The Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) reforms are designed to improve outcomes for superannuants, which is nearly all of us. The reform package is undoubtedly well-intended. Therefore it is critical that it achieves its intended purpose. This has been our focus when we have reviewed one of the most important reform measures, an investment performance test.

Unfortunately, our research (open to anyone, available here) finds that the performance test will not effectively achieve its intentions and will generate some undesirable outcomes. Statistically, the performance test will struggle to distinguish ‘good’ funds from ‘bad’. Further, the performance test will significantly constrain the investment strategies of super funds, to such a degree that the opportunity cost of the constraints may exceed the projected benefits of the YFYS reforms.

The YFYS performance test explained

The YFYS performance test assesses past investment performance. For background, super funds have two primary functions when managing portfolios:

- They choose the mix of assets (we call this asset allocation); and

- They implement their asset allocation (implementation), sometimes by investing directly and sometimes via external asset managers, who charge fees.

The YFYS performance test ignores asset allocation (which has a large impact on performance) and only assesses implementation performance. It does this by mapping portfolio exposures to a limited set of public market indices.

The example below places context around the total performance outcome. Fund A outperforms Fund B because it chose a better performing asset allocation, which more than offsets its weaker implementation performance. Yet Fund A will fail the YFYS performance test.

|

Performance component

|

Fund A

|

Fund B

|

|

Asset allocation

|

7.5%

|

6.5%

|

|

Implementation

|

-0.5% pa

|

0% pa

|

|

Total performance

|

7.0% pa

|

6.5% pa

|

Will the test be able to effectively distinguish between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ performers?

Performance varies over time. A fund may have strong capability and is expected to perform well over time, but variability exists and there is a chance they will fail the performance test at some point in time. Similarly there is a chance, again due to variability, that a fund with poor processes will pass a performance test. Greater variability takes the likelihood of failure towards 50%, akin to a coin toss. Longer timeframes smooth out the impact of variability.

The statistically-minded may recognise these scenarios as type I (identifying a ‘good’ fund as poor) and type II (identifying a ‘poor’ fund as good) errors. These essentially reflect the statistical effectiveness of the test. An effective test will have low likelihoods of both errors occurring.

We found that two design characteristics of the YFYS performance impair its effectiveness.

The first, as previously explained, is that the test ignores asset allocation performance, which can create large variability in fund performance.

The second is the benchmarking approach. There are many assets which are not benchmarked accurately, most notably private equity, unlisted property, unlisted infrastructure, all forms of credit, inflation-linked bonds, and the entire universe of alternative assets. This creates significant variability in the performance test results.

The good news is that for funds with extremely poor implementation performance the YFYS performance test will be quite effective. The bad news is that in less extreme situations, the ones more likely to be faced in the future, the test won’t work well.

Calibrated to realistic future scenarios our research revealed that the likelihood of the YFYS performance test mistakenly identifying a ‘good’ fund as poor was 35%, and the likelihood of mistakenly identifying a ‘poor’ fund as good was 42% (full results here).

Consumers deserve an effective performance test and industry deserves a fair assessment. As it stands the YFYS performance test won’t provide either.

Will the test constrain super funds from achieving best outcomes?

For super funds, the penalties of failing the performance test are severe. Accordingly, we expect them to actively manage their portfolios to ensure a high likelihood of passing the test.

This means reducing variability to the performance benchmark (this variability is known in industry as 'tracking error'). In turn this means limiting exposure to all those above-mentioned assets which the test doesn’t benchmark accurately (we found it would take over 50 indices to create a reasonably effective implementation test).

If present investment strategies are maintained, funds may find they have to frequently adjust their portfolios in reaction to short-term underperformance, which could incur sizable transaction costs.

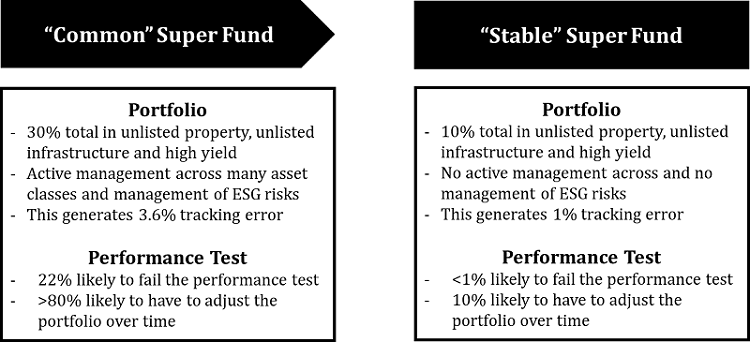

In future, super funds will seek a stable investment strategy which provides a high likelihood of passing the performance test and low likelihood of having to frequently alter their portfolios.

How much would portfolios have to be shifted from current state, which is focused on member best outcomes, to future state, where they need to account for the performance test? This effectively represents the constraints imposed by the performance test. The diagram below presents the conflict faced by super funds.

Using conservative estimates (here) we calculated the opportunity cost of the portfolio constraints implied by the YFYS performance test. In aggregate we estimate these will exceed $3 billion per annum, greater than the projected benefits of the YFYS reforms in total ($17.9 billion over 10 years).

Can we design a better YFYS performance test?

A well-designed performance test can benefit consumers. Our research, which combined academic techniques with industry experience, has identified flaws in the performance test which will cost consumers. We believe the test can be modified in a simple manner by including an additional metric which focuses on risk-adjusted returns. This would remove many of the shortcomings and provide consumers the protection they need and deserve.

David Bell is Executive Director of The Conexus Institute, a not-for-profit research institution focused on improving retirement outcomes for Australians. This article does not constitute financial advice.