Nothing scares investors more than talk of a recession. However, history shows that economic contractions have been mostly good for share prices and the Australian share market has actually increased during the majority of economic recessions in Australia. The same is true for the US share market during US recessions.

Timing is key

How is this possible? The key is timing. What causes share prices to fall is the fear of impending recession, not the recession itself if, or when it finally arrives. Share markets have almost always rebounded out of the middle of recessions, while the economy is still contracting, while profits and dividends are still being cut, and while news headlines are full of gloom and doom, rising unemployment, corporate layoffs and bankruptcies.

Recessions and depressions

First, some definitions. An economic ‘recession’ is generally, but not always, defined as two or more consecutive quarters of negative economic growth. The most recent exception to this definition was the 2020 Covid lockdown recession, when the US National Bureau of Economic Research (the body that calls US recessions) declared a ‘recession’ in the US lasting just two months (February-March 2020).

Before the 1940s, every economic slowdown was called a ‘depression’, but now the term is reserved for much deeper and longer economic contractions than mere recessions, accompanied by very high unemployment (say 20% or more), significant and sustained declines in aggregate incomes, commodities prices, trade and credit. In Australia, the main economic depressions were in 1930s, 1890s and 1840s, which were all global crises.

Timing between the start and the rebound

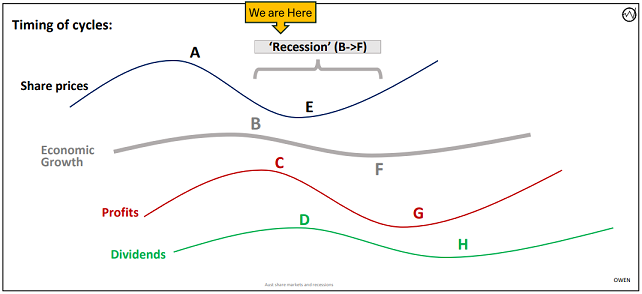

Share prices generally fall before economic contractions start and then start rebounding while economies are still contracting. This chart illustrates how the cycles work:

The timing of each part of the cycle almost always follows the following order:

A. Share prices start falling in anticipation of profits falling in an upcoming economic slowdown but while aggregate company profits and dividends are still rising.

B. Economic activity starts contracting (such as negative growth in real GDP). Because of delays in reporting national economic numbers, by the time negative growth is reported, the share market has already been falling for several months in most cases. Even the short, sharp 2020 Covid recession, when the March quarter economic contraction in Australia was announced in May, the share market had already started to rebound strongly from late March.

C. Aggregate company profits start falling due to slower revenues and often rising interest rates, usually well after share prices have started falling (A), and also usually after economic activity starts contracting (B). Often, some company profits are still surging well into economic contraction. Aggregate company profits fall by much more than the reduction in economic output because companies have operational and financial leverage, and narrow profit margins. For example, in a serious recession, GDP might fall by say 3%, but aggregate profits and share prices might fall by 30-40% or more.

D. Dividends start falling, but cutting dividends is usually the last resort of company boards in a crisis. Generally, companies try to maintain dividends in order to retain investor confidence and support the share price, even though profits have fallen. The fall in aggregate dividends is always less than the fall in aggregate profits.

E. Then share prices start rebounding, usually while economic activity is still contracting in the middle of a recession, while profits and dividends are being cut.

F. The economy starts growing again but well after the start of the rebound in share prices. In most cases, by the time the economy starts growing again, share prices have more than recovered their falls during the recession itself. As a result, the actual periods of recessions (when economic growth is contracting, from points B to F), share prices actually rose in the vast majority of cycles.

G. Aggregate company profits rebound, well after start of rebounds in share prices (E) and economic growth (F).

H. Dividends are finally raised, as balance sheets and profitability are restored – well after the start of the rebounds in share prices (E), economic growth (F), and profits (G).

The net result of this consistent pattern is that the share market has risen during the vast majority of economic recessions (point B to point F on the chart).

Where are we now on the chart?

The US (which drives all global markets) and Australian stockmarkets are probably around point B on the chart. Share prices have already fallen in anticipation of rate hikes cutting into consumer spending, leading to lower corporate profits and dividends, job losses and economic contractions. Whether or not there is a recession is not as important as the fear of significantly lower profits and dividends.

Although the US economy actually contracted in the first two quarters of 2022, the National Bureau of Economic Research is not yet calling it a recession as household spending and jobs remain strong. Also, corporate profits and dividends are still rising, albeit at slower rates than in 2021. Australia also has strong jobs, spending, profits and dividends. Even in Europe and the UK, economies are probably already contracting, but jobs, spending, profits and dividends remain strong, although China is contracting.

Large sections of the US share market in particular are still over-priced, although the Australian market is probably now around ‘fair value’. When economic recessions do arrive, they will be marked by mass job losses and bankruptcies, as in numerous previous cycles. When sharemarkets rebound, it will be when doom and gloom is greatest, unemployment and corporate failures are rising, and companies are posting big cuts to profits and dividends. Rebounds have always been faster and stronger than investors expect, and they start when fear and uncertainty are greatest (when there is ‘blood in the streets’, says Warren Buffett).

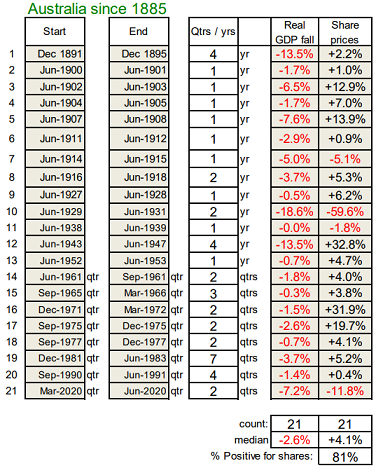

21 recessions in 150 years

Australia has had 21 recessions since the 1880s, based on the conventional definition of at least two consecutive quarters of negative growth in real GDP.

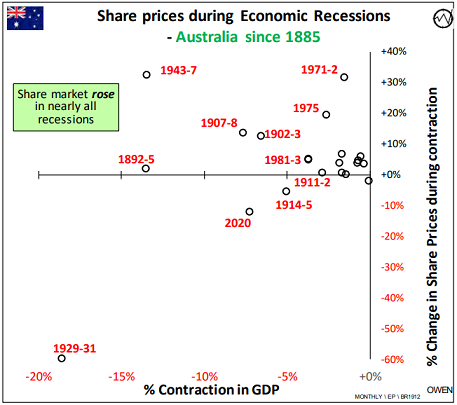

The next chart shows changes in the share price index during each of the recessions since the 1880s in Australia. Almost all are in the upper sector of the chart – the broad sharemarket rose during the recessions.

In summary:

- The broad sharemarket index rose during 17 (81%) of the 21 recessions in Australia since the 1880s.

- Aside from the very short, sharp 2020 Covid sell-off, share prices rose during each of Australia's previous nine recessions, since the 1938-39 recession, when share prices fell by just 1.8%.

- In the recent well-known recessions, sharemarkets rose during each of them. These included: Keating’s 1990-91 ‘recession we had to have’, the long 1981-83 recession, the 1975 Whitlam inflation recession, and the 1971-72 mining collapse recession.

Recessions (contractions 2q or longer)

Aside from a couple of minor share price falls during the 1938-39 recession and the 1914-15 WWI recession, the only recession or depression in Australia that was accompanied by big share price falls during the period of the economic contraction was the 1929-31 depression when shares fell by 60% during the period of contraction.

In fact, some of the best years for shares are when the economy was contracting or still weak, including 1983, the best ever calendar year for Australian shares (up 60%), during the 1981-83 recession.

This is a reminder to ignore media scare mongering. In particular, by the time the recession hits, most of the share market fall is probably already in the past. The great share market surges start when the media headlines are full of doom and gloom, rising jobless rates, corporate bankruptcies, losses, and dividend cuts.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.