Does a fish know it’s swimming in water? Probably not until it’s no longer submerged. This illustrates that it can be difficult to know — never mind understand — the paradigm you’re living in until there is an abrupt change.

The water we used to swim in

Interest rates are the reward for savers foregoing the ability to consume in the present. Since all economic and financial activity takes place across time, the world requires positive rates. Without positive interest rates, market signals in the economy and financial markets become distorted. All projects are funded, asset values inflate and capital is misallocated.

In the 2010s, the economic and financial market waters were comprised of suppressed rates that, at some points, reached the zero-bound and into negative territory. Financial markets swam in waters comprised of extraordinary returns, below normal volatility and lower than average correlation and thus historically good Sharpe ratios.

Until 2022, when the water (or paradigm) shifted.

Three decades versus three centuries

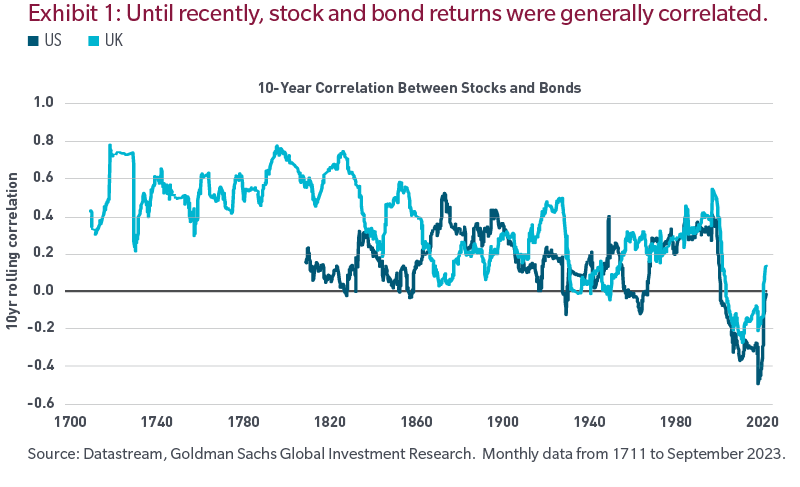

Still reeling from the interest rate shock of 2022, investors have been forced to confront what looks like an anomaly: the positive correlation between stocks and bonds.

However, the painful reality is that 2022 wasn’t so anomalous when viewed through a long-term prism. It was an example of the dangers of allowing the recent past to obscure protracted historical patterns. The water, or paradigm, is merely shifting back to its natural form as the hurdle rate for all investments, interest rates, has begun its normalization process.

In a November 2021 piece titled Respecting Three Centuries of Correlation, we highlighted the positive long-term correlation between nominal stock and bond returns and warned that recent decades of negative correlation were unsustainable. The historic correlation is illustrated below, going back three centuries in the United Kingdom and two in the United States.

Long-term positive correlation explained

Like the fish in the parable, this comes as a surprise to many today because it’s not what their experience has taught them. And it’s not what is taught in business schools (but should be).

Taking a step back, investors bunch varying investments into labels such as stocks and bonds, public and private debt, growth and value equities, etc. While these distinctions are important, material and worthwhile, what often gets lost is that they all ultimately rely on the hope or promise of cash flows.

Every investment requires a commitment of capital from a saver in exchange for future returns that compensates them for not only the commitment of time but also the risk that the project may fail. When viewing sub-asset classes in this way, there is one asset class: cash flows. The more predictable or stable the future cash flows, the lower the volatility that asset should exhibit relative to assets with greater time commitment and cash flow risk. This is where the benefits of diversification normally come from: a portfolio whose sources of returns (i.e., future cash flows) are diversified across time and risk levels.

While there have been and will remain diversification benefits between equities and fixed income securities, those benefits have been overstated in recent decades due to low inflation and artificially suppressed interest rates. Investors who were allocated across stocks and bonds not only enjoyed outsized returns with abnormally low volatility, but also uniquely high risk-adjusted returns, in part due to this negative but unsustainable negative covariance.

Why is this important?

The inflation and interest rate shock of 2022 has changed the water.

While we can’t predict the terminal value of real interest rates, we’re certainly closer to a more normal rate environment than before, which would imply a normalization of the long-run stock/bond relationship. Investors who have targeted future Sharpe or information ratios based on the recent past may be set up for underperformance.

What can we do?

As time passes, areas where capital was misallocated will be exposed. For instance, projects and cash flows that were a function of financial gearing will crumble under the weight of high debt burdens and bad projects will need to be recapitalized.

While correlations of asset classes such as stocks and bonds normalize, the importance of security selection and manager allocation will matter immensely, as these not only become drivers of return but also larger drivers of covariance and portfolio diversity.

Conclusion

As a famous investor once said, price is what you pay, but value is what you get.

In our view, while prices are high, the value of some financial assets is too low. The paradigm of suppressed capital costs and low labour expense has changed. There will be fish that will, at best, fall down the food chain and others that, at worst, get eaten. Conversely, the fish with the ability to deliver cash flows to investors that are less dependent on the prior regime may become scarce assets, and why we think the type of fish you have in your portfolio will be what matters in this new, but old, paradigm.

Robert M. Almeida is a Global Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager at MFS Investment Management. This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. Comments, opinions and analysis are rendered as of the date given and may change without notice due to market conditions and other factors. This article is issued in Australia by MFS International Australia Pty Ltd (ABN 68 607 579 537, AFSL 485343), a sponsor of Firstlinks.

For more articles and papers from MFS, please click here.

Unless otherwise indicated, logos and product and service names are trademarks of MFS® and its affiliates and may be registered in certain countries.