Before the 2022 Federal election, the Coalition proposed a ‘Super Home Buyer Scheme’ under which people would be allowed to withdraw up to 40% of their superannuation savings, up to a maximum of $50,000, to be devoted towards the purchase of their first home.

Since the 2022 election, the Coalition in Opposition has re-iterated its on-going support for this scheme, with shadow ministers variously suggesting that the $50,000 limit could be increased (Sukkar 2024), or that existing homeowners be allowed to transfer superannuation savings into mortgage offset accounts (Kehoe 2023).

An alternative suggestion, recommended by a Coalition-dominated Parliamentary Committee on Tax and Revenue in 2022, is that first home buyers be allowed to use their superannuation savings as collateral for a housing loan. Although it added that this should be conditional on “implementing policies to increase the supply of housing”.

Proponents of the use of superannuation in any of these ways argue that home ownership status has a bigger impact on a person’s security in retirement than his or her superannuation balance. That is, a person or couple who have attained home ownership and paid off their mortgage before reaching retirement will be in a better financial position than if they hadn’t (Bragg 2024).

Some proponents also argue that housing represents a better investment than superannuation because:

- Returns from residential property have historically been almost the same as those from shares (and higher than those from bonds) with less volatility

- Investment in housing can be more highly geared than investment in other assets

- Owner-occupied housing enjoys more favourable taxation treatment than superannuation

- Owner-occupied housing is exempt from the pension assets test, unlike superannuation savings or other assets

There are, however, four significant problems with policy suggestions of this nature.

1. Inevitably higher house prices

The widespread use of such a scheme in a supply-constrained market like Australia’s would inevitably result in higher housing prices rather than in higher rates of home ownership.

Evidence from past attempts to put additional purchasing power in the hands of would-be home buyers - be they through cash grants, stamp duty concessions, deposit or mortgage guarantees, lower interest rates or easier lending criteria - have all resulted in higher residential property prices without reversing the decline in home ownership rates. This is especially true among people in the age cohorts at which these measures have ostensibly been targeted.

This was the conclusion of the Australian Treasury when it considered a similar proposal in the context of the 1998-99 Budget. It noted that “a superannuation for housing scheme could not be targeted efficiently to those individuals who would not otherwise achieve home ownership before retirement” and that “it would also reduce retirement incomes and national savings” (Australian Government 1998: 2-15).

Even the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue in 2022, which recommended that people be allowed to access superannuation savings to enhance their capacity to purchase housing, acknowledged that “allowing first home buyers to access or borrow against part of their super to purchase a whom would, in the absence of increased housing supply, likely increase demand and lead to higher property prices”.

2. Little value to younger aspiring homebuyers

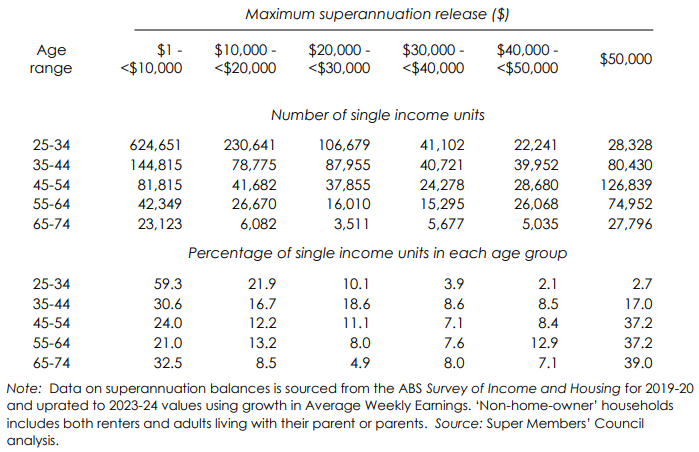

The median superannuation balances of singles and couples aged between 25 and 34 – the archetypal first home buyer cohort – are only $20,300 and $45,200 respectively. This means that the median amounts which they could divert to the purchase of a home would be just over $8,100 and $18,000 respectively.

Again, depending on their incomes – which are highly likely to be lower than those of people in older age groups – this would increase their purchasing capacity by up to $40,500 and $90,000, respectively.

The table below shows that fewer than 3% of single non-homeowners aged between 25 and 34 have superannuation balances large enough to withdraw the maximum amount of $100,000 (combined) allowable under the ‘Super for Housing’ proposal; while more than 78% of single people in this age range would be unable to withdraw more than $20,000.

Similarly, only 5.25% of single non-homeowners aged between 35 and 44 would have superannuation balances large enough to withdraw the maximum amount of $100,000 (combined); while more than 50% of single people in this age range would be unable to withdraw more than $20,000.

Number of single people eligible to withdraw sums within specified ranges under the Coalition’s ‘Super for Housing’ proposal

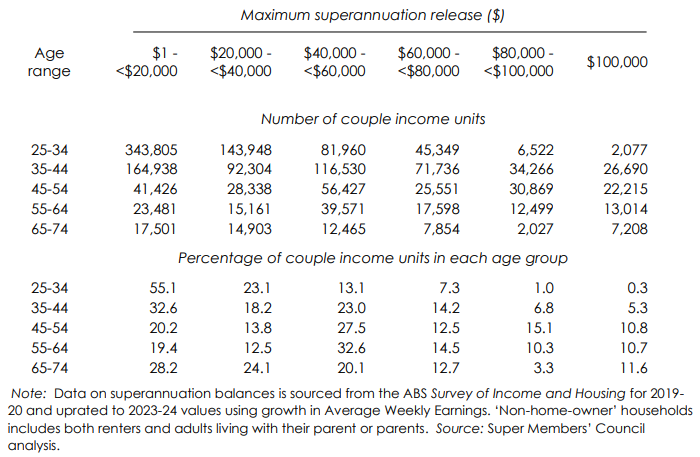

The table below shows the number and percentage of couple non-homeowner households who would be able to withdraw amounts within $20,000 ranges up to the maximum of $100,000 ($50,000 for each member of a couple) under the proposed ‘Super for Housing’ Scheme.

Number of couples eligible to withdraw sums within specified ranges under the Coalition’s ‘Super for Housing’ proposal

In simple terms, ‘Super for Housing’ would do little for the people who need most assistance to become homeowners, and it would do most for those who need it least (over 45s).

3. Loss of retirement income more than offsets savings

Allowing people to draw from their superannuation accounts to purchase housing would inevitably leave them with smaller superannuation balances upon reaching retirement. In most circumstances, under plausible assumptions, the loss of income in retirement would more than offset housing cost savings from earlier entry into home ownership.

Super Members Council (2024c) modelled the impact of the scheme on the lifetime disposable income after housing costs of a hypothetical couple from age 22 until assumed death at age 93 (Super Members Council 2024).

Each member of the couple was assumed to earn their respective median wage for their age and gender whilst working, with the female partner assumed to work part-time between the ages of 29 and 43 in order to care for children, while the male partner is assumed to earn some business income between the ages of 45 and 66. The male partner is assumed to have a starting superannuation balance of $4,000 and the female partner $2,500.

The couple are assumed to rent from age 22 until age 30, when they purchase a median-priced house, two years earlier than they would have done otherwise, assisted by withdrawing a combined $55,000 from their superannuation accounts. Both partners are assumed to retire at age 67, at which point their superannuation assets, having earned an assumed 7.5% pa (after tax but before fees of 58 basis points) during the accumulation phase, are converted to an account-based pension earning 6.5% per annum (before fees) and, together with non-superannuation assets held in the form of term deposits, drawn down at a rate of 10% pa until death at age 93.

The SMC modelling finds that this couple’s disposable income after housing costs over the course of their lifetime is over $165,000 lower (in today’s dollars) than it would have been otherwise – despite attaining home ownership two years sooner than they would otherwise have done.

The couple’s housing equity is $161,900 higher than it would have been otherwise, but this additional wealth is untapped unless they sell their home. Their superannuation assets are $149,000 lower (in today’s dollars) than they would otherwise have been, which under the assumptions above results in their disposable income after housing costs being $107,600 lower during retirement.

Additionally, their lifetime housing costs are $142,200 higher than they would have been otherwise, because of the higher rents paid during the eight years prior to attaining home ownership, and higher stamp duty, mortgage interest and council rates during the period of home ownership (flowing from the scheme’s estimated impact on the general level of residential property prices).

Even if the impact of the proposed scheme on the general level of residential property prices were half what SMC has estimated – i.e. 4.5% rather than 9% - so that the impact on lifetime housing costs is $29,300 (in today’s dollars) rather than $142,200, the hypothetical couple’s lifetime disposable income after housing costs would still be $52,600 less than otherwise.

Alternatively, if it were to be assumed that the hypothetical couple were able to bring forward their entry into home ownership by four years (rather than two), lifetime disposable income would be $87,600 lower than otherwise assuming a 9% increase in the general level of property prices.

4. A significant hole for the Federal Budget

Finally, the proposal to allow people to withdraw accumulated savings from their superannuation accounts in order to finance the purchase of housing is likely to entail a significant cost to the Federal Budget.

That’s because contributions to superannuation funds, and earnings generated by superannuation funds (including capital gains) are subject to income taxation (albeit at lower rates than income in the form of wages and salaries), whereas capital gains on owner-occupied housing are completely exempt from any form of taxation; and because of greater demands on the age pension due to more people reaching retirement age with smaller superannuation savings.

Modelling undertaken by Deloitte for Super Members Council (2024a) suggests that the annual cost to the Federal Budget arising from the scheme proposed by the Coalition would escalate from around $300 million in 2029-30 to $1.3-1.4 billion in the 2040s and 2050s, to almost $8 billion per annum by the 2090s. These shortfalls would need to be made up by tax increases elsewhere, spending cuts or additional borrowings.

Saul Eslake is an economist, consultant, speaker, and the principal of Corinna Economic Advisory. This article in an extract from a research paper commissioned by the Super Members Council.