Everyone loves winners. Popularity and perceptions of skill in investment normally correlate closely with recent investment experience. What the wise do in the beginning the fool does in the end. We know cycles and bubbles are driven by human behaviour, yet no-one is ever keen to believe they might be the fool.

The past decade or so has been extremely abnormal. Efforts to avert financial crisis morphed into an era of crazily low interest rates and unprecedented monetary intervention. The price corrections and wealth redistribution (away from the wealthy) which financial crises normally accomplish were averted. Unsurprisingly, when taught that speculation and aggressive financial leverage have no cost and potentially large gains, they are embraced. These behaviours impacted the equity market unevenly. Growth, quality, technology, cloud, green energy – an endless stream of thematics and characteristics were fuelled by money growing at a rate faster than the real economy could productively use it.

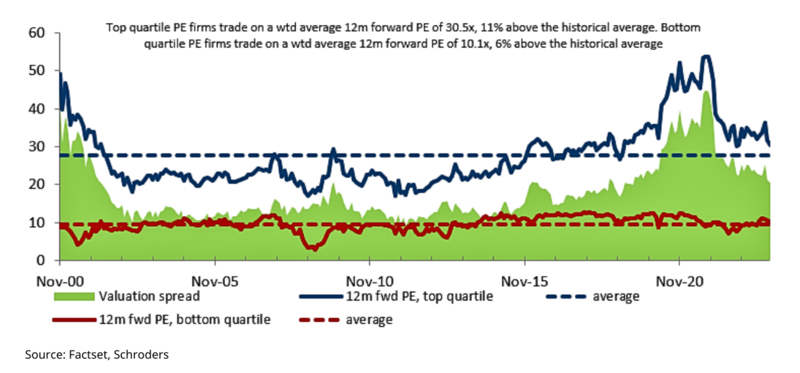

In a valuation context, this saw the valuations of the popular grow at a rate far beyond the more pedestrian. To the surprise of many, including us, the savaging of the real economy induced by COVID-19 at the end of this extended period saw this heighten further, highlighting the often disconnected real and financial economies.

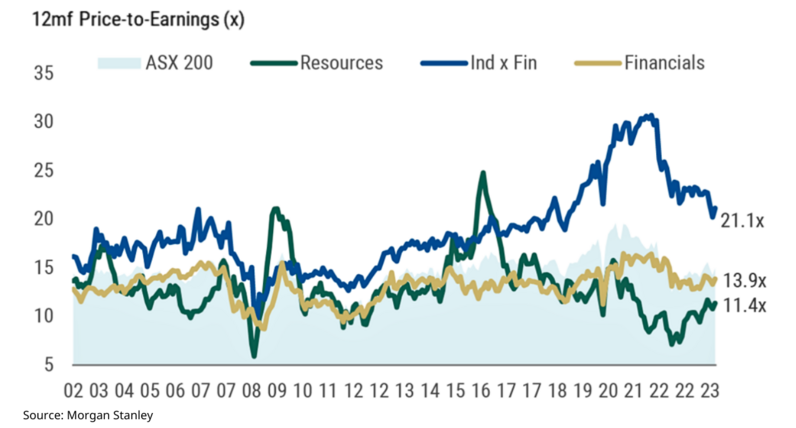

While the return of inflation and the necessity of higher rates has dented this enthusiasm, the valuations of the popular remain sharply above long-term averages, while the pedestrian have retained their reputation. High growth, high levels of profitability and low capital intensity remains the potent cocktail for high valuations.

Like Australian housing, long track records of exceptional returns are seen to reinforce the likelihood of continuation rather than depressing the likelihood of future returns due to highly unattractive entry prices. As staunch believers in the importance of valuation and entry price as important drivers of future investment returns, it is these businesses in the extremely popular category which we believe will be crucial to future returns. Just not in the way most people think.

Returning to more normal levels of interest rates, acknowledging a world which is highly indebted and therefore low growth means accepting more pedestrian returns than have been earned through the ‘free money’ era. It is highly unlikely this path will be smooth, as learned behaviours will not be discarded easily.

Recent market performance in both Australia and the US has again seen performance concentrate around market darlings and technology thematics. Valuations suggest future returns should be far better in embracing the pedestrian and sensible. As history has shown in episodes such as the TMT bubble in 1999-2000, the payback period for being late to the party can be long.

A transition to higher energy prices

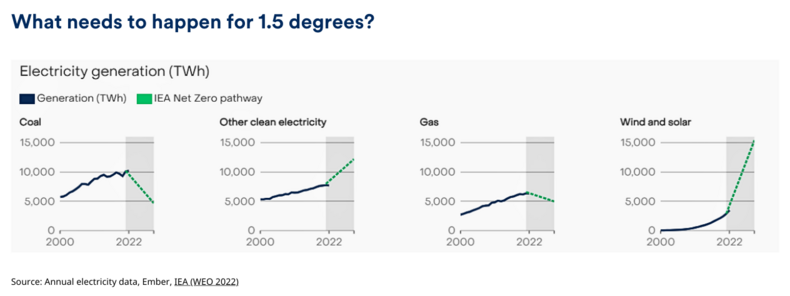

At a thematic level, the pervasive impact of demographics and decarbonisation is indisputable. We expect decarbonisation, in particular, will be a vital driver of future investment returns, though not perhaps in the ways many expect. The appetite for investing heavily in the costly infrastructure on which we all rely is always high until it comes to paying for it. Having become accustomed to egregious road tolls, airport taxes and ever escalating fees for education and healthcare it should be evident that falling prices are not the norm, particularly where construction or services requires high-cost domestic labour. In this light, we find the extent to which the population has come to expect the energy transition can be achieved without sharp changes in energy pricing startling. A couple of basic issues should be obvious:

- We are early in the decarbonisation process and the future path will require accelerating spend

- Fully costed (including the required backup of intermittent power) renewable energy is not cheaper and countries with more renewable energy do not have cheaper prices

Numbers in the vicinity of $300 billion have been put forward as rough estimates of the cost of decarbonising electricity generation and the grid. Assuming we need a long-term return between 5% and 10% to justify this investment, we need to find operating earnings of $15-$30 billion.

The debate on the future of Origin Energy, together with the promised investment by former takeover suitor Brookfield in renewable energy, highlights these issues. Ignoring for a minute the value of APLNG (one of a number of large and perhaps ill-considered LNG investments to export Australia’s East Coast gas resources) and its investment in the low cost and highly successful technology deployed by Octopus Energy, the remainder of the value of Origin lies in its customer base and existing power generation fleet.

The retail and power generation operations of Origin and AGL provide the majority of energy consumed in Australia. The operating profit pool attached to these operations has generally been well under $2 billion. Valuing a retail customer at around $1000 requires a profit per customer of perhaps $75, a skinny and volatile margin on household energy spend. Removing this value for the systems, workforce and complexity in ensuring power is delivered to households leaves the value for power generation. The residual profit pool barely provides a return on written down investments in gas peaking plants and the still necessary but unpopular investments in fossil fuel generation let alone incentivising more investment.

Wind and solar investments are financially and operationally struggling globally and require higher prices. If the government chooses to pretend the investment can be achieved without raising energy prices and tries to extinguish the profit of current operators, private investment should disappear. Socialising costs under the guise of government spending merely sees the costs appear as higher taxes rather than higher energy prices. Decarbonisation is costly and requires profits to incentivise it. The investment, engineering and construction capability will eventually appear if there is money to be made. Workers will follow the money. The profits which will necessarily be sacrificed to fund decarbonisation will need to be found elsewhere in the economy. They are more likely to be found where they are currently fat rather than where they’re lean.

Bullish for mining

The global perspective on the energy transition is inextricably linked to mining, a sector on which the equity market outlook significantly rests, and one on which we remain positive.

The deglobalisation theme has emerged as Western economies react to the realisation of their dependence on Chinese and Asian manufacturing capability. Globalisation flourished courtesy of the cheap labour and lower environmental and safety standards in China and other parts of Asia. Any reversal will require higher prices. Whether subsidies are in the guise of an ‘Inflation Reduction Act’, regulation or tariffs, the outcome should be the same.

As the building blocks of all economies are greatly amplified by the challenge of substituting vast quantities of hard metals for the prodigious (and not yet falling) quantities of fossil fuel consumption in the energy production process, metals demand should be strong unless appetite for decarbonisation spend collapses. Even then, spend which should arguably be diverted to adaptation and resilience spend should still be positive for commodities. The pattern of selling commodities aggressively on the expectation of declining demand in the face of higher interest rates and economic slowdown is one of copying historic patterns. Even if history repeats in the short-term, we believe the reasons for greater optimism in the medium term are strong.

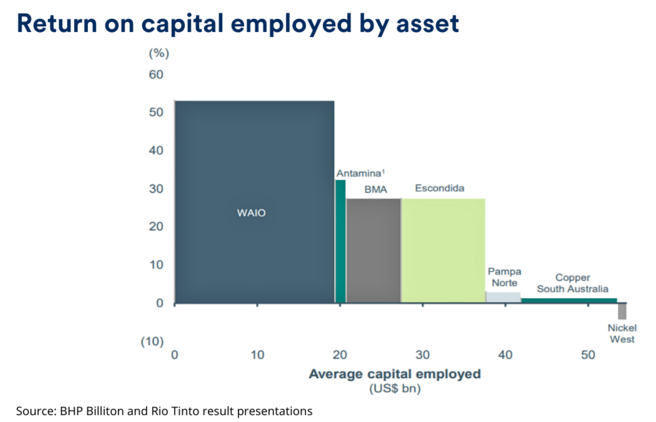

Inventory levels and supply are not indicative of impending price collapse. Most commodity prices, with the probable exception of iron ore, do not appear elevated versus cost curves and the likely costs of new supply. Longer term commodity and goods prices have bifurcated depending on whether China is a producer or a consumer. The iron ore which China has ravenously consumed and had to import has been pushed higher for longer. The rare earths for which China is the major producer or the aluminium which they use cheap and subsidised power to produce, have been depressed.

The sharply divergent experience is evident in results. Returns are low outside iron ore, while iron ore returns, though high, reflect the fact BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto are the lowest cost suppliers in the industry. Western economies claim to be keen to address globalisation, however, when it comes to permitting new mines and coping with environmental impact of chemical and processing plants, the NIMBY effect will be tough to overcome. This should remain very supportive for assets already in place.

Real assets for a new regime

Apparently smooth seas disguising far more turbulence underwater, characterise both economies and equity markets - underlying our cautious outlook. Whilst there is every possibility inflation abates and interest rates stabilise and potentially retrace to some degree over the coming year or two, our expectation is for a return to more ‘normal’ historical interest rate levels rather than the extremes seen since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08.

The side effects of ‘free money’ are becoming painfully obvious. This ‘adjustment’ back to a level at which debt holders expect at least some compensation for lending money to consumers, businesses or government seems unlikely to occur quickly and painlessly.

Starting valuations, or the price paid for an investment, remain vital to future investment returns, and that starting point remains above historic averages for most listed equities. There are exceptions of course, and valuations are further complicated by often cyclical underlying earnings streams, particularly in resources. Nevertheless, when taken as a whole, earnings forecasts for coming years are neither anticipating unusual headwinds nor expecting much change in the pool of corporate profits and how it is currently split. With government and consumer debt, house prices and inequality closer to extremes than averages, an oasis of calm in the future is not our base case scenario.

Martin Conlon is Head of Australian Equities at Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article does not contain and should not be taken as containing any financial product advice or financial product recommendations. It does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.