The traditional distinction between ‘value’ and ‘growth’ investors is too simplistic. Classically, ‘value’ investors aim to generate returns from shares that offer a high yield from current earnings or dividends relative to their prevailing share price, whereas ‘growth’ investors buy shares with superior earnings growth potential. Since rapidly-growing companies are unlikely to be available at bargain prices, the two schools of thought are often considered to be at loggerheads.

Our approach is different. Investing isn’t about putting stocks into boxes. It’s about delivering superior long-term returns relative to the risks taken. When we make our assessment of a stock’s future-return potential, we’re primarily motivated by its intrinsic worth, an appraisal which includes due consideration for the value of future growth (if any). The critical question is whether we can buy a company’s shares for much less than they are truly worth.

Unlikely bedfellows

Viewed through a value/growth lens, Facebook and Peabody Energy would make unlikely bedfellows. How much common ground can there be between the growth-rich business of mining for data and the growth-starved business of mining for coal? Perhaps more than first meets the eye. Dig deeper and it’s evident that there is enormous economic demand for high-quality sources of both coal and data. Both are also targets of popular and regulatory backlash that threatens to restrict supply. And in both cases, we conclude that the prospects are brighter than implied by the current price.

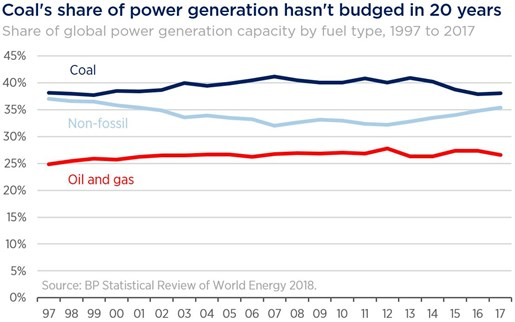

Peabody Energy is the world’s largest publicly-traded non-state-owned pure-play coal miner. Amid all the talk of a shift to cleaner fuel sources like gas and renewables, it’s sobering to note that coal’s share of electricity production was 38% last year – exactly where it was 20 years ago. As global demand for electricity has increased, coal has proved its worth as a cheap and reliable fuel.

Can we do without coal?

That’s not to say coal is without its problems, and the environmental cost of burning coal is well known and beyond dispute. That said, the social cost of not burning coal is not to be ignored either. Consider China, the world’s most populous nation, which accounts for more than 50% of global coal use. Its drastic 2016 directive to cut coal production as part of a project to restore ‘blue skies’ over Beijing proved to be so punitive for households and small businesses that it was relaxed just months later. So as tempting as it may be to say, “let’s stop investing in coal”, the reality is not that simple.

A better solution to the pollution problem needs to consider how coal is used, not just whether it is used. If coal isn’t going away, at least those who rely on it can burn higher quality sources. That’s where producers like Peabody stand to benefit. Its most valuable mines are located in Australia and have been blessed with higher energy-content coal than the Indonesian mines that currently account for most of Chinese thermal coal imports. By gradually switching from Indonesian to Australian coal, the Chinese can generate the same amount of electricity with less coal, thereby releasing fewer pollutants into the air. As a result, Australian mines are struggling to keep up with demand.

But you’d never know that from market sentiment. Among widespread condemnation of coal in general, such differences in quality are often overlooked. Indeed, so out-of-favour has coal become that even the most promising coal projects are finding it hard to obtain approval from regulators or financing from banks.

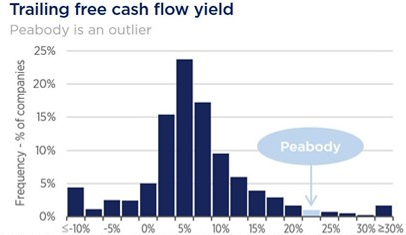

Peabody itself has learned its lessons the hard way. Flying high in the commodity bull market that peaked in 2011, Peabody took on too much debt and found it could not meet its obligations when the price of coal turned south, eventually filing for bankruptcy in April 2016. Investors tend to ‘fight the last war’ and are worried about a repeat. But while Peabody’s operations haven’t changed much since the last peak, its financial position is markedly different. Net debt has fallen from $5.7 billion to zero, capital expenditure is down by almost 75%, and the company has plenty of loss carry-forwards to shield it from future tax. The result? Free cash flow has more than doubled from the last peak, while the company’s enterprise value is down by over 70%. In terms of cash flow yield, Peabody is a true outlier.

The risk, of course, is that Peabody’s present could be much brighter than its future. We think that’s unlikely, but it highlights one challenge of being a contrarian investor: if you are contrarian and wrong, it is generally for reasons that were obvious to everyone else. Lots of people hate coal, and if regulators go for broke and attempt to reduce coal use at any cost, they could hurt Peabody’s fundamental prospects.

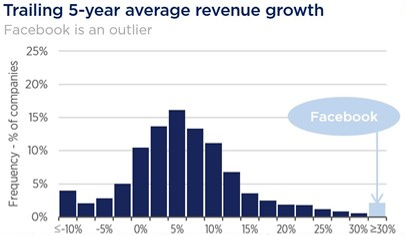

Is Facebook also an outlier?

The graphs below chart the percentage distribution of companies on a trailing 5-year average revenue growth and a trailing 12-month free cash flow yield.

Source: Datastream, Orbis. Statistics are compiled from an internal research database and are subject to subsequent revision due to data cleaning or changes in methodology. Distributions show the percent of stocks in the FTSE World Index (excluding financials) in each bracket. Each value on the x-axis represents the maximum value in the range. Orbis estimate of trailing 12-month free cash flow used for Peabody.

Priced at a multiple that is close to the market average, Facebook is an outlier in a different respect: its growth rate has been spectacular. It too has more than its share of haters, with the Cambridge Analytica fiasco putting personal data squarely in the regulators’ spotlight. But, as with Peabody’s coal, there has been no let-up in demand for Facebook’s services along with its Instagram and WhatsApp properties. Users are still engaging with these platforms as much as they did before the scandal, while advertisers have shown no signs of deserting Facebook en masse.

The revenue that Facebook generates is primarily from advertising services. The company’s ability to deliver more effective and relevant ads, and to therefore charge a premium for them, is unparalleled because of the amount of data it knows on its users. Regulation that seeks to discourage the sharing of this data with third parties would strengthen Facebook’s competitive position, potentially allowing Facebook to capture revenue which previously had to be shared with partners. Meanwhile, the likely regulatory burden of having to identify and block inappropriate content is an exceptionally difficult task, one at which only the companies with the most sophisticated technology, like Facebook’s, will stand a chance of succeeding.

Regulation as a barrier to entry

No doubt increased regulatory scrutiny is a fact of life for both Facebook and Peabody. However, while heavy-handed regulation is often viewed with trepidation by investors, again we take a different view. In our assessment, higher levels of regulation tend to act not as a barrier to corporate success, but as a barrier to competitive entry, and are often beneficial for incumbents’ profitability in the long term.

We believe both Facebook and Peabody offer compelling returns for the long-term investor. Whether the returns are realised via growth or yield, or some combination of the two, is of little consequence: it’s the total return potential that counts for us, and always has been.

It’s true that we usually do a better job in market environments when shares with low expectations have outperformed those that everyone seems most excited about. But ask us if we are value or growth investors and our answer is: neither.

Ben Preston is Portfolio Manager at Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This report constitutes general advice only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.