Adam Smith is probably turning in his grave at the moment as the invisible hand of the price mechanism he described in The Wealth of Nations is fettered by central bank money printing. The main tenet of the modern capitalist economy is that price is used to clear supply and demand and efficiently ration scarce capital. Capital markets sit at the centre of such an economic system, pricing risk and allocating capital.

When central banks fix the price of money near zero by making its supply almost limitless, what sort of economic outcomes should we expect? Have central bankers discovered the magic bullet for all our previous economic woes?

The answer to recessions is now clear - print money!

The famous value investor Benjamin Graham described the market as a voting machine, tallying the views of a myriad of investors to drive a price for the value of companies. In normal times the wisdom of crowds suggests that this view is often the most accurate prediction of the future.

In reality, the market is an extremely sensitive barometer of liquidity. The modern economy is circular with banking and capital markets sitting in the centre. Money is either created or destroyed by the rate at which it circulates around the economy. When economic activity slows then credit creation wanes and liquidity comes under pressure. This is often visible in declining stock prices as a real time measure of economic activity.

Therefore, the market isn’t so much a great predictor of the economy, rather it is highly sensitive to its operation. It’s no wonder that central bankers pay a lot of attention to it and react strongly to falls.

How effective are zero interest rate policies and QE?

Injecting liquidity into a seizing banking system is certainly a good short-term policy response and has proven effective in limiting the downside from the GFC and containing financial system stress in the current recession. However, did keeping policy rates below inflation in the developed world for the decade after the GFC produce a superior outcome?

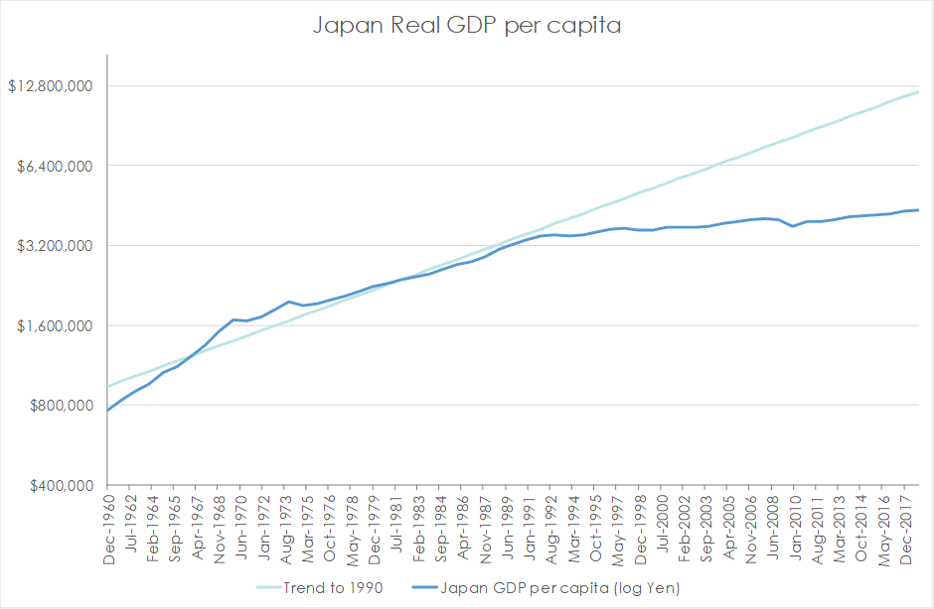

As the economy which employed zero rates for the longest time, Japan offers an interesting test case. The following chart shows that after the bursting of their very leveraged housing bubble and a subsequent banking crisis, the Japanese economy has grown at a significantly slower rate.

Growth in real GDP per capita, a measure of the contribution of productivity to economic growth, rather than that from population growth or inflation, has been lacklustre.

There are many reasons for Japan’s economic performance, but the slow deleveraging of its housing bubble, exacerbated by an ageing and shrinking population, is key. For many years this asset deflation created a banking system that was technically insolvent and unprepared to take risk and lend. It also impacted confidence and spending patterns that saw the household sector spend the next 25 years deleveraging. Looking at this experience, it’s no wonder that central bankers today are prepared to do whatever it takes to prevent an asset price deflation cycle.

Such a slow recovery makes you question whether zero interest rate policies and QE are effective or whether Japan was a unique case. The argument for low interest rates is that it encourages businesses to borrow to invest and create jobs. However, there have also been many criticisms, including that it encourages zombie companies to persist, destroys income for many and creates a moral hazard around leverage and risk taking.

From our perspective, one of the key negatives is that encouraging growth through increased leverage makes the economy vulnerable to further shocks. Even lower rates will then be needed to cushion the shock and create more leverage for growth. Part of Japan’s problem was an unwillingness to take short-term pain and instead to socialise the costs of the financial collapse. They accepted lower growth in the long run for higher employment in the short run.

When dealing with economics, there are often a lot of circularities and feedback. It can be difficult to distinguish between causation and correlation. Are low rates caused by weak growth or does weak growth cause low rates? It’s possibly both with two-way feedback. Zero rate policies don’t appear to be an effective means of driving long term productivity growth. The US certainly performed better than Japan following its financial crisis.

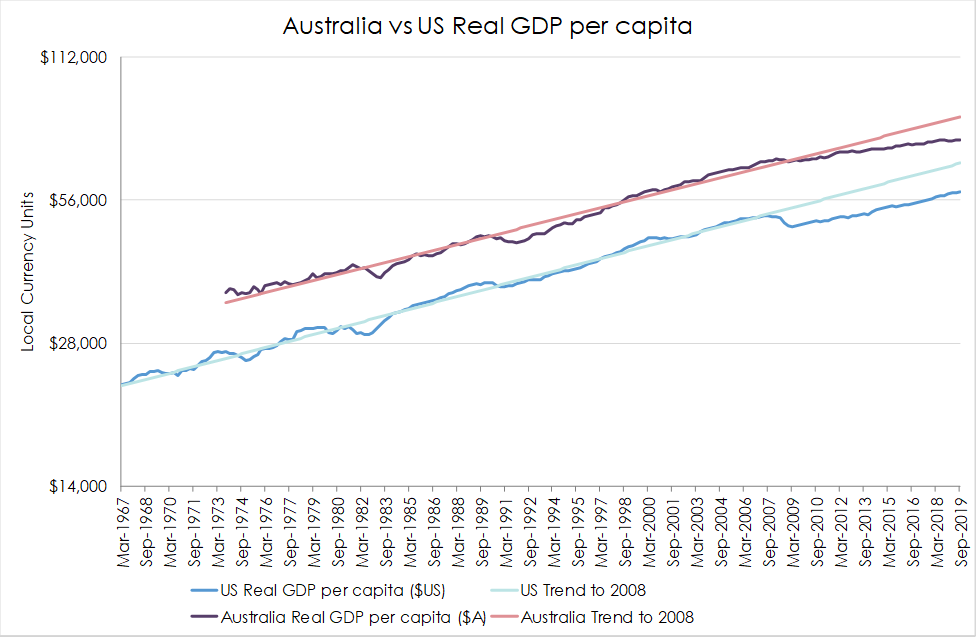

The following chart highlights that while the US didn’t recoup the losses to return to trend like it did in previous recessions, it did at least return to a similar trend growth level.

The US had a faster short-term adjustment than Japan through bankruptcies, unemployment and a more rapid deleveraging of the household sector. Through this period the US also experienced a massive positive economic shock from the shale oil boom. It has now eclipsed Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s largest oil producer and a net energy exporter. The return on capital from much of the shale oil investment is highly questionable, but it has driven economic activity and employment.

The fact that the US didn’t perform better post the GFC despite this boost to activity raises questions around the benefits of the zero rate policies and successive rounds of QE. They were certainly necessary initially to fix a broken system, but while the US has recovered towards the previous trend in productivity, it has failed to recoup the losses of the GFC.

Australia’s economic performance, in a productivity sense, has been worse than in the US. This anaemic growth has been obscured by high levels of migration which have boosted total GDP. The economic performance of the last decade has significantly trailed the recoveries from the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s. This raises the further question of whether avoiding a recession at any cost is worth it in the long run?

Why has Australia’s performance been so poor?

One reason may be where our investment boom has taken place. Holding real rates below zero might not be great for capital allocation, as Australia has continued to invest heavily in housing: a little bit in the construction of new houses but a lot in the value of land. Increasing the value of land does nothing for the productive potential of the economy.

Rising house prices stimulate development activity in the short term and through wealth effects drives demand for second homes and holiday houses. According to the latest census there were 8.3 million households and 9.3 million private dwellings, so, it would appear, a lot of holiday homes. Stimulating house prices through low rates helps drive activity in the short term and preventing household deleveraging has limited downside recession risk. The cost though is one of the highest levels of household debt in the world.

The high level of gearing also makes households more financially fragile so that any economic hit risks a deleveraging cycle. The medium-term impacts of a huge allocation of investment to a non-productive area and the increasingly fragile confidence have created a poor economic outcome for Australia over the last decade. It’s not clear how doubling down on these distortive policies will produce a better result over the next decade.

What you can be sure of is that there isn’t going to be a long queue of central bankers looking to normalise these policies. The tough global recession will leave high levels of unemployment, underutilisation of capacity and likely deflationary pressures. We’ve probably got at least another decade of distortive policies keeping interest rates anchored around zero.

What is market pricing currently implying about the outlook?

Risk assets have rallied strongly across the board, starting with bonds and flowing through to credit and equities. Prima facie it looks like everything is good, we have had a brief exogenous shock, but it will largely roll through and things will get back to normal. That message seems at odds with a lot of the economic data and the fact that the coronavirus is still spreading around the world at an increasing rate, particularly in emerging markets. Central bank liquidity is swamping economic effects, so that market pricing has disconnected from economic fundamentals. The impact of this liquidity support is best highlighted by the collapse in US high yield credit spreads as seen in the following chart.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

What are the risks around this dynamic in the short term?

A mea culpa from central banks is highly unlikely, but an attempt to normalise rates and liquidity as policy makers take comfort from stronger markets is possible. Another risk is that the economic dislocation drives solvency issues across the global economy, followed by a deleveraging cycle and a credit crunch that overwhelms efforts to inject liquidity. While this may eventually lead to a more robust recovery the near-term impacts would be devastating for markets.

The only appropriate investment strategy while market pricing signals are heavily distorted by liquidity is one that is neutral to the inconsistencies building between prices and earnings across the market.

In this environment it is dangerous to take comfort from rallying markets and cyclicals starting to outperform. It is also fruitless to fight against it. Markets are largely being driven by government policy and sentiment can shift rapidly, leaving investors stranded when pursuing a style tilt. The current rally in value stocks is sustainable for a time as liquidity drives markets higher and optimism and risk appetite are buoyed. However, in the medium term we expect growth and inflation to remain anaemic as distortive policies and excessive leverage weigh in. With markets increasingly distorted and disconnected from fundamentals, style neutrality takes on even greater importance in an investment process.

Sean Fenton is Chief Investment Officer at Sage Capital. This article contains general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Sage Capital is an investment manager partner of Channel Capital, a sponsor of Firstlinks. For more articles and papers from Channel Capital and partners, click here.