“The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.”

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776

Everyone has a different idea of which taxes are fair. The ‘father of modern economics’, Adam Smith, thought tax should be paid according to what a taxpayer could afford. Without wading through an ethical debate, let’s focus mainly on one way Australia raises money to finance the operation of government: the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on investments.

The realised gains on investments, which are what a CGT taxes, should fall within a comprehensive definition of income.

What is the logic of giving a generous 50% discount on CGT for assets held greater than 12 months, when other income is taxed at marginal personal rates? This has the knock-on effect of encouraging people to arrange their affairs to generate a CGT rather than income.

The current favourable treatment of CGT has become sacred ground, defended again recently by Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, as if it were a basic and long-standing tenet of our budget system.

The large discounts of today were only introduced in 1999, when market circumstances were different. It’s time to recognise that after 18 glorious years of CGT heaven, it is no longer appropriate.

[Register for our free weekly newsletter and receive the free ebook, Cuffelinks Showcase 2016]

Register

Look what’s happening in the current residential market

In a comprehensive study of CGT (in Economic Roundup, Issue 2, 2014), John Clark of the Tax Analysis Division of the Australian Treasury, wrote:

“The concessionary treatment of capital gains income is arguably the primary motivation for financial investment in negatively geared real estate, which aims to shift all of the investment return into the capital gain on the eventual sale of the asset.”

Only the hard-hearted would feel no sympathy for young families struggling to take the first step into their own home. A home is usually more than an investment. It represents a more secure future and roots into a community and lifestyle. Home ownership is part of our culture. Australia’s short-term rental leases make a precarious existence for tenants who are often uprooted with a few weeks’ notice. With both Sydney and Melbourne experiencing auction clearance rates over 80%, and last month CoreLogic claiming Sydney house prices hit an annual growth of 18.4%, frustration levels show no sign of easing.

What pushes the disappointment to anger for first home buyers is knowing they were beaten at auction by a property investor at a different stage of life, probably buying a second or third property, with confidence buoyed by tax breaks.

(Victoria has announced a range of measures to help first home buyers, such as a waiving of stamp duty and a Vancouver-style tax on empty properties at 1% of the capital value. The fear is that these will merely stimulate demand further in the residential market, while doing little to curb the enthusiasm of investors).

Briefly, what are the tax breaks?

Without going into great detail, the two main tax breaks that fuel investor property appetite are:

- Capital Gains Tax discount

Assets acquired since 20 September 1985 are subject to CGT unless specifically excluded, such as personal assets. A capital gain is the difference between the cost of the asset and the amount received on disposal. The realised gain forms part of taxable income in the year of sale. A loss can’t be claimed against other income but it can offset a capital gain and can be carried forward.

For assets held for 12 months or longer before the CGT event, there is a 50% discount for individuals and trusts, and a 33 1/3% discount for complying super funds. There is no CGT payable on a person’s main residence upon sale.

- Negative gearing

Where the rental income on a property is less than the interest and other expenses, the loss can reduce the investor’s taxable income (of course, the same applies in other investments including shares). Many people seem to believe that anything that reduces their tax bill is good. They talk about negative gearing as if it is an end in itself, when all it does is reduce the size of the loss. It’s still a loss.

An owner occupier who buys a family home does not have negative gearing, and mortgage payments are not tax deductible.

Why did we introduce such a generous CGT discount?

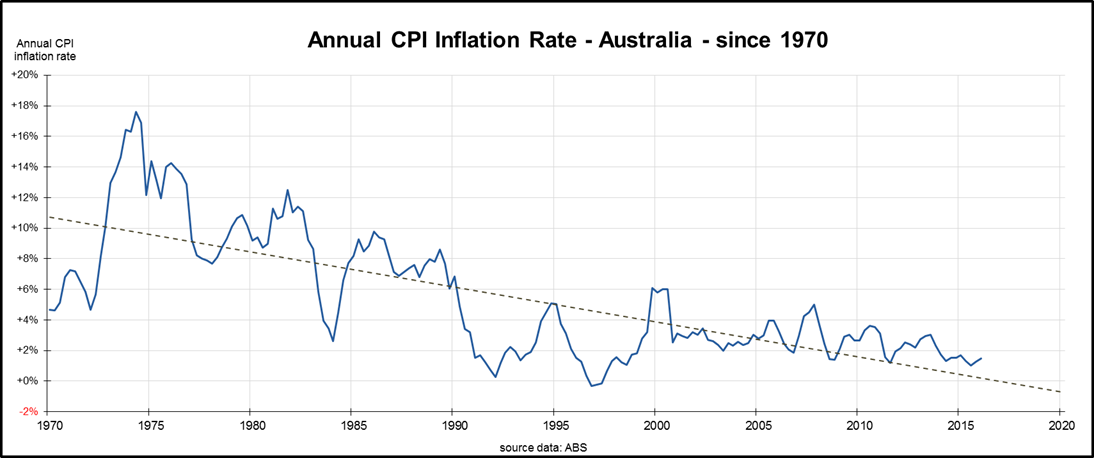

When the Hawke Keating Government introduced CGT in 1985, the rules allowed for the cost base of assets held for one year or more to be indexed by inflation when working out the gain. That is, the part of the realised gain due to the consumer price index (CPI) rises was not taxed. The 50% discount was introduced in 1999 by the Howard Costello Government. Let’s consider Australia’s inflation since 1970, as shown below.

CGT indexation

For much of the late 1980s, inflation was around 8%, and then in ‘the recession we had to have’ in 1991, it fell significantly and then rose again. By 1999, it was approaching 6%. It is now closer to 2%.

According to a paper from the Tax and Transfer Policy Institute of the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, “Somewhat surprisingly, the 50% CGT discount was introduced with little in the way of empirical evidence or modelling of the possible revenue effects.” One stated rationale for change was the old indexation method was too complicated to calculate, adding uncertainty and inefficiency to the tax system.

The rationale for returning to indexation

Economists like to measure purchasing power in ‘real’ terms, adjusted for inflation. GDP, for example, is best judged as ‘real GDP’ to determine actual economic growth. Realised capital gains should be considered in real terms, allowing for inflation over the holding period.

With inflation closer to 2%, and likely to stay low for many years, the 50% discount is extremely generous for assets realised after a relatively short period. The 50% discount is inherently arbitrary – what does 50% signify other than half? It does not appeal to the basic tenet of adjusting gains for inflation, it simply applies a number with no relationship to real returns or the length of time an asset is held (beyond the one year).

The CGT discount offends the principles of both vertical and horizontal equity, the very reasons to have a CGT in the first place. For example, a person in the top marginal tax bracket with a $1 million realised property gain will lose less than a quarter of the proceeds in tax, but would lose half in tax on other income. This breaks the principle of horizontal equity between gains. Also, as capital gains accrue to the highest income earners, it offends principles of vertical equity and the ability to pay according to our means in our progressive system. The CGT discount effectively lowers the marginal tax rate for high income earners.

Furthermore, the CGT discount pushes investment towards shares and property and away from regular income streams, such as from bonds.

As for the complexity identified in 1999, our improved accounting systems and ability to make adjustments ensure indexation is a straightforward calculation based on published statistics.

When CGT indexing was introduced, inflation was high at around 8%, and an asset held for say six years would have a 50% ‘discount’. Now inflation is around 2%, the 50% discount is inequitable.

Unlike some schemes designed to improve home ownership which simply act to increase the amount a first home buyer can afford to pay and therefore bid up prices, this CGT change would reduce investor demand and remove a speculative element from the market.

Although at high rates of inflation, it’s possible that an indexation system would be more favourable to investors than the 50% tax break, this is highly unlikely for many years.

Let’s remove this investor tax incentive and give our children a chance

There is no justification that someone can flip a property after a year and be taxed on only half the realised capital gain.

It’s also likely that knowing gains will be halved drives investor confidence, far more than the uncertain principle of ‘adjusted for inflation’. Most people will know that inflation over say five years is likely to be only about 10%, leaving 90% of the realised gain to be added to taxable income.

The capital gain discount regime which replaced the previous inflation indexed method is inherently arbitrary and has differing consequences depending on the rate of inflation and the length of time for which an asset subject to CGT is held. Let’s fix the calculations and level the playing field a little more!

(Note, there is a follow up discussion in the following week between Noel Whittaker and Chris, including extra background data).

Chris Cuffe is co-founder of Cuffelinks; Portfolio Manager of the charitable trust Third Link Growth Fund; Chairman of UniSuper; and Chairman of Australian Philanthropic Services. The views expressed are his own.