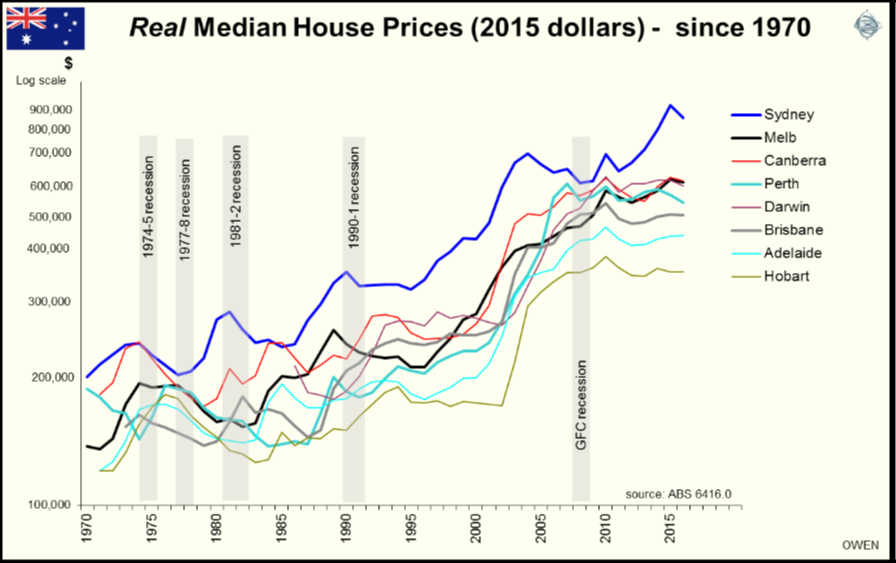

House prices in Australia suffered only about half of the declines seen in the United States during the GFC. They then resumed their climb in 2012, fuelled by cheap debt courtesy of 12 interest rate cuts by the Reserve Bank of Australia since November 2011.

The chart below shows real house prices (i.e. after inflation) in the major capital cities over the past 45 years.

Prices have fallen in each of the major economic contractions, but have generally moved steadily upward for more than a century. Growth in house prices has been driven largely by steady population growth (mostly from immigration) in each of our main cities, a feature that is unique in the world.

Rises softening but support remains

House prices have started to soften in all the major markets over the past year. The local economy is heading for a slowdown with the end of the mining boom and the upcoming end of the housing construction boom, but there are several factors that should provide some support for house prices:

- Interest rates are low and more cuts are on the horizon

- Banks remain keen to lend for housing (but little else)

- There is a seemingly never-ending flood of cashed-up immigrants (and locals) looking to buy here

- Little risk of high unemployment (eg above 10%) for a while

- Potential changes to superannuation rules may encourage more investment in the family home, which is likely to remain free from capital gains tax.

The high rise apartment market, however, is another story altogether. In the coming year or so we will probably see many thousands of high rise unit buyers in Melbourne and Brisbane lose money as they struggle to obtain finance to complete their purchases at boom-time prices.

US housing – recovery on track

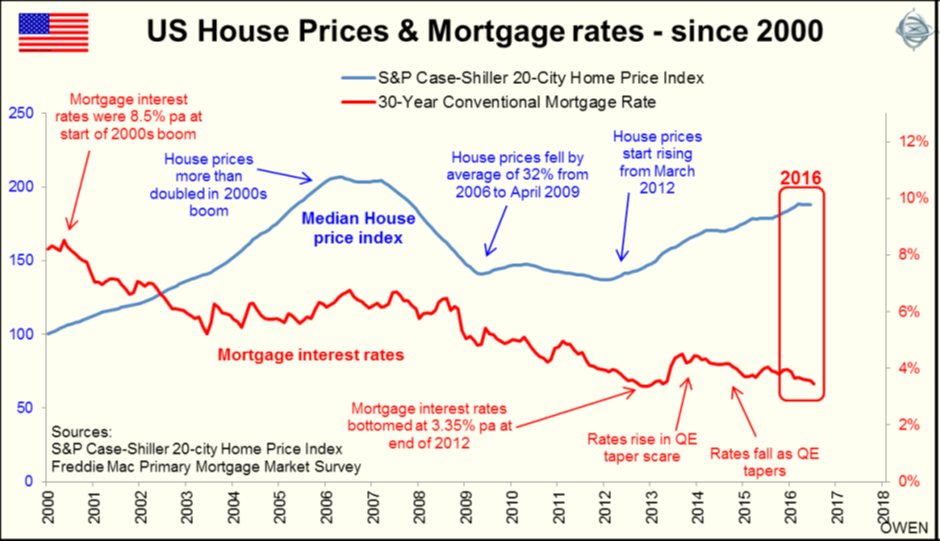

Readers often ask why I pay so much attention to bond markets. One reason is that they are critical to the US housing market (unlike in Australia) and that in turn is an important driver of the US economy, which is still the engine of world growth and investment markets.

The US housing finance bubble was the underlying cause of the ‘sub-prime’ crisis that triggered the deepest US and global recession since the depression of the 1930s. It is also central to US economic recovery. House prices across the US more than doubled during the 2000s boom but then crashed by more than one third on average in the bust, with many cities suffering declines of 60% or more. Prices have been recovering steadily since early 2012. The key has been mortgage interest rates, which have come down from 8.5% in 2000 to below 4% since 2012.

Most Australian mortgage interest rates are variable and driven by short-term interest rates, so mortgage borrowers here are directly hurt by cash rate hikes. But the US market is different. Most US mortgage rates are fixed for up to 30 years and linked to long-term bond yields.

Because of this, as the Fed raises short-term rates in the coming years, long-term bond yields (and with them mortgage interest rates) may stay relatively low. Even when economic growth and inflation rates do rise (which they surely will in time), there is a good chance that each Fed rate hike will dampen expectations of future inflation and work to keep long yields relatively low.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at independent advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities.