Uber - $US50 billion + (and rising quickly)

Snapchat - $US15 billion

Airbnb - $US20 billion

Realestate.com.au - $A6.5 billion

Freelancer - $A500 million

For anyone familiar with valuing assets in any sector other than early stage technology, there is an understandable confusion and mistrust about the numbers listed above. The golden rule of valuations is ‘what someone else is prepared to pay for it’ and regardless of what analysts in other sectors believe, investments are being made at these valuations, right now.

Have these investors taken leave of their senses, or is there something else going on?

A parallel can be drawn to the residential property market, where houses sold a year ago are back on the market at significantly higher levels. With property, there are both external and internal factors at play. We understand these and we can explain them, even if we shake our heads at the extent of the changes.

Technology valuations are also driven by both external and internal factors, which are less understood. Why? Residential property has been around for a long time, tech has not. It takes time and a lot of transactions for the valuation methodologies to appear and to be well understood.

External factors driving valuations

External factors can always be brought back to supply and demand.

From a supply viewpoint, there are more companies than ever starting to appear with disruptive business models. Dropbox did not exist six years ago, but now has a valuation of approximately $10 billion and expected 2014 revenue of at least $200 million, perhaps closer to $400 million.

But for every Dropbox, there are 100 other companies that won’t make it. How do you pick the next Dropbox? Insider tech investors know you can’t. The investment approach is far more about filtering out those who aren’t going to make it, rather than trying to pick the one company that will.

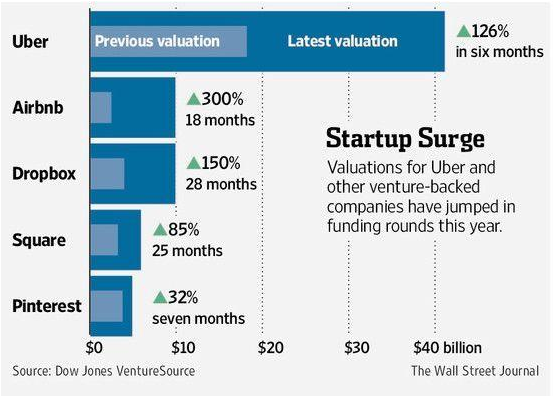

The chart below shows the valuation increments over the last 12 months of major tech companies:

Such incredible valuation changes are driven by two main demand-side factors:

A. Venture capitalists (VCs), in Silicon Valley in particular, are looking for the next Uber (using the current example). They need to invest in just about everything, and once the ‘Uber’ in their portfolio appears they are then looking for a 200 to 400 times return on that investment.

This is generally known as ‘FOMO’ – Fear of Missing Out.

B. The volume of cash now available for early stage investment from VC funds, based on a series of successful exits. This includes the Facebook IPO, LinkedIn, the $6 billion that was part of the WhatsApp deal and a series of other high profile transactions.

It is estimated that last year, Silicon Valley VCs invested approximately $46 billion in early stage ventures. They are looking for between $100 billion and $200 billion back, based on their current investment approach.

Will they get this kind of return? They might. If they do, next time around they will invest $200 billion and look for $400 to $800 billion in return, and so on it goes. At some point the bubble will burst and there will be a correction. It is reasonable to expect there to be a reset of the external factors driving valuation in the next few years.

Internal factors driving valuations

The business model is the primary internal factor driving valuations.

Many people have done a business or accounting course and all of the profit calculations were based on the manufacture and sale of widgets. Even the advent of the services based economy has not shifted this.

To understand the technology based business model, a fundamental shift is required to look at profitability from the viewpoint of the customer, rather than the product. While many industries such as fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and banking have been doing this internally for some time, it is not part of their external reporting to shareholders.

To understand how a technology business model makes money (or to establish if this is the case), these are the main elements:

- Life time value: this is the total value of revenue expected from that customer, over the life time of that customer

- Customer churn: this is what is used as a proxy of how long customers are staying

- Cost of acquisition: what is the total cost of acquiring the customer, which will be a combination of sales and marketing costs

- Cost of retention: an essential part of any business which is based on long trailing revenue streams, including brand building, account management and customer support

- Cost of delivery: for tech based businesses this is minimal, as the platform does all the ‘heavy lifting’

- Cost of running a business: this is the standard office rental, cost of executives or office-holders, investor relations, legal support and other compliance related costs.

This calculates a product yield which is a return on investment for the sunk costs of building the product.

In real estate property management businesses, the accepted valuation method is 3–4 times annual revenue. For tech companies, a multiple of revenue is also used but this has been higher than 10 times for some time.

Why the difference between 3 times and 10+ times? Firstly, the cost of delivery is genuinely minimal, hence the product yield is normally at least 50% of lifetime value. Second, the growth potential if the product is truly scalable, and the founder can find a way to reach the right customers, has no limits as there are no capacity constraints, as evidenced by the rapid global expansion of Uber.

So what’s the best way to approach investments in tech companies, and especially those which are pre-cashflow positive?

- The most effective investors are those who are actively engaged in their portfolio

- The external factors driving valuation are fickle and can change rapidly. There is a ‘herd mentality’ that goes with it. A second opinion is always a good idea

- Remember the ‘inside’ tech investors don’t have a magic formula either to pick the winners – hence this part of your portfolio can only be considered speculative

- Ask questions to get inside the business model. Does the founder know how they will reach their customers? Do they know how much this will cost? What is the likely customer retention and engagement cycle? How long will they take to find out if the idea works? Will the money last?

Tech has had some amazing success stories that grab the headlines, but you hear far less about the massive number of failures. There are 1.2 million apps in the Apple store, but we use only seven each on average. The majority go nowhere. It can be a scary ride that’s not the place for a big chunk of your retirement savings, but it’s also an exciting space to be in.

Rachel White is a partner at corporate advisory firm, Verde Group. This article is for general education purposes and does not address the personal circumstances of any individual.