Following the global financial crisis, many investors came to expect a new normal of slow economic growth, negligible inflation and sustained low interest rates. Cyclical swings in the economy, inflation, and bond yields largely disappeared from investment discussions.

Since the second half of 2017, this new orthodoxy has been challenged by quickening growth in the global economy and by inflation reappearing in the US, causing bond yields to quickly move higher. Share markets turned choppy and, for a while, extremely gloomy.

This isn’t the first time widespread predictions of the taming of the cycle in the economy and investment markets had taken hold – and proven to be wrong.

Why do economies and investment markets have cycles?

Cycles occur because we are affected by the optimism or pessimism of others, because governments and central banks often change their policy settings ‘too much’ and ‘too late’, and because of the big swings in credit.

No two cycles are ever the same. Cycles aren’t rhythmic. Previous cycles have been affected by globalisation, the IT revolution, China’s modernisation and the float of the Australian dollar, but less than is generally realised at the time.

Let’s look back on two earlier episodes from the last 70 years when many investors believed the cycle was tamed permanently. In my view, we’re at another point in time when cycles will reassert themselves.

Example 1: The 1950s and 1960s were the heydays of the so-called ‘Keynesian revolution’. Confidence abounded that the business cycle could, and would, be contained by economic management. Governments would ease their budget settings when economic activity was slack and tighten when economic activity was buoyant.

For a while, it seemed to work well. Unfortunately, governments were too keen to use stimulative policies and too reluctant to introduce policies of restraint. Public debt grew to be uncomfortably high and expectations formed that governments would set their economic policies to maintain full employment even as rates of increase in wages and prices moved significantly higher. An inflationary psychology built up and morphed into stagflation. By the 1970s, cycles in the economy and investment markets became very wide.

Example 2: As a result, the ‘fine tuning’ of economies was downgraded and increased emphasis was put on ‘policy rules’, such as allowing central banks greater independence to pursue low inflation. For a while, these changes, too, seemed to work well. From the early 1980s to the early years of this century, the economic cycle in the US and many other countries was mild.

A report from the US central bank records this episode:

“Reducing inflation and establishing basic price stability laid the foundation for the great moderation. But in looking for deeper reasons, economists have generally proposed three reasons: changes in the structure of the economy, good luck, and good policy.”

Alas, these good times came to generate excessive optimism – and borrowing – and brought on the sub-prime debt crisis and the GFC. Within six years, the new moderation was replaced in North America and Europe by the ‘great recession’; the cycle was back.

The last decade

Following the GFC, many investors and strategists believed governments and central banks could no longer raise rates of economic growth above stalling speed. Low inflation and low interest rates were here to stay and the business cycle was dead again.

A minority view, perhaps strongly influenced by the writings of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff on eight centuries of financial folly, was that severe financial crises were always followed by a lengthy slump in confidence, low growth, and little inflation, but these periods are a drawn-out phase within the economic cycle, not a permanent structural change.

Inflation is the dominant influence on interest rates. The massive decline in bond yields over the past 40 years took place in three phases, each of them following a decline in inflation.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, most countries had experienced very high inflation. In response, central banks lifted cash rates to record levels (20% in the US and 17.5% in Australia). Inflation was brought to heel, though at the cost of deep recessions and big cyclical increases in unemployment. Inflation was further restrained in the 1990s by globalisation (including the availability of competitively-priced manufacturers from China) and by the IT revolution (which gave consumers an unprecedented ability to shop around).

Has inflation died, or just been in hibernation?

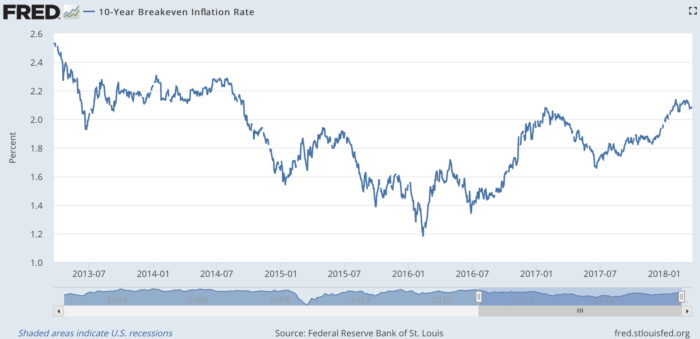

The GFC fuelled fears of world-wide depression and deflation. As things turned out, there wasn’t a depression, but inflation just about disappeared (to be replaced by fears of deflation). Since the second half of 2016, some influences – including intense competition from Chinese manufacturers – that had caused rock-bottom inflation around the world started to loosen their grip.

Recently, however, a significant number of investors have become concerned inflation is on the way back, initially in the US and later in other countries. They focus on: the narrowing in output gaps in most economies; the spurt (and synchronisation) in world growth since late 2016; the substantial easing legislated for US fiscal policy; the rebound in energy prices; the quickening in wage increases in the US and views that wages have troughed in other countries; and political populism including the unfortunate move by the US to impose tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium.

Implications for investors

It’s a good time to be focusing on the return of the cycle in inflation and bond yields. For a year or so, the impact could well be reasonably mild, but later may be disruptive. The implications are:

- Investors need to allow for heightened volatility as markets adjust (and at times over-adjust) to the return of inflation.

- Bond investors might favour variable-rate securities, short-dated bonds, positive return bond funds and inflation-linked bonds.

- Traditionally, average returns from shares are boosted when inflation lifts from negligible to mild rates but should inflation quicken from moderate to high rates, it’s generally bad news for share markets.

- Real bond yields, not nominal yields, matter for share market valuations. Were bond yields to rise to, say, 4%, the negative impact on shares would likely be more marked if inflation was 1% than if inflation was running at 3%.

- Share investors also need to consider the cause of the spike in bond yields: Is it stronger economic growth, or are central banks moving too quickly to tighten their monetary settings?

- As interest rates rise, shares seen as ‘bond proxies’ will likely underperform, particularly shares in capital intensive businesses with heavy debts, that’s because their costs increase when assets are replaced.

- Higher interest rates also tend to dampen or weaken the property market and make property more uneven and selective.

Don Stammer has been involved with investments since the early 1960s. Now semi-retired, he is an adviser to Altius Asset Management and Stanford Brown Financial Advisers. The views expressed in this article are his alone.