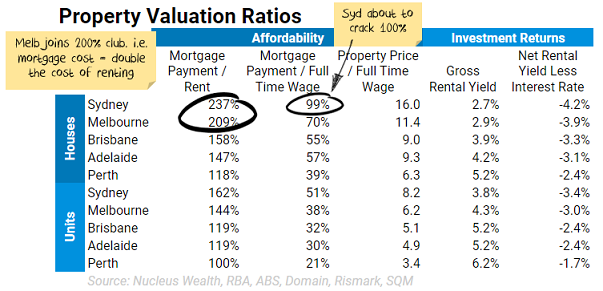

That's not a realistic vision of society to me. There are a number of key inputs into housing valuation, but interest rates are the most important. Other limiting ratios are:

- Mortgage payments to rent: comparing the cost of a mortgage with the cost of renting the same house. Using this ratio to constrain house prices, we assume that people will prefer to rent when the ratio gets high rather than buy.

- Mortgage payments to wages: assuming when the ratio gets high, people rent because they cannot afford to buy.

- Property prices to wages: assuming when the ratio gets high, people rent because they cannot save enough money to afford a deposit. We treat this as less important than the above two ratios.

- Rental yield: Rental yield is the annual rent divided by the property price. By using this ratio to forecast prices, you are assuming when the ratio gets low, investors will not buy property as they are not getting a return that is high enough.

Detailed charts for the above locations can be found in the property detail update. For more on how and why we use these ratios see our residential real estate forecasting methodology.

Waiting for the effects of rate rises

CBA economist Gareth Aird has an apt analogy of the person at the bar who has just downed five shots in a row but doesn’t feel drunk yet. The effect is coming but it is delayed.

The delay is in four parts:

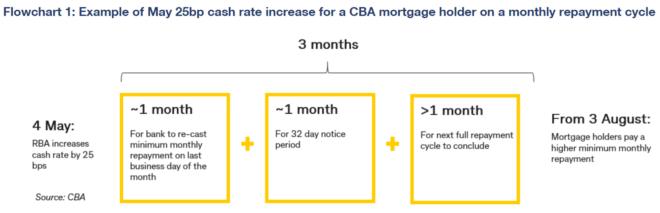

1. Delayed direct impact of rate rises. Typically rate rises take 2-3 months before affecting cash flow for a borrower. i.e. only 0.25-0.75% of recent increases have actually been felt by borrowers.

2. Delayed effect due to greater than usual concentration of fixed-rate mortgages. In March 2020, the Reserve Bank also introduced a facility where they lent directly to the banks at 0.1% for three years. This facility (and other market interventions) allowed banks to drop three-year fixed mortgages to around 2%. In response, fixed mortgages went from 10-15% of refinancing to over 40%. These will roll off, but in the interim, there are far more people who will be unaffected by the rate rises until they refinance.

3. Delayed indirect impact of rate rises. From the 3 months, for borrowers to actually notice and change spending patterns. For businesses that rely on consumer demand, it can take another few months before the effect flows through.

4. Delayed second-order and above effect. The economic multiplier compounds the effect for months going forward. i.e. consumers spend less on eating out which means that restauranteurs have less money to spend and then may lay off staff who also reduce spending. The effect of this echoes multiple times through the economy. Typical estimates suggest 1-2 years for changes in monetary policy to have the full effect.

The net impact is that the valuation ratios we have included in this report reflect the latest interest rate hikes announced by the central bank. The economic impacts, and the impact on house prices, are largely yet to come. When these factors are considered, we find that with higher interest rates, we need never-seen-before valuation ratios for house prices not to fall.

Damien Klassen is the Chief Investment Officer at Nucleus Wealth. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.