In Australia, the Commonwealth Government was carrying very low debt levels of $50 billion before the GFC. Then, to counter the GFC, it borrowed an average of $50 billion per year net for the next 10 years, taking the level of debt to $560 billion before the virus hit. Now it is borrowing around $35 billion per month to fund all of its welfare programmes.

Can we afford all this debt?

The Commonwealth Government ran surpluses for six years from 2003 to 2008 in the China-driven mining boom, then it ran deficits in the GFC to support economic growth and jobs. That is precisely what governments should do - build surpluses in the good years so they can deficit-spend in economic crises to provide short-term support.

The problem was that both Labor and Liberal/National governments since the GFC became addicted to big spending and running up deficits well beyond the GFC. The Commonwealth ran deficits for the next nine years until 2018, for what was really just a one-year crisis, especially as the Chinese stimulus re-boot boosted exports, revenues and jobs from 2010 on. Windfall iron ore revenues produced a tiny surplus in the June 2019 year, but Commonwealth debt had grown from $101 billion (8% of GDP) in the GFC in 2009 to $540 billion (28% of GDP) in 2019.

The size of government has been increasing over time as a share of total national spending. In 2007, at the top of the last boom prior to the GFC, Commonwealth spending was $224 billion (21% of GDP), but by 2019 before the virus, it had grown to $448 billion (25% GDP). During that time the debt pile grew by 830%, but the population grew by just 20%, and CPI inflation had only risen by 30% in total. Then the virus (or rather the virus lockdowns) hit, and the government is now borrowing $30 billion-$50 billion per month to fund its spending programs. This seems high, but is it?

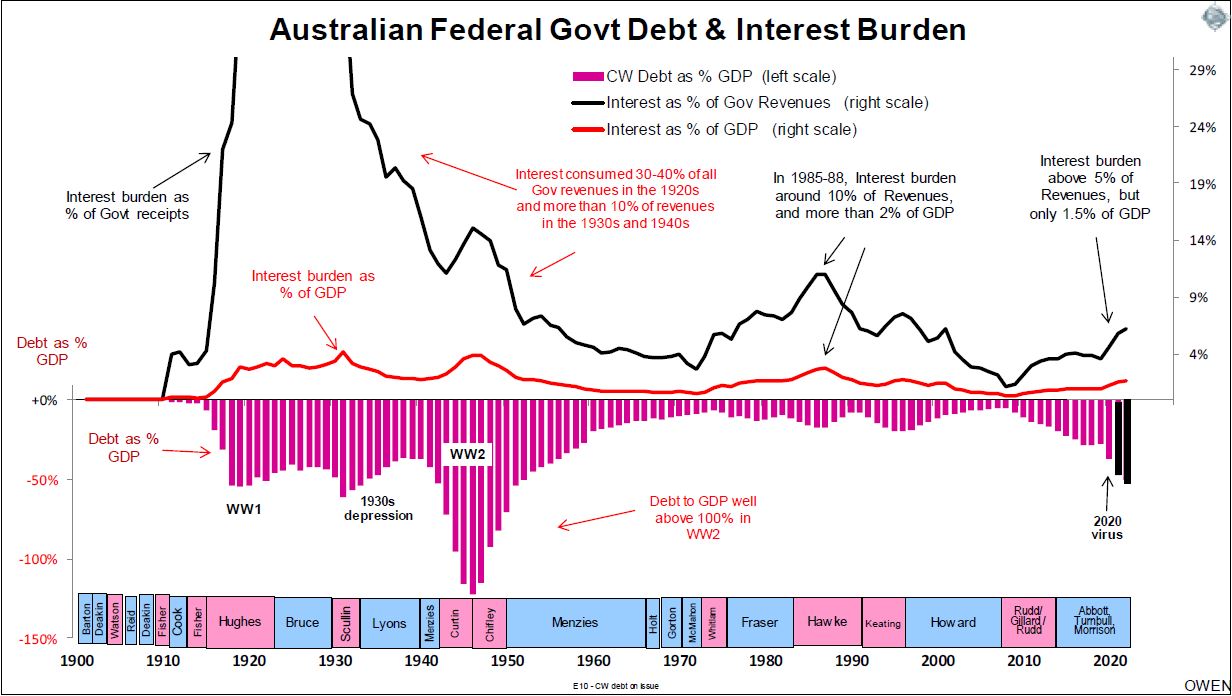

To provide some context on the national debt, the chart shows Commonwealth Government debt, and the debt servicing costs since Federation. The pink bars in the lower section show debt as a percentage of national output (GDP) each year.

Recent debt build-up and affordability

Toward the right end of the pink bars, we see the build-up of debt from 2009 on. The two black bars represent likely 2021 and 2022 debt levels assuming the current plan to increase debts by $240 billion in the current June 2021 year, plus an additional say $100 billion in the June 2022 year. Welfare is extremely difficult to scale back or withdraw (eg the JobSeeker will probably remain at the higher level) and it doesn’t include the government promises of tax cuts.

The current level of debt at 37% of GDP is higher than it has ever been since 1956, but still lower than historical average debt levels. The likely 2021 and 2022 levels of debt are also still low relative to the previous big debt build-ups.

Australia’s current level of government debt is low relative to most of our global peers, and even the 2021 and 2022 levels would be low in global terms. But more important than the level of the debt is its affordability.

The current $684 billion of debt costs taxpayers $22 billion per year in interest, or $61 million every day, or $2.40 per person per day (less than one coffee per day per person). The total interest burden sounds like a lot but there is more to the story.

The affordability of the debt is shown in the upper section of the chart. Interest on government debt as a percentage of national income (GDP) (red line), and also the percentage of government revenues (black line). The current interest burden is quite modest, at 4.5% of government revenues and just 1.2% of national income.

This is lower than almost any other time since the early 1950s, and also lower than almost every other country in the world today. Even the likely 2021 and 2022 debt levels would see the interest burden at around 5% of government revenues and 1.5% of total national income.

The reason for the relatively low interest burden is that the interest rates on government bonds are at historical all-time lows thanks to declining global bond yields since the GFC, and the RBA pegs and bond-buying since the virus crisis.

Low rates will not last forever

Bond yields will probably rise in the medium term as economic activity recovers here and around the world. The good news is that rising bond yields don’t translate into higher interest payments until each bond matures in the future and is refinanced by another bond at a higher prevailing rate at that time, which in some cases is 30 years into the future.

Even if bond yields rise rapidly in the next few years, the average interest cost on the total pile of debt will remain low for at least another decade because of the low rates already locked in.

If Australia were a company, its national debt would be labelled a ‘lazy balance sheet’ and the CEO and Chairman would be fired by shareholders for not borrowing enough to invest in productive assets for future growth.

Based on affordability, these levels of debt are manageable but there is one major caveat. Investing for the long-term future requires coherent vision, long-term commitment and a willingness to make tough decisions. These require longer election cycles than the current theoretical three-year terms (which never last the full three years), and recently have been punctuated by ‘palace coups’ within the ruling parties between elections.

With that caveat in mind, Australia’s position is one of the best in the world. It has always been a country in which the opportunities for growth and investment have far exceeded the local savings pool available to fund its development, and so it has always had to import people and capital.

A country is not a household

When talking about debt, many people liken a country to a household, where it is prudent to have no debt, or at least to pay off debts as quickly as possible. In a household, the breadwinner(s) stop generating income at some point and thereafter must draw down their accumulated savings to fund decades of retirement spending with no labour income.

However, a country is more like a company than a household. Companies and countries can last forever (in theory anyway) and they can (and probably should) carry a level of debt, as long as the cost of debt is lower than the additional income generated by the productive assets funded by the debt. Ideally, the debt should be in the country’s own currency (as is 100% of Australia’s debt), and should mainly be fixed-rate, not floating, so the level of interest payments is not volatile (this is also true for Australia).

Most countries lie somewhere between these two views. Australia has an aging population and rising welfare and health costs, but it is still the best placed among its ‘developed’ country peers due to its relatively favourable demographics and healthy immigration programmes targeting work-ready individuals and families.

It is far better placed than Japan and northern Europe that have declining populations, declining workforces and declining tax-payer bases. Those countries are indeed more like households, where the breadwinners in aggregate are reducing their income-generating ability and are literally dying off.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.