Last week, the US reported annual inflation of 5%, the highest since 2008. Pundits are suggesting investments in anything from commodities to value stocks will protect portfolios from rising inflation. My take is these assets have already run. But the current owners do need someone to sell to, which is why these stories abound. Current inflation is supply-chain based, temporary, and the recent price signals might even create the opposite effect.

Why is today’s inflation different from the 1970s?

The world has changed. The structure of today’s economy is radically different to the 1970s and 1980s.

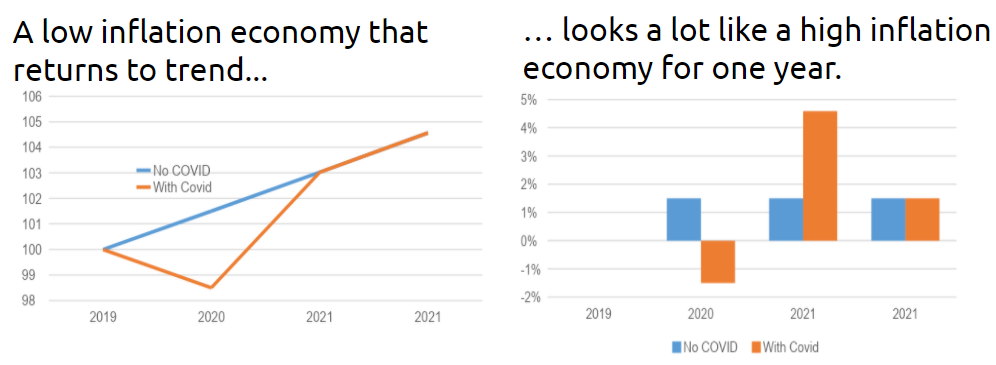

1. Base effects

Most of the inflation is either in the supply chain or comes from starting at a low base, both of which will pass.

Stimulus cheques do create inflation by boosting demand, but a one-period inflation spike does not create ongoing inflation.

2. Economic orthodoxy has been over engineered to prevent inflation

Stagflation was rampant in the 1970s and 1980s. The end came when central banks (led by the US) showed they were prepared to cause recessions to 'anchor' inflation expectations. Just as importantly, new rules were enacted to ensure inflation wouldn’t return:

- Monetary system: Independence from political intervention for central banks, inflation targets, various rules on government money printing.

- Oil prices: The best solution to high commodity prices is high commodity prices. A wave of investment and increased supply meant oil prices stopped rising.

- Deregulation: A range of industries changed from public to private ownership, lowering costs.

The pendulum has swung too far. The steps taken to prevent inflation have entrenched disinflation.

3. Inflation expectations

Low inflation expectations have become entrenched. Employees have stopped demanding continual wage rises. It took 30 years for expectations to fall from 5% to below 2%. A jump to higher inflation expectations is unlikely to be quick.

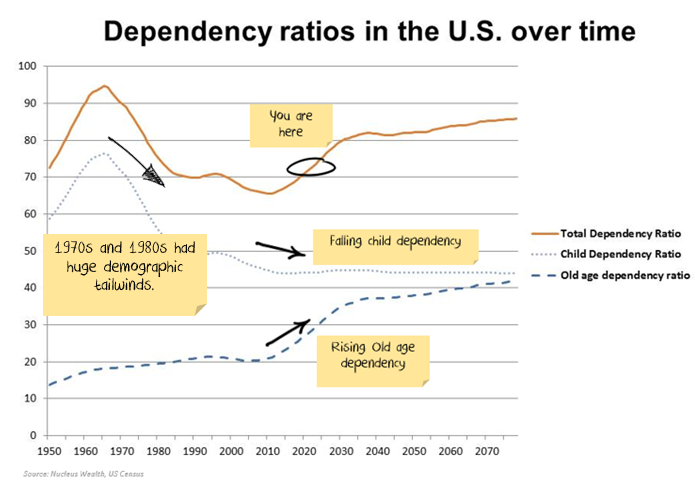

4. Changing economic structures and demographics

In most developed countries, manufacturing has shrunk as a proportion of the economy by a third since the 1980s. Union membership has plummeted. This puts even more focus on wages, as wages are the largest cost for service companies. The 1970s and 1980s saw significant financial reforms which dramatically increased debt levels. While debt is increasing, inflation increases, but high levels of debt are deflationary.

In addition, demographics are no longer delivering an economic tailwind, as shown below in the dependency ratio:

5. Technological innovation

In recent decades, the internet disintermediated entire industries, reducing costs, increasing competition and lowering inflation. Energy and automation will be the drivers for the 2020s.

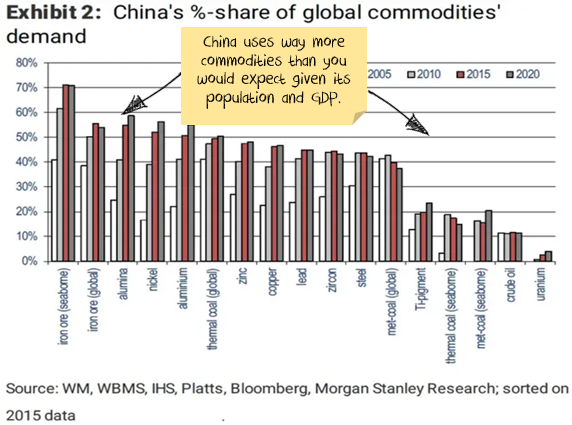

China’s impact on commodity prices

China uses an incredible amount of commodities relative to its size. This is not a long-term phenomenon. It has arisen in the last 20 years:

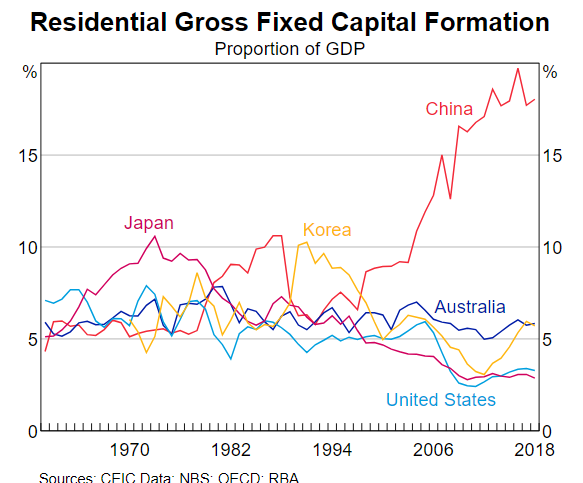

The real culprit is the Chinese construction sector, far more than other infrastructure, and even railways are not as steel-intensive. The big consumer of steel is high-rise buildings.

Residential investment in China, as a proportion of GDP, is double the level of Japan before its housing crash and three times higher than the US before its housing crash.

Over the long term, we expect this to converge to more normal levels, particularly due to demographic headwinds.

What about US infrastructure? Won’t this increase commodity demand? CRU estimates $US1 trillion of US infrastructure will need about 6 million tons of steel and 110 tonnes of copper per year. Both are less than 0.3% of the current world annual supply. The net effect is that commodity inflation is far more leveraged to Chinese stimulus than developed market stimulus.

Again, on its own, this suggests a longer-term downside for commodity demand, but the overspend could last for years. The main reason we are concerned is that Chinese credit growth has come to a halt.

Several investment banks are pitching the story that investors need commodity exposure to protect from rising inflation. A weak Chinese construction market will blow that story out of the water.

There are both long-term and short-term reasons for the construction cycle to be peaking in China. Commodities are standing in the blast zone.

What is an inventory cycle?

The basis of most business cycles has an inventory cycle at the core. The stocking and de-stocking cycles are what typically drive economies both into recession and out of recession.

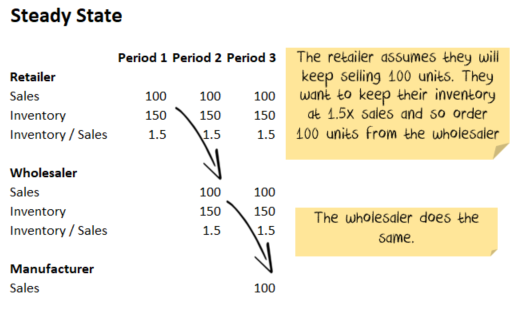

Assume we have:

- A retailer who buys from a wholesaler

- A wholesaler who buys from a manufacturer.

We are looking at the changes from period to period. For some companies, the periods are days. For others, the periods are weeks, months, or quarters. Both the retailer and the wholesaler target 1.5x the current period’s sales as inventory.

It looks like this:

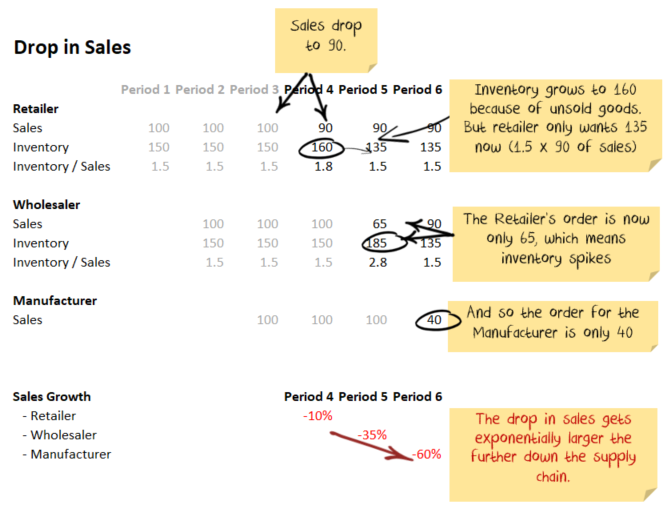

Now let us look at the effect of a drop in demand. Say sales drop 10% for the retailer and then stay at the new level:

As you can see, the effect is more significant further down the supply chain. A 10% fall in sales for the retailer is a 60% fall for the manufacturer. In the initial stages of a recession, this effect worsens the cycle as manufacturers then fire staff and pull back spending. However, it works in the other direction as well. When the cycle turns, the opposite effect kicks in.

An extraordinary convergence = an inventory super cycle

Demand for goods has been temporarily boosted by:

- Lack of other options as services like travel and recreation were shut.

- Government stimulus, both direct and indirect.

- Pent up demand as consumers who built up savings and are now spending.

- A need for greater inventories from businesses to mitigate against future supply shocks.

Meanwhile, supply has been temporarily constrained by:

- Lockdown constraints on workers.

- Changes in demand. For example, more demand for houses, less for apartments. Manufacturers/suppliers need to change processes.

- The Suez Canal blockage.

If we are in a super-cycle where demand increases and then returns to trend, it will be a wild ride for manufacturers. But inventory cycles are short. The price signals of today are building the excess capacity of tomorrow. The signs are good for economic growth but are not indicative of rampant inflation.

How to invest as inflation fears fade

The current rotation into value will not fare well if inflation fades. Indeed, it will be the worst place to invest as equity duration risk disappears for a time. There are three main options as to how the market treats the factor rotation changes:

- Inflation falls back and lifts corporate profits, supporting ongoing high valuations, but 'value' gives way to mid-cycle 'quality'. In this scenario, investors should own longer duration bonds plus quality growth equities.

- Inflation falls, yields collapse and stocks violently rotate back to the 'growth' stock bubble. In this scenario, longer duration bonds rise (yields fall) plus growth equities catch a bid. This is not for the faint of heart. If the non-profitable growth bubble re-inflates, it will be temporary. This scenario is best characterised as a tradeable bear market rally.

- Central banks commit a policy error by following hawkish leads in China, New Zealand and Canada. The Fed tightens directly into the growth and inflation cliff ahead (even discussion of a taper will be enough). This will deliver a growth shock to markets alongside the deflation shock. It will force yields higher briefly before equities tumble. The entire reflation trade could collapse until the Fed reverses course. In this third scenario, a larger allocation of longer-duration bonds is the key. Equity allocations should be cut and repositioned like scenarios one or two.

The three scenarios represent an investment horizon of 12-18 months as the inventory super-cycle and commodities bubble deflate owing to a combined Chinese and US growth air pocket that ends the great stimulus and global reopening boom.

From there, we will still have low unemployment in the US with a large Biden stimulus lifting US growth towards 3% per annum for years. This holds out the real prospect for better wage gains and a grind higher for inflation through the cycle.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.