Global monetary authorities are continuing to engineer a low bond yield environment in an ongoing effort to stave off the onset of economic stagnation. Against this backdrop, interest in infrastructure as an asset class has intensified, offering yields that look appealing to retail investors and liability-driven institutional investors such as defined-benefit pension funds and insurers.

But before simply treating infrastructure as a ‘bond-proxy’, investors need to understand its unique characteristics. Foremost of these is the presence of regulatory risk, which represents arguably the strongest case for treating infrastructure as a separate asset class from broader private equity or ‘real asset’ allocations.

By virtue of their monopolistic positions (underpinned by inelastic demand for essential services and prohibitively high barriers to entry), ‘core’ infrastructure assets such as utilities are typically subject to some form of economic regulation. Not surprisingly, regulatory risk is a key issue. In one survey, it was nominated as the biggest challenge by respondents, outstripping macroeconomic risk, manager selection and other issues.

Complexities of assessing risk

However, assessing and managing regulatory risk can be difficult. For instance, regulatory and political risk are often seen as synonymous. Yet there is an argument that a business directly subject to government decisions should be treated differently to one that has the protection of a separate and independent rule-bound regulator which must balance all stakeholder interests. In the UK, for instance, the water regulator has a statutory responsibility to ensure the financial feasibility of privately owned water companies.

Prima facie, this reduces the likelihood of the regulator imposing an adverse and financially crippling decision. Contrast this with the more heavy-handed fate suffered by the Gassled investors at the hand of the Norwegian government’s oil and energy ministry, and it is easy to see why rule-bound regulators are something of a shield from opportunistic politicians. This distinction has become ever-more crucial in the wake of populist election results such as Brexit and Donald Trump’s US presidential victory.

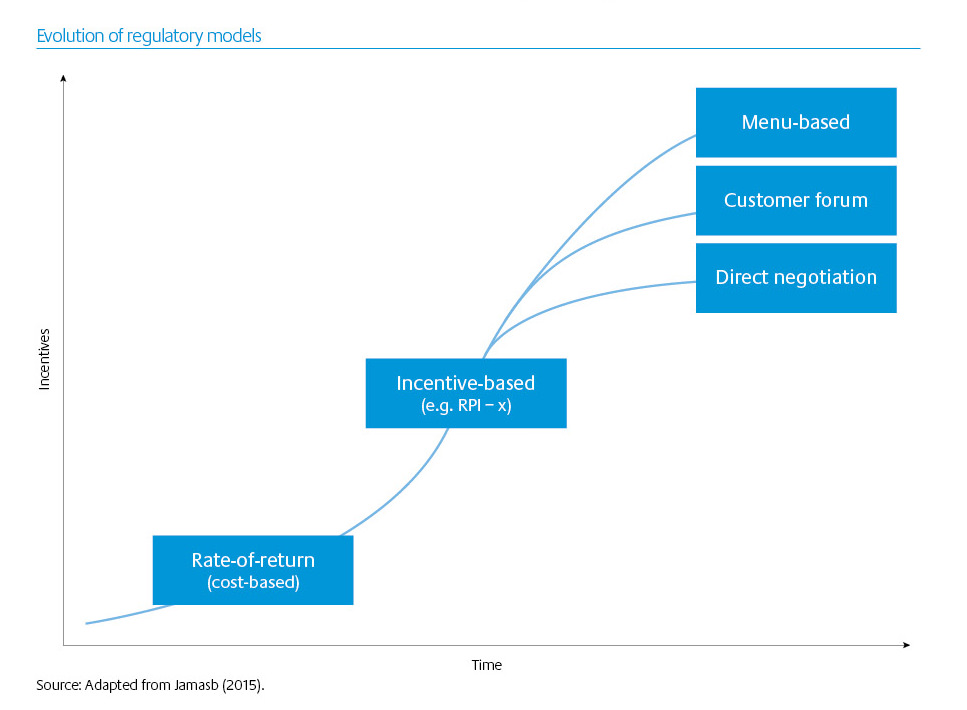

A further layer of complexity stems from the fact that regulation is dynamic, and that regimes can be expected to evolve over time in response to changes in the broader economic, political, and technological environment. Across our portfolio, we have already seen a progression from cost to incentive-based forms of regulation. In some of the more mature jurisdictions we operate in, regulation has evolved further still – with regulators employing a variety of new tools, methods and approaches in response to changing regulatory priorities.

The UK is perhaps the best example of this evolution. Developed in the 1980s in response to the ‘gold-plating’ observed under cost-based regimes in the US and elsewhere, the ‘British model’ of incentive regulation worked very well for two decades (and subsequently was adopted worldwide).

By the late 2000s, however, questions were being raised about the continued efficacy of the incentive scheme. This led to a once-in-a-generation overhaul of regulatory regimes in several UK sectors.

A hallmark of the new systems included smarter mechanisms designed to overcome the classic information asymmetry that exists between a typical regulated utility and the regulator. They also included an emphasis on innovation, ‘capex-lite’ solutions and more direct customer engagement. Regulators worldwide are also seeking to design systems incorporating behavioural economics insights, which have revealed how customer inertia and biases can lead to perverse and costly outcomes.

Investors in Australia are taking note, as it is only a matter of time before some of these features are introduced here. The current political machinations aside, our vast power networks have to contend with the economic reality of high maintenance costs, an increasingly distributed generation landscape and a fit-for-purpose model of regulation.

Changing risk-reward profile of regulated assets

Our view is that these latest innovations in regulatory design will fundamentally change the risk-reward profile of regulated assets. Specifically, they have the potential to increase both outperformance and underperformance. Investors will therefore need to evaluate the ‘alpha’ potential of specific companies rather than seek generic ‘beta’ exposure to a given sector.

Another lesson is that, with so many potential triggers for change, it is dangerous to characterise a historically ‘benign’ regulatory regime as less ‘risky’. Indeed, the opposite could be argued: a regime that has just undergone a step-change can be viewed by investors as ‘de-risked’ for a period of time.

So what are the keys to success in this brave new world of infrastructure regulation? In our view, they include a sufficiently long-term investment horizon, strong shareholder representation and associated control, a proactive approach to stakeholder management and a focus on sustainable, operationally efficient, and customer-driven outcomes.

Ritesh Prasad is a Senior Investment Analyst in the Unlisted Infrastructure team at Colonial First State Global Asset Management. This article provides general information not specific to any investor’s circumstances.