Tony Togher is Head of Short-Term Investments & Global Credit at First Sentier Investors, which is responsible for about $60 billion of client investments. He started his career in 1983 in the Commonwealth Bank’s Global Treasury Division and moved to Commonwealth Investment Management in 1988, which was part of the merger with Colonial First State in 2002. In 2012, Tony was appointed to the Market Governance Committee of the Australian Financial Markets Association (AFMA).

GH: What has been the biggest change in cash and liquidity management since the GFC?

TT: The trade-off between liquidity and returns has become a major part of decision-making. Before 2008, little, if any, margin was attributable to illiquidity. Investments like RMBS (Residential Mortgage Backed Securities) were paying single-digit margins above swap in mid-2007, as were long-term floating rate notes issued by banks. But they offered poor liquidity making them a buy and hold. Diversification was an important part of portfolio management but liquidity was often ignored.

We learned in 2008 that the requirement for liquidity should never be underestimated, especially its unavailability in times of severe stress.

GH: When the market for many securities simply closes.

TT: Yes. So now we have more decisions to make. For liquidity-style portfolios, exposures must be to securities which always have the best liquidity (we call it ‘omnipresent’). Or, we can determine that a proportion of a cash portfolio can accept less liquidity, but we want to be paid for that.

GH: You need to be rewarded for less liquidity with better margins.

TT: I say to clients that we have a ‘liquidity component’ versus an ‘income component’ of a cash book. Some of the income securities do not have the same level of liquidity, and we benefit from our experience with the counterparties for various securities.

GH: Do all banks buy back their own securities to give investors liquidity?

TT: Usually, but it’s best endeavours, they don’t need to buy, but they want to honour the liquidity ‘contract’ and maintain a market in their own paper.

There is also now a clear distinction between a bank term deposit and a bank NCD (Negotiable Certificate of Deposit). It’s exactly the same credit and exactly the same term, it’s exactly the same issuer under the Banking Act, but one has liquidity and the other doesn’t. What price for that liquidity?

GH: And bank issuers are willing to pay more on TDs than NCDs?

TT: Yes, because bank liquidity regulations give the TD a benefit to the issuing bank. But for us as an investor, a TD is not ‘repo-eligible’, so we cannot sell to as a repo (Editor Note, a sale and repurchase agreement generates liquidity for an agreed term). And a second-tier bank outside the four majors will pay extra on a TD, tens of basis points depending on the institution, their credit rating and the tenor.

GH: The four majors all trade at the same rate?

TT: Yes, although we all know that of the $120 billion or so of NCDs on issue by the four majors, none of them could buy back all their paper tomorrow, but their NCDs are the undoubted liquidity in the market.

There are rarely questions about credit limits for the four major banks (and Treasury Notes if available) and everything else trades at a margin. This was one reason why the Council of Regulators reshaped the BBSW pricing metric to derive from transaction activity as opposed to simply posting bid/offer spreads where 10 or 12 providers were involved. We no longer have dealers simply transacting at BBSW, and all transactions are now negotiated with reporting obligations. So the transactions undertaken form the BBSW price.

GH: What other scope is there for extra investment returns?

TT: Well, an innovation we helped to develop resulted from the introduction of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio in 2012 and into 2014. New rules were imposed relating to the liquidity capital requirements banks must adhere to for all assets maturing in 30 days or less, so the non-call deposit developed, moving the maturity outside that window. Then these products moved from 31 to 35 days as banks worried about the one day ‘cliff risk’. Then came the Net Stable Funding Ratio rules in 2018, where structures allowed a conversion into a longer-dated security after a call. This instrument gives liquidity through the converted security (normally NCDs).

GH: Do investors think about cash differently in the last dozen years?

TT: From a funds management perspective, the notion that cash is a temporary place while looking for a better opportunity has changed. For example, in 2007, many investment funds had a cash allocation of zero because they wanted to fully allocate into higher-returning asset classes. But post 2008 they realised they needed cash because there are a wide range of circumstances where cash is required to facilitate a transaction.

For example, on cash-collateralised derivatives, where counterparties must put up cash due to the change in the profile of a currency hedge. Every insto now monitors credit risk exposure on derivatives and may require a cash top-up based on the mark-to-market. There’s much more focus now on reducing the credit risk inherent in any transaction.

GH: In the $60 billion or so of securities you hold, how do you assign between the income and liquidity portions you talked about?

TT: The trade-off is usually specified by the client. A client with good insights into their cash flow forecasting may allocate more to the income space. We also run pool products where we make an assumption on what is appropriate for most investors.

GH: Can we turn to the funds you have available to retail investors including SMSFs. What's in your Wholesale Strategic Cash Fund, available on many retail platforms.

TT: The dominant securities are NCDs of major banks. There is also an allocation to term deposits and convertible deposits (which convert to an NCD upon call) and Treasury Notes. There are floating rate notes, largely issued by banks but some corporate securities, and an allocation to triple-A mortgage-backed securities.

GH: And what return does an investor earn at the moment?

TT: It’s about 0.5% above the cash rate on a gross basis, then depends what fees the platform takes. The gross running yield today is about 1.25%.

GH: You’re also responsible for global credit, so same question, what returns does an investor achieve on the Wholesale Global Credit Income Fund at the moment?

TT: It holds about 440 global securities and the goal is to swap back all returns to Aussie dollars and floating rate (Editor note, short duration risk, not long term). It’s a widely-diversified allocation to global credit, given credit in Australia is highly concentrated in the financial sector. Our goal over time is to achieve a gross return of 90-day BBSW plus 150 basis points (1.5%), and we’ve achieved 157 basis points (1.57%) annualised over 20 years through the cycles. It has an allocation to both investment grade and high yield.

GH: How do you decide the high yield allocation?

TT: It is dynamic. It can be up to 25% of the fund or as low as zero. I believe we have better insights and the ability to provide value in that sector than most of our clients. Simply put, as yields compress we tend to become far more selective, and as yields expand, we allocate more. It's not a trading mentality, it’s more a ‘value-for-risk’ allocation. The gross running yield is about 2.20% at the moment.

GH: Do you see much ‘reaching for yield’ in your space, the quest for yield at the expense of quality?

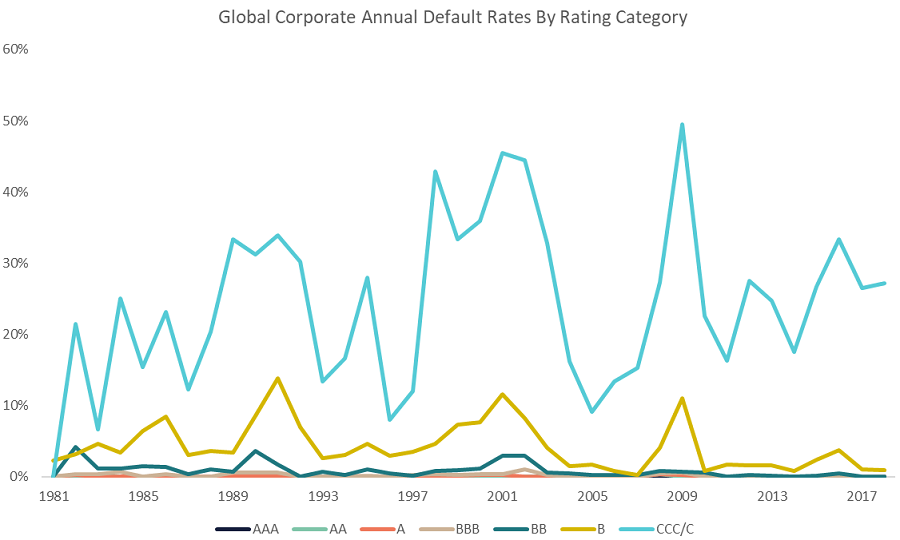

TT: Yes, some people have been more willing to take on credit or illiquidity risk to achieve a higher return, but credit margins are not at historical lows. They were lower prior to 2007. Indeed, high yield is not as tight as it was in December 2018, since then it has moved out from about 300 to 380 over swap. In fact, during the Fed tightening phase in 2018, it blew out to over 500. It’s also moved out in recent days due to the coronavirus implying a higher likelihood of default. It’s a volatile spread and a manager must be very diligent in allocating capital to the sector. As a chart on default rates shows, investors should recognise that lower-rated issuers will have more defaults over time.

Sources: S&P Global Fixed Income Research and S&P Global Market Intelligence's CreditPro®.

It’s also important to focus on ‘loss-given-default’, that is, how much of your money you get back after default. There might be a default, but you get back 50% of your money.

GH: How long will cash rates remain below 1%? Is it five or 10 years?

TT: I don't think it will be a short period of time. The central bank accommodation is designed to re-inflate the economy, and the first sign of that happening will be wage inflation. Globally, I don't think having spent a decade trying to generate activity that central banks will rush to the table to stymie inflation. Anyone waiting for adjustments in rates upwards will need to be very patient.

GH: I have known you for over 30 years. One of the things that you say is that in this business, there are no degrees of honesty. What does that mean to you?

TT: That was a quote I heard when I joined the Commonwealth Bank as a fresh-faced new employee in March 1983. It always stuck with me as a truism. I’ve used it as a guide to what I am doing. Are we being open and honest? Would we be happy for this to be public knowledge? We are fiduciaries of client money.

GH: Final question, after nearly 40 years in a similar role with one company, what motivates you to continue?

TT: I guess the role is never similar, it evolves as dynamic markets change. I’ve worked with interest rates in the high teens and now sub 1%. This market is never boring, and the requirements of clients and investors are always changing. It’s a constantly-evolving process.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. He worked with Tony Togher in various roles including at Colonial First State before the platform and investment functions were separated. The funds management business became Colonial First State Global Asset Management, and following the sale by Commonwealth Bank to Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation, it changed its name to First Sentier Investors, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more articles and papers from First Sentier Investors, please click here.