The rise of passive investing over the last decade has been remarkable, and the 'active versus passive' investing debate has intensified. The debate tends to focus on how much of the market is passively managed and less so on the capital flows i.e. who is buying the stock of companies and why? When stocks are being purchased without any thought to the underlying fundamentals of the company, this could create a risk to how markets operate.

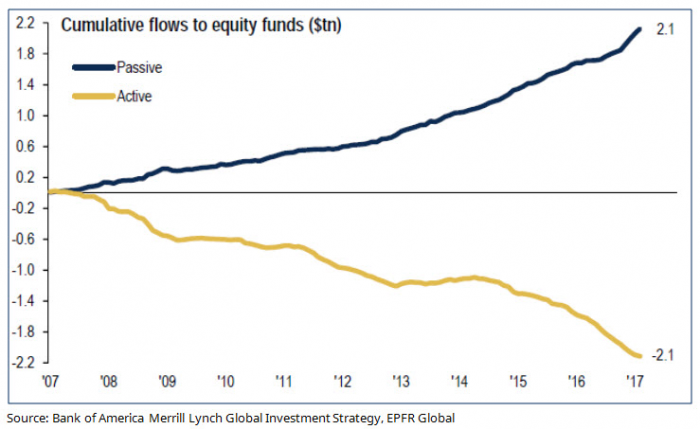

Since 2007, cumulative flows into passive equity vehicles (which ignores segregated institutional accounts) have been US$2.1 trillion, offset by similar outflows from active vehicles. Passive exposure of the total market is estimated at circa 40% globally, and predicted to rise to as much as 60% over the next five years (Deutsche Bank, 25 May 2017). These numbers would be higher if we accounted for ‘quasi’ passive flows from non-market cap based index type strategies (including ‘factor’ portfolios).

Passive vs active equity flows since 2007

There is clearly a benefit of low management costs that accrues to those using passive (or semi-passive) strategies. However, at what point are the benefits of low management costs outweighed by the causative effects of very large flows of capital being allocated with no reference to economic return. Is there a ‘paradox of passive’ so that investors have low management costs but in aggregate lower returns or higher risks? As more capital is invested with no thought behind what is being purchased, there has to be a tipping point where this irrational behaviour is no longer sustainable. When is that tipping point? We would suggest we are close to or even past the tipping point in some markets.

While the case for passive investing rests largely on the low cost (the SPDR S&P500 ETF, the largest in the world, has an expense ratio of just nine basis points, while the Vanguard total US market ETF is four basis points), investors in these strategies would do well to remember a number of points.

Value does not equal price

Passive (and semi-passive) approaches ignore value and price (and governance, capital management, etc) as they invest on one criteria alone, which is the methodology for the construction of the index, often market capitalisation, or close to it. This creates a somewhat perverse outcome as the larger a company becomes, the greater the proportion of new money it receives. The indices on which passive investments are made, or indeed any rules-based approach, are prone to distortion.

Passive investing does not create the distortion in itself, if the index is an accurate reflection of market efficiency in capital allocation. However, if there is a distortion already or there are sufficient flows into a subsector of that index (e.g. a style or sector bias) then passive flows will amplify that distortion.

This process of correcting distortions is generally held in check by other non-passive (or active) investors, only to the extent those non-passive investors are influencing the price. That is not the case today with non-passive investors being large net sellers and passive investors being large net buyers. The distortions are complicated by non-market-cap based index investors biasing certain stocks.

Consider for example Amazon (AMZN), the market’s consumer discretionary darling of the moment and the third largest stock in the S&P500 at 1.9%. The stock has risen 40% this year (versus S&P’s 17.7%). It has a market cap of US$475 billion, up from US$114 billion at the end of 2012 despite poor fundamentals, a P/E ratio of over 200 times and never paying a dividend. However, it sits in at least 176 ETFs and is a top 15 holding in 117 of those.

The net result of this is that while the stock has a 1.9% market cap weight, the ‘size based weight’ of all the ETFs in which Amazon is listed is 2.7%. For every $1 of flow into these ETFs, Amazon receives 150% of its market cap based weight of flow. And based on filings in the US over the last 12 months, the top three passive managers have been buyers while the top five active managers have been sellers.

The risk is that if passive flows continue at their current rate, Amazon gets even more expensive, active managers underperform, passive flows get a further boost and we have a (not very) virtuous cycle.

It is flow that counts

Passive exposures are still low, despite what is conceivable, but it is flows that cause prices to move, not ‘stock’, and these are massive. For the share registers of the top 15 stocks in the US, the dollar-weighted trading volume by grouping has been similar to the Amazon analysis with 'owners' and active managers net sellers, and passive managers, net buyers.

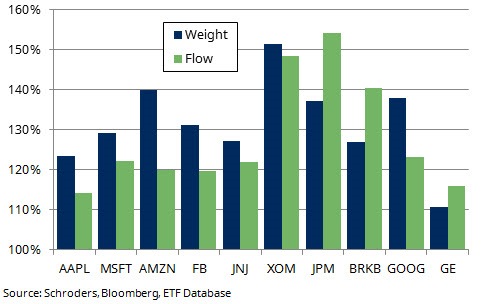

One method of analysing the distortions created by passive and other rules-based investment methods is to examine the weight of a stock in these indices and to compare it to its market cap weight.

To do this, we weight each component of the ETF by the aggregate dollar value in that ETF and compare the addition of these to the market cap weight. If the dollar-weighted value of the ETF holdings is greater than the market-cap weight then these passive strategies are collectively contributing to an overweighting in these stocks. We can examine this in terms of current invested dollars to gauge the impact of historical flows and in terms of recent flows. This is shown in the next chart.

Percentage of ETF weight/flow received relative to market cap weight/flow in 12 months to 6 June 2017

Every stock in the top 10 of the S&P 500 has received a significantly greater proportion of passive flow than its market share in the S&P500 would suggest. Their aggregate weights in all the ETFs far exceeds each stock’s market-cap weight in the broad market index. For example, the average dollar-weighted value of Amazon in all ETFs adds up to 140% of its market-cap weight, implying that the historical flows into these ETFs has been at a rate 40% greater than its market cap would justify. Similarly, the dollar-weighted value of the flows into Amazon has been 20% greater than its market cap would justify.

Total portfolios can’t be passive

Virtually no investors have a total portfolio that is truly passive. While Warren Buffet’s estate might be largely passive in that inflows and outflows are dwarfed by the size of the corpus, the rest of us do not really have that luxury. Cash flows in and out mean that almost all investors have an active approach to their overall investment strategy. A low-cost strategy makes sense but investors should have regard to the way these pieces fit together, with some understanding and management of the components.

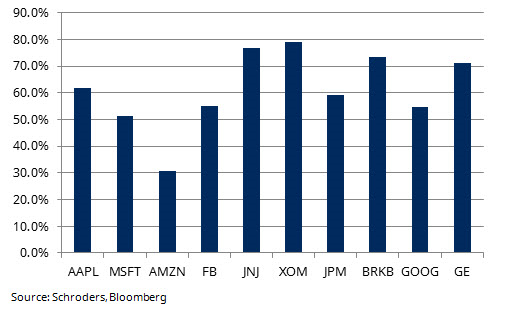

As the proportion of passive investment grows, the rigour applied in terms of governance and other issues is reduced. How often do passive, or other rules-based strategies, vote against management? It’s an issue when passive investors are the largest holdings of these major companies.

Percentage of the top 10 shareholders that are passive (as at 31st March 2017)

Conclusion

While we understand and generally concur with the desire to implement portfolios cheaply, investors should be cognisant of what they are buying. It is our view that the flows into passive and quasi-passive vehicles are having a distortive effect on markets at the moment and this is always prone to sudden reversals. Just as investors have jumped on the cheap bandwagon, the paradox of passive investing is that it could turn out to be an expensive mistake.

Greg Cooper is CEO of Schroders Australia and Global Head of Institutional. Opinions and projections in this article constitute the judgement of the author as of the date of writing. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any member of the Schroders Group and are subject to change without notice.