When we talk about returns from ‘Australian shares’ or the ‘Australian stock market’, what do we actually mean? Australian stock markets have always consisted of a small number of ‘investment grade’ companies with real businesses, but the vast majority of companies are, and have always been, high risk speculative gambles.

They are little more than a way for promoters and brokers to harvest money from the pockets of the seemingly never-ending waves of newly-minted speculators hoping to hit the jackpot, much like a casino.

37,000 companies tried, only 580 still listed and profitable

The chances of finding a winner on stock exchanges in Australia has been around 1%. Not a 1% chance of beating the overall ‘market index’. I mean 1% just managing to survive and build a profitable business. Here’s why.

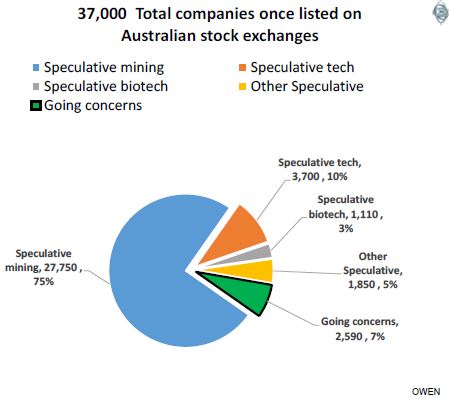

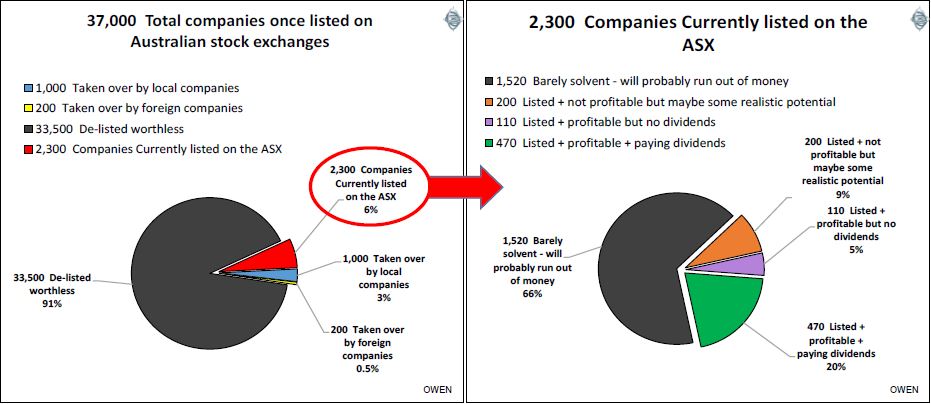

I estimate that there have been about 37,000 companies that have raised money from investors and listed on one or more of Australia’s stock exchanges at some time since the early 1800s. Today, there are only 2,300 companies left still listed on the ASX (6% of the total ever listed) and only 580 of those make any money. So what happened to the rest of them, and what happened to investors’ money?

Note: The numbers are the author’s estimates based on a study of dozens of exchanges.

In addition to the above, at least 3,000 Australian companies listed on the London market to harvest money from gullible Brits. Their success rate has been even lower.

The national ‘Australian Securities Exchange’ (ASX) is an amalgamation of the stock exchanges of Sydney, Melbourne (which once had four exchanges), Adelaide, Perth, Brisbane and Hobart in 1979. In addition there have also been several other thriving exchanges over time – mainly in mining booms – including Bendigo, Ballarat, Kalgoorlie, Charters Towers, Newcastle, and more. Each of the stock exchanges was owned by separate groups of brokers, all frantically finding and listing companies to attract money from over-eager investors in the boom years.

How do most companies disappear from the exchange?

I estimate that at least 75% of all companies ever listed in Australia were speculative mining ventures. The vast majority of these raised money quickly in the mining boom of the day and then disappeared worthless. The money taken from investors was pocketed by the promoters or exhausted looking for riches that were never discovered in profitable quantities. The most famous mining bubble stock was Poseidon in the late 1960s nickel boom. It did indeed discover a large nickel reserve in WA but it ran out of money trying to exploit it. Most mining explorers find nothing.

Another 6,500 or so companies were other non-mining speculative ventures, including tech stocks, biotech or other ventures in all sorts of other industries. (By ‘speculative’ I mean no profits or dividends).

That leaves only around 7% of companies that have listed over the years, or around 2,500 companies, that had actual businesses with real customers and positive cash flows.

If 37,000 companies were listed and only 2,300 remain today, where did the other 94% go?

Up to 1,000 of them, or about 3%, were taken over by other local companies. Some of these generated real value for shareholders, for example BHP taking over Western Mining, and the 35 banks that amalgamated into the big four today.

However, the vast majority were mining explorers that were mopped up at very low prices by promoters with high hopes of dressing them up again to take another shot at the next round of gullible ‘investors’. There have been variations on this theme, such as failed miners dressed up as ‘dot-coms’ for the late 1990s ‘dot-com’, then failed ‘dot-coms’ dressed up as miners in the 2003-2007 mining boom, and now failed miners dressed up as ‘fintechs’(e.g. Decimal Software, Bulletproof Group).

There were also around 200 listed companies that were taken over by foreign companies, such as all of the big Aussie brewers, Optus, BRL Hardy, Alinta, DUET, Rinker, and Westfield.

That leaves 33,000 (or so) companies that disappeared.

There were some colossal bankruptcies like Bond, Qintex, HIH, ABC Learning, Babcock & Brown, Allco, MFS, Timbercorp, etc, but most never saw the light of day. They simply ran out of money and de-listed, worthless.

Most of the current listed companies will probably end up worthless

Looking at the still-listed 2,300 ‘survivors’ from the original 37,000 or so (in the right chart above):

- 470 companies (17% of the current list, or just 1.3% of the all companies that have been listed in Australia) are profitable and paying dividends. Although there are 2,300 listed companies in Australia, nearly half of their combined total profits and dividends come from just six companies – the big four banks, BHP and RIO, which are all more than 100 years old.

- 110 companies that are profitable but pay no dividends. Many these probably have at least a decent chance of survival and success.

- 200-or-so listed companies (I am probably being generous here) that make losses and pay no dividends but they might have some realistic prospects for success. Nobody knows which ones they are, but there must be about 100.

That leaves the remaining 65% of currently-listed companies or around 1,500 in the current batch. These are barely solvent and will probably run out of money and suffer the same fate as the 33,000 or so other failures that disappeared worthless.

Why is this important?

It is important in understanding the difference between investing and speculating (gambling).

It is also important for setting expectations about likely risks and returns. When we talk about the ‘All Ordinaries index’ or the ‘the Australian stock market’ generating returns of 10% p.a. for the past 50 years or 100 years, we mean indexes of ‘investment grade’ companies only, which is a fraction of the total number of listed companies.

Even the broadest current index, the ‘All Ordinaries Index’, covers just 490 stocks or 20% of listed companies. Other than the returns from the indexes of the tiny minority of ‘investment grade’ companies, if we were to track down and measure what happened to investors’ money in the other 95%+ of listed companies, it would be a vast sea of red ink, punctuated by the rare huge jackpot for the few lucky winners.

The overwhelming majority of listed companies in any given era are speculative stocks with nothing but hope and hype and almost all will disappear worthless.

I often come across ‘investors’ who point to their portfolios of a dozen or so tiny speculative stocks and say:

“Look, I’ve got a diversified portfolio of lithium mining, wind farms, solar, rare earths, plus some biotechs and this fintech. Even if I don’t hit the jackpot with any of them, I should get decent market returns from them if I hold them long enough!”

In the words of Darryl Kerrigan in the classic Aussie movie, The Castle: “Tell him he’s dreamin’”

We wish them well of course in their quest to hit the jackpot and strike it rich, but that’s gambling, not investing.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.