In life, we frequently conflate symptoms with their underlying causes, leading us to sometimes address the effects and not the actual causes of issues. We see this occurring, for example, when a doctor prescribes a topical medicine with negative side effects to treat a skin condition instead of addressing what may be the root issue — an unhealthy lifestyle and a poor diet. The overall effect of practices such as these might be why the length of the average health-span — the period of life spent in good health — has not kept pace with longer lifespans and is actually falling.

A similar pattern can be observed in today’s financial markets. With index concentrations at historic highs, I often read and hear from active investors that the growth of passive investing is to blame. However, both index concentration and passive ownership reaching all-time highs are the result of the same underlying cause: investor demand for the stocks of companies with massive profit growth.

The cause

All financial asset prices reflect investors’ aggregated expectations of future cash flows. Take equities. While each sector is different, they all generally coalesce around profits, earnings-per-share, net income, free cash flow and what have you. So when a corporation in a large industry manages to capture a disproportionately high share of the profit pool, its stock becomes an outsized proportion of a stock index. We saw this with AT&T, General Motors, IBM and others in the 1950s and 1960s.

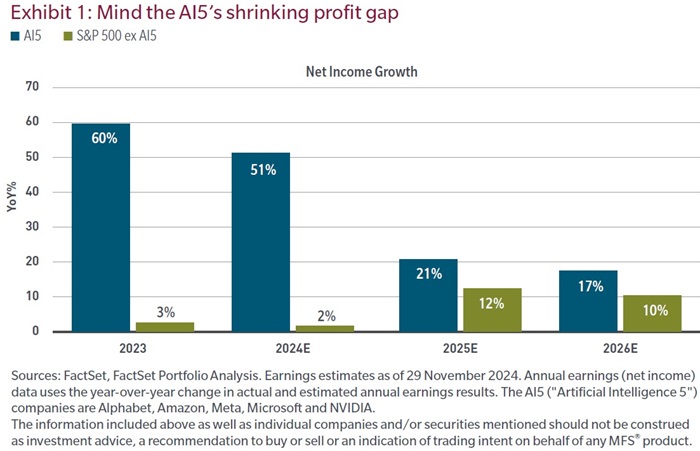

Similarly, today we observe this with mega-cap artificial intelligence stocks, the net income growth expectations of which vastly outpace those of other S&P 500 companies (Exhibit 1). In 2023, the growth expectations of AI stocks were 20 times higher than for those of the rest of the S&P. It’s these profit expectations and differentials that primarily drive their index weightings.

However, index concentration and the resulting share-taking by passive affects the 495 non-AI5 stocks (The 'Artificial Intelligence 5 or AI5' companies are Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Nvidia and Alphabet). Liquidity doesn’t scale, and every dollar pulled away from discretionary portfolios and allocated to nondiscretionary ones places downward pressure on the cost of equity capital for these companies.

So where’s the risk?

Falling net income expectations for the AI companies

Index concentration doesn’t end because passive flows reverse. Any change in stock market concentration, is in fact, a symptom. The cause is a change in profit expectations.

As shown in Exhibit 1, Wall Street analysts have considerably lowered their 2025 and 2026 net income expectations for the AI5. The delta between the two cohorts went from 20x in 2023 to 6x in 2026. While this is still a sizeable gap — and nominal profits for the AI5 are massive — what will matter to stock prices will be the rate of any changes versus what will have been discounted in stock prices.

Volatility is the market adjusting to new information that corrects erroneous assumptions relating to profits. One of the risks to passive investors, or any investor over-indexed to the AI5, is that prices will adjust in line with the downward estimates in analysts’ earnings expectations.

Why the analysts might be right

When a new and broadly applicable technology emerges, supply is low but customer demand is high. The imbalance leads to an outsized return on capital for the first movers. These high returns naturally attract capital, as other entrepreneurs seek a piece of the action. The stock prices of those companies rise too, creating a feedback loop and in effect inviting more entrants into the industry.

Competition rises, bringing supply to the market. But it almost always overshoots and exceeds customer demand. The cycle then begins to reverse: Pricing and returns fall, driving down stock prices.

Overproduction and deflating returns lead to industry consolidation until supply and demand reach equilibrium.

While economics lacks any immutable laws and every cycle is different, the capital cycle has repeated itself throughout history. So while we don’t know when the AI capital cycle will turn from growth to consolidation, we believe it will happen, as it has in the past. We can look back to the 1990s internet bubble for a recent example. We can also go back to the railroads in mid- and late-nineteenth-century England and the United States. And it’s happened with every other technological advance in the past 100 years, from the automobile to the radio to the telephone to the computer.

Software’s evolution

Over the past 30 years, people have bought software to help them complete tasks. Today, AI is changing software from a tool to something that completes tasks on its own. AI agents will combine information retrieval, reasoning capabilities and self-coding to evolve every piece of software and business process.

AI is in the process of redefining SaaS from software as a service to services as a software. As large language models become a commoditized raw material in the software supply chain, it will be AI-based software products that end up improving the functionality of existing software. Companies’ ability to take price will be a function of the customer’s return on the investment.

The vectors of competition in software, AI, and the broader technology landscape are just short of incredible. However, the makers of many existing software applications may experience a massive erosion in pricing power. In my view, given how over-indexed benchmarks are to assets with increasing competition due to the capital cycle, there should be much greater dispersion ahead, causing financial markets to rediscover the merits of active investing.

Conclusion

Investment vehicles, whether active or passive, are just collective pools of capital. While they may influence asset prices in the short term, over the long term it’s the return on capital that drives the terminal value of enterprises, not the flow of capital. As bottom-up fundamental investors, we assess where returns on capital are at risk due to rising competition and where they are durable due to the lack of it.

In this environment, stocks, whether public or private, facing rising competition may find it far more difficult to match profit expectations, bringing forward a different paradigm in the value of portfolio construction.

Robert M. Almeida is a Global Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager at MFS Investment Management. This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It has been prepared without taking into account any personal objectives, financial situation or needs of any specific person. Comments, opinions and analysis are rendered as of the date given and may change without notice due to market conditions and other factors. This article is issued in Australia by MFS International Australia Pty Ltd (ABN 68 607 579 537, AFSL 485343), a sponsor of Firstlinks.

For more articles and papers from MFS, please click here.

Unless otherwise indicated, logos and product and service names are trademarks of MFS® and its affiliates and may be registered in certain countries.