"The mechanisms for the monetization of content are in disarray." - US Cable-TV veteran James Dolan

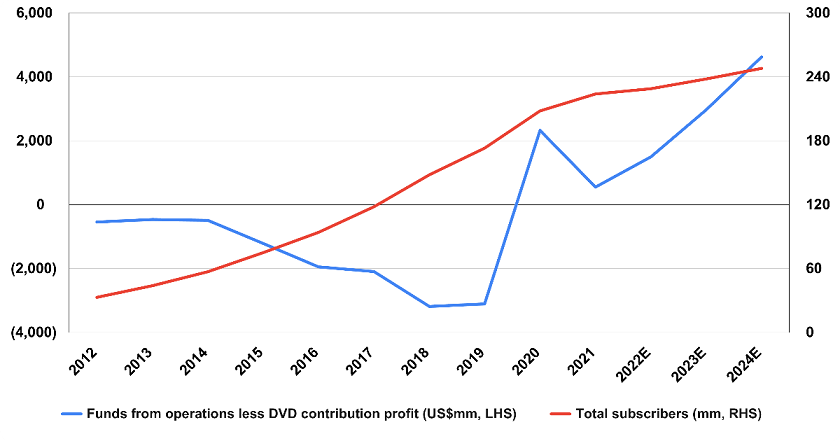

Streaming is disrupting the way TV is consumed and further changes are imminent - it is likely that all TV will be streamed within ten years. The chart below shows how Netflix only succeeded when total subscribers exceeded 175 million across the world, generating a US$5 billion turnaround to record funds from operations (excluding DVD profit) of over US$2 billion in 2020.

Netflix subscribers vs profitability

Source: Company Reports, Morgan Stanley

Netflix, irrespective of the naysayers, remains the only game in town when it comes to profitably running a streaming service. The company is not in losses, either cash or accounting, and will generate around US$11 of earnings per share this year. This is after expensing US$14 billion on movies and TV, likely the same next year. This content spending and library represent a moat which will be hard to breach. Its decision to move into advertising looks set to further underwrite profit growth.

Why Murdoch got out of movies and TV, and why Disney is struggling

Having seen Netflix succeed, permanently disrupting the business model, traditional media companies such as Disney, Paramount and Warner Bros Discovery followed. All are facing crises.

Entertainment is a scale business, so when no less an operator than Rupert Murdoch realised his film and TV business was sub-scale, he abruptly sold the company, 20th Century Fox. Murdoch had seen this film before: while attempting to build his News Corporation into a company worth US$50 billion, Google and Facebook managed to create businesses that were 10 times more valuable in a fraction of the time - at the direct expense of Murdoch’s News Corp/Fox.

Murdoch made the smartest business decision of his life and sold. Disney bought.

The merged Disney Fox last month filed a US$1.5 billion quarterly loss in its streaming service despite being over the magic 175 million subscribers, implying that something is very wrong with its cost structure. The reported results were so bad that the company fired its chief executive Bob Chapek and brought back the previous CEO Bob Iger.

As we noted of Disney’s move into its own streaming service in 2019, to generate meaningful subscriber additions and hit scale the company would first have to remove its own content from rival cable and streaming platforms. This removal would hit hard the 41% of total revenues (US$24.5 billion in 2018 out of US$59.4 billion) and 42% of total operating income (US$6.6 billion of US$15.7 billion) the company generated from these businesses at the time.

In our 2019 article we said:

“Streaming will ultimately disrupt and supplant traditional free-to-air channel viewing globally, with the emergence of four or five players, like Disney+ and HBO, along with Netflix and maybe Apple, as the new majors. But [the] buyers who pushed the Disney stock price up 30% in the three-month lead-up to the announcement won’t be the same as those who will be around to stomach the five years of grinding and significant losses the company will have to absorb, all with little clarity on the final success of the venture. For Disney, this may be a fairy tale ending, but the plot calls for some very dark times first.”

This cable-streaming balancing act is being attempted by many other large legacy players, mostly without real success. Warner Bros Discovery (owner of HBO/CNN/Time Warner and maker of Game of Thrones) which last year changed hands for the second time in two years, is also struggling to get its streaming service into the black. So is Paramount, Peacock and even AMC, a cable TV major in the US which has been around for over 50 years (and is the maker of Breaking Bad and Mad Men, among many achievements).

Below is an extract from a memo to AMC employees by its chairman explaining the problem:

“Our industry has been under pressure from growing subscriber losses primarily due to cord cutting. At the same time we have seen the rise of direct to consumer streaming apps including our own AMC+. It was our belief that cord cutting losses would be offset by gains in streaming. This has not been the case."

And then this stunning admission: “The mechanisms for the monetization of content are in disarray.”

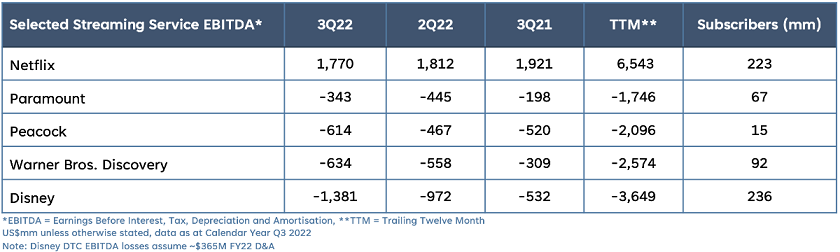

Legacy players are racking up significant streaming losses

Source: Company Reports, LightShed Partners

Disruption, incentives and cost structures

Incentives and optimised cost structures are crucial in any business, and they help explain much of the success Netflix has had in streaming to date. The company does not have to decide whether or not content goes to cable, movie theatres or streaming (or in what order). It also doesn’t have to make that choice while being held hostage by its capital structure - legacy players have a lot of debt and require linear network profits to service it.

Netflix will continue to benefit from the shift to streaming, especially as cord-cutting accelerates, and from other growth drivers like its password sharing and advertising initiatives. This will be revenue growth on top of its already profitable streaming model.

Meanwhile its competitors are still searching for a cost structure that works in streaming at the same time they experience structural declines in some of their largest and most profitable business segments (linear TV).

We don't believe the dark times are over for these legacy media players just yet.

Alex Pollak is Chief Investment Officer and Co-Founder of Loftus Peak. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual. Loftus Peak Global Disruption Fund (ASX:LPGD) is available to investors on the ASX as an active Exchange Traded Managed Fund.