This article is an edited transcript of Justin Halliwell’s segment in Schroders’ recent broadcast “What happens when concentration cracks?”

We talk a lot about the asymmetric risk associated with M&A [mergers and acquisitions] with all companies. We have seen a lot of value destruction from M&A over time and miners have been very much at the forefront of that issue. BHP’s failed bid for Anglo American feels like they escaped, like they were saved from themselves.

The miners have extremely privileged assets. They generate amazing cash flow and really their key job is to allocate that efficiently. We really felt with the Anglo bid that was not the case, and I can put a few numbers around that.

It was a complicated transaction with Anglo owning a lot of assets which everyone will have slightly differing views on regarding value, but really all BHP wanted was the copper. And our numbers showed they were paying about $30 billion for the copper assets, which is about $50,000 a ton of copper production.

That's around triple the typical greenfield cost of late. And in fact, one of Anglo’s copper assets they would have been acquiring was a greenfield just completed. So for a brand-new asset, they were going to pay triple what was paid for the building of that asset.

The important part there is that, I mean, that's probably a good asset. It's probably going to generate 15%, 20% returns on that recent capital investment. For BHP to make that kind of return, which is what they're looking for on the acquisition, we're looking for implicit returns north of 50% on that asset. That's just not feasible.

Even if the asset is good enough and copper prices are high enough, we'd expect governments to want to take more and more of that profitability. So, we just think it's a one-way risk in terms of that transaction. Now, like I said, they were saved from themselves. They've gone into a smaller asset in copper with less scope to destroy value.

On the flip side, they're also selling assets. So, they've been getting rid of what they consider poorer-quality assets, such as in the coal space where there are less buyers. And you can see the Whitehaven transaction, you kind of feel like Whitehaven has done well out of that one. So, BHP should just stick to their knitting, generate cashflow and allocate it more efficiently.

Future facing metals still small fry in Australia

Copper is important for electrification and decarbonisation, and lithium obviously gets a big play in that as well. BHP are very bullish on copper, there's no question, and that was a big driver behind the Anglo transaction. But the numbers are small still - even within copper, which is obviously a far more developed commodity than something like lithium.

If you look at Australia specifically, the numbers in 2023 in terms of export value were something like $90 billion of iron ore, $60 billion of coal and $5 billion of copper. And lithium, with an incredibly strong price, was about $10 billion.

So $15 billion for the future facing materials, which is what the companies like to call them, versus $150 billion for the dull and boring iron ore and coal. So, we're a long way from those green and future facing commodities, certainly in Australia, from overtaking the more mature commodities.

Now it's probably worth reflecting on something like lithium, and it really comes to how we look at commodities and how volatile commodities have become. There's a lot of money washing around the system, trying to find a home in commodities. What we're trying to do, like with lithium, is avoid the storytelling that comes with some of these commodities.

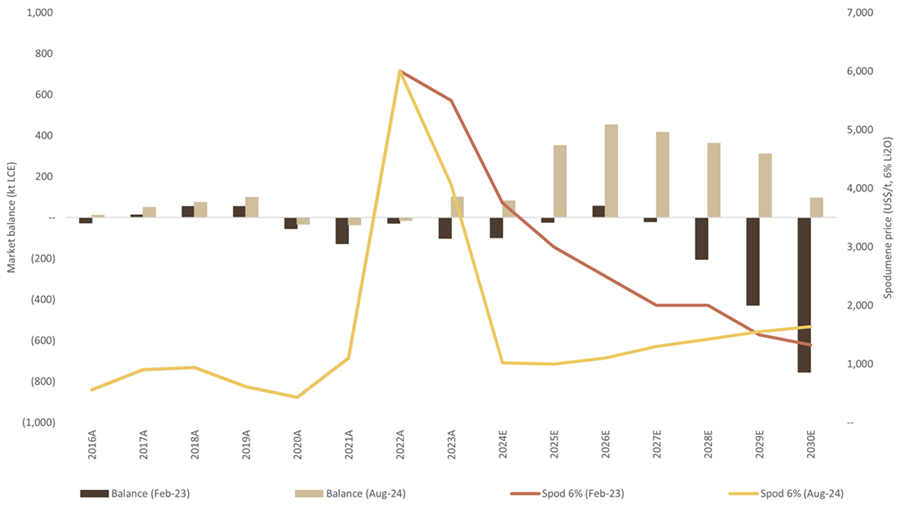

So, this is a chart from UBS. It's not to pick on them. But what we can see here is the bars on the chart are the forecast of the market surplus or deficit.

Editor’s note: the forecast from 18 months previous is shown in the dark bars and predicts a significant deficit. The lighter bars show the surplus that is now being forecast by the same broker for the same periods in the future.

It's been a huge turnaround. The lithium price has gone from a peak of $8,000 a ton 18 months ago to now sitting at $700 a ton. I mean it's a huge, huge fall. Like nothing that we've ever seen in commodity land. And as that's happened, the market and the consultants have started to change their forecast dramatically.

It's also a commodity acting like all commodities do when there's high prices. Guess what? Supply comes in that no one dreamt of. 18 months ago, it was a race for forecasting electric vehicle penetrations. As the prices of those vehicles have risen, in part due to the commodity inflation, consumers have become more focused on the price of those cars, demand started to fall a bit and at the same time, supplies come in.

What we're trying to do is we're trying to look through those cycles. We try not to get caught up in the hubris when things are very bullish, but also, we're not trying to get too bearish at the bottom. The flip of that would be something like alumina, where 12 or 18 months ago, everyone was super bearish and the price was maybe $300 a ton. Few people were making money and guess what? Supply starts to get shut down, demand stays robust and the price flips around.

So, that's what we're trying to do. We're trying to look through cycles, trying to not get too caught up in the ups and downs and try and keep a steadier view.

Justin Halliwell is Head of Research for Australian Equities at Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This extract was taken from a recent Schroders webinar titled “What Happens When Concentration Cracks?”. You can view the full webinar and selected highlights from it here.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.