Even before COVID-19, there were few topics as polarising in politics and economics as the size and rectitude of government debt levels around the world. Fighting to avert economic depression and keep the financial system operating in the face of a ‘once in a lifetime’ global financial crisis (GFC), governments ran up towering fiscal deficits that, in most cases, are still with us today. Now, little more than a decade on, instead of being the once-in-a-lifetime event it was touted as, the GFC is looking like a mere entrée to the main Covid-19 borrowing event.

Cheque, please?

According to the IMF, gross government debt will rise by a staggering US$6 trillion in 2020, a greater increase than was seen in any of the years of the GFC. Moreover, it is a rare optimist that thinks 2020 will see the end of this pandemic, or its economic damage.

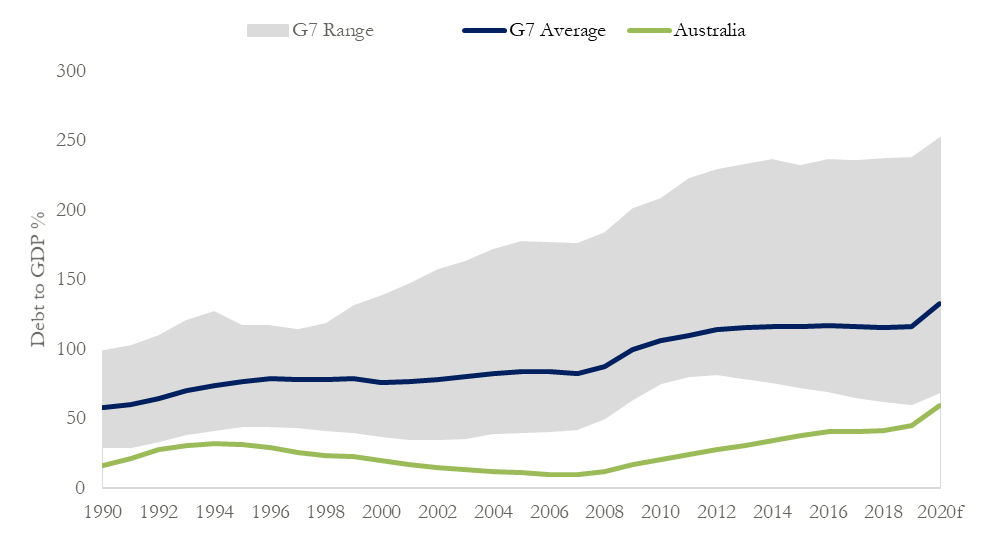

Figure 1: General gross government debt to GDP – G7 countries and Australia

Source: IMF, Fiscal Monitor – April 2020

The post-GFC debt burdens were highly divisive. In academia, a significant split emerged: Are higher levels of national debt dangerous, or do they represent prudent policy at a time of low interest rates? In 2010, two Harvard economists, Carmen Reinhard and Kenneth Rogoff, published a paper which argued that increased levels of government debt lowered a country’s rate of economic growth. Importantly, their work identified a number of key tipping points, the most alarming being when a country’s public debt to GDP ratio exceeded 90%, its economic growth should be expected to halve. With many countries’ debt levels then precariously close to this level, their analysis became a rallying cry for those that believed in fiscal prudence and austerity.

Embarrassingly, critics later uncovered a series of errors within Reinhard and Rogoff’s analysis. And while subsequent papers by the authors, and independent work by the IMF, also found that rising levels of debt do reduce economic growth rates, the relationship was weaker than previously thought, and there was little evidence to support the 90% debt-to-GDP tipping point. However, by then, the schism within the field of economics was already entrenched.

The most favoured and least painful solution to all debt problems is to grow your way out of them. When viewed in this way, increasing levels of government debt can be thought of like a factory that takes out a loan to expand. So long as the investment increases earnings by more than the interest on the loan, over time, the higher earnings pay back the debt.

What matters less than the size of debt, then, is its cost and whether it will be put to productive use. Across the rich world, government borrowing costs have fallen to almost zero, in some countries they are even negative. Faced with the prospect of ‘free’ money, who wouldn’t want to invest to expand the factory? When considering genuine long-term investment into an economy’s future capacity, this logic is hard to fault. When the Australian government can lock in ten-year debt today at less than 1% per annum, how could there not be a better time to be building the hospitals, airports and roads of the future.

Have cheque book, will spend

Taken to its furthest, the debt is ‘costless’ argument forms the foundation of some of the more extreme economic ideas that have arisen since the GFC, such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). In essence, the key insight of MMT is that government borrowing is manifestly different from the borrowings of households or businesses. Why? Because if governments can issue their own money, their supply of currency is endless.

If you need to stimulate the economy, or want to embark on some Gosplan-like spending initiative (in the US, some proponents of MMT see it as a way to pay for things like a ‘Green New Deal’), all you need to do is increase the deficit. If interest rates go up in the future, and debt is no longer so cheap, you just borrow to meet those costs too.

In their defence, the more reasoned MMT campaigners do not claim that large government deficits have no consequences at all. Rather, they claim there is significantly more capacity to use government debt than we have historically believed. Japan is typically held up as an example, having successfully managed debt to GDP ratios of >200% for many years. Perhaps undermining this, however, Japanese growth rates have collapsed in tandem with the country’s ever-increasing debt load.

Ideology is like your breath: you never smell your own

The truth is, we still have an incomplete understanding of the long-term consequences of large national debts, and there exists enough intellectual cover for those on both the left and the right to advocate their existing ideological positions. In politics, the media and around the dinner-party table, most people’s views on the virtues of government debt were firmly established before the pandemic struck. What is unfortunate about this is that it is going to make a reasoned debate about the challenges to come almost impossible.

Given all of this, perhaps it is best to acknowledge that, regardless of its impact on growth, increasing levels of debt indisputably escalate overall risk, and tie our hands in the future.

Today, countries that have treated national indebtedness as a scarce resource outside of times of crisis are the ones that find themselves with the greatest capacity to protect their economies. For years, Germany was criticised for pursuing its schwarze Null (black zero) policy—a commitment to run government surpluses. Vindicated today, and uniquely in Europe, Germany has had the ammunition to launch a substantial stimulus plan. Luckily, Australia also finds itself in this camp and has launched the second largest economic stimulus package in the world. Like Germany, it retains plenty of scope to add to this if needed.

We all hope that the ‘second wave’ proves to be manageable and that ultimately a COVID-19 vaccine is found. Hope, however, won’t keep the lights on if this doesn’t prove to be the case.

Miles Staude of Staude Capital Limited in London is the Portfolio Manager at the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.