This article follows on from Gerald Stack’s excellent article for Cuffelinks comparing listed and unlisted infrastructure, and looks at the choice between investing in the equity or debt part of the capital structure.

Investors in infrastructure are generally seeking:

- returns driven by the underlying long term cash flows (ie yield-focussed rather than growth-focussed returns)

- capital stability

- some degree of inflation protection or inflation linkage. Typically underlying revenues of infrastructure assets are linked to inflation and, hence, infrastructure assets offer the prospect of inflation protection.

By definition, equity and debt sum to the value of the asset (or equivalently, the value of equity is the value of the asset minus the value of debt). This means that the characteristics of underlying infrastructure businesses feed through to the characteristics of infrastructure debt and equity investments.

Infrastructure equity:

- receives a disproportionate share of the upside in performance of the underlying infrastructure business

- is more impacted by adverse developments through the impact of leverage

- must consider the cost and availability of debt finance - during the GFC many of the sharp falls in infrastructure share prices were driven by this factor, rather than by declines in the operating cash flows of their underlying businesses

- benefits from control and directly or indirectly is responsible for the management of the asset.

Infrastructure debt:

- has lower returns (on average) and doesn’t participate in the upside of underlying infrastructure asset

- is much less risky (see below)

- is a shorter term investment – with terms to maturity typically 3-7 years. In contrast, infrastructure equity is a very long term investment as assets are usually valued based on cash flow models that go for more than 30 years

- doesn’t necessarily benefit from the same inflation protection as the underlying asset – particularly in the case of fixed rate bonds. However, many projects issue floating rate debt where interest payments move with bank bill rates (a rise in inflation would be expected to flow through to higher bank bill rates) or inflation-linked bonds (where interest and principal payments are directly linked to CPI).

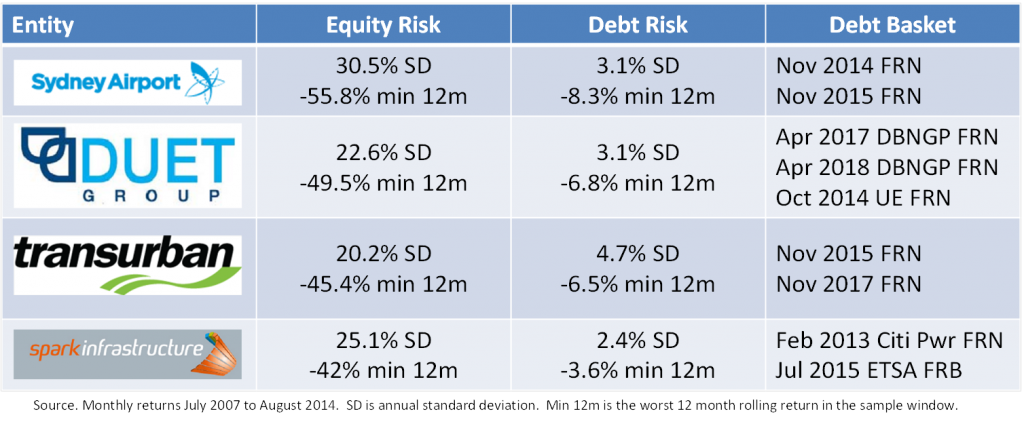

There are lots of different ways to think about risk. But one way of comparing the risk of infrastructure debt and equity is to look at the performance of listed infrastructure stocks that had floating rate bonds on issue through the GFC. While this is a small sample, only four assets, during severe market disruption, it does allow the comparison of risk outcomes between debt and equity in the same underlying asset.

Depending on whether you focus on standard deviation or worst 12 month return, this analysis argues that senior floating rate debt is 4-10 times less risky than equity in the same asset. Of course, this comes with a return trade off.

Just as infrastructure equity has listed and unlisted forms of investment, different types of infrastructure debt (loans versus publicly-traded bonds) have differing levels of liquidity and, hence, illiquidity premia.

Which is the better investment? Ultimately that depends on relative pricing and risk-adjusted returns, as well as the time horizon and risk appetite of investors. However, many investors tend to think purely of infrastructure equity when considering infrastructure investments and it may be worth thinking more broadly.

Alexander Austin is Chief Executive Officer of Infradebt. Infradebt is a specialist infrastructure debt fund manager. This article provides general information and does not constitute personal advice.