Who hasn’t wanted to be Biff Tannen in the 1980s cult classic movie, Back to the Future Part II?

As an old man in 2015, Biff discovers Grays Sports Almanac. It shows the outcome of every sporting event from 1950 to 2000. Biff hops in the DeLorean time machine and travels back to 1955. He gives the magazine to his young self. Young Biff places bets on sporting events listed in the Almanac. He quickly builds his evil financial empire from the guaranteed profits.

This doomsday timeline is only extinguished by Marty McFly and Doc going back in time to steal the Almanac from Young Biff, masterfully aided by Marty’s hoverboard from the future. (An aside: thanks Mattel for not delivering on that promised future tech by 2015!). Marty then eventually burns the Almanac, much to the collective sigh of sports betting fans everywhere.

An investor’s dream

What if you had an Almanac for the share market?

That’s what US based investment group Alpha Architect took a look at a few years ago. In their study, they looked at the question: “What if you had perfect (God-like) foresight and knew exactly which stocks would be the best and worst performers over the next 5 years?”.

Their conclusion: Even God would get fired as an active investor.

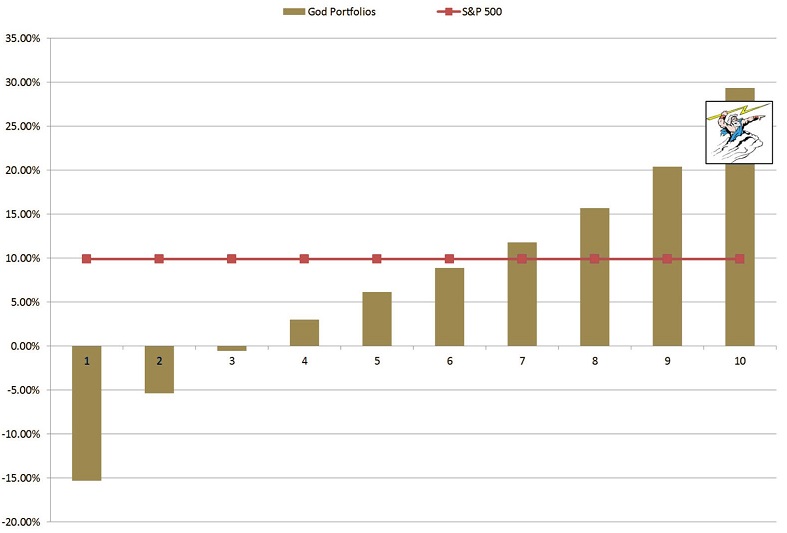

CAGR by ranking decile (1927 to 2016)

Source: Alpha Architect.

The chart above shows the outcome of having God-like skills and investing in the top-performing 10% of US stocks over every 5-year period since 1927. In terms of performance, you would have knocked it out of the park, returning just shy of 30% per annum. Eat your heart out Warren Buffett.

Dramatic drawdowns

But there is a catch.

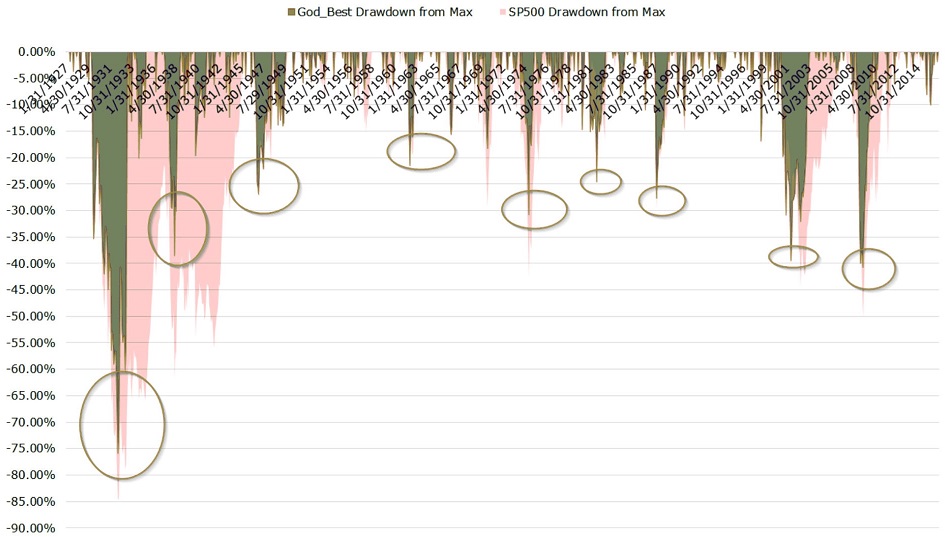

As you can see in the chart below, to get that 30% per annum return, investors in the hypothetical ‘perfect’ long-term active share fund would have suffered extreme gut-wrenching drawdowns (peak-to-trough falls).

Source: Alpha Architect.

Between 1929 and 1932, the fund would have lost nearly 76% of its value before staging a recovery. Drawdowns of -20% to -40% were routine, including 40% falls during the GFC and the 2000’s tech-wreck.

How does this happen? Because even the best stocks don’t go up in a straight line over the long term. The share market is a volatile place, even if God is picking the stocks.

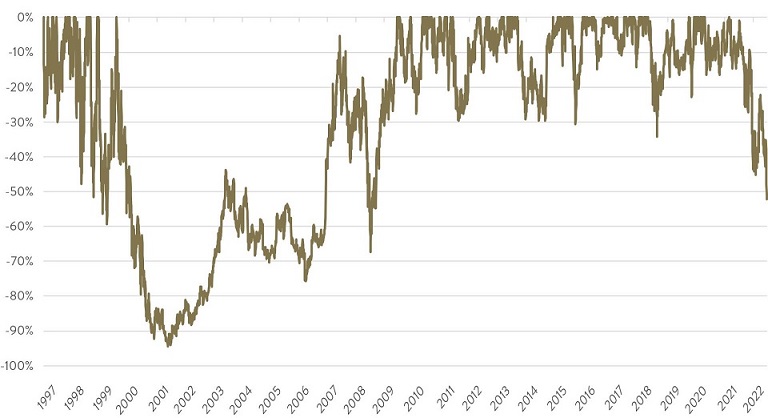

The spectacular success story of Amazon is a prime example. It has returned over +119,873%, or over 32% per annum, since listing in 1997. Yet its share price fell 94% in 2001. It took 10 years to recoup that loss. During that decade, it suffered falls of 45% in 2005, 63% in 2008, and also fell 34% in 2018. It is currently down 52%.

The lesson is that even if you possess godlike skills, you can’t avoid big drawdowns.

Amazon share price drawdown

Source: Factset

The danger of focusing on short-term fund manager performance

This has serious implications for how investors judge performance. High-performing active fund managers don’t post strong returns or outperformance day in, day out. Or even year in, year out. They suffer drawdowns and periods of underperformance.

Investors, therefore, need to back the long-term track record of their fund manager through the shorter-term volatility. If they don’t, they risk jumping from manager to manager and missing the inevitable rebound from skilful managers – and long-term outperformance.

(For our suggestions of what to look for in a fund manager instead, please read our Investment Strategy notes on the topic here and here.)

Myopic investors can drive fund managers to focus short term

If enough investors pull their money when short performance falls, they are ultimately incentivising the fund manager to focus on short-term performance too.

Most share funds disclose that the minimum investment time horizon for their fund is 5+ years. Industry investor funds flow data, however, suggests many investors don’t wait around that long for a fund manager to recover if they are suffering a significant drawdown. In that scenario, even some of the top performing fund managers can be fired. The natural consequence is managers are focussed on the short term and ensuring portfolio company results keep beating short-term expectations.

Shares, however, are a long-term asset class. They benefit from the ingenuity of businesses in raising productivity, creating new products or services, or improving existing ones. This takes time, often at least 3-5 years.

This has led to CEOs the world over lamenting how fund managers are so intently focussed on the next quarterly result, whilst they are generally focussed on setting and implementing business strategy for the next 3-5+ years. We have seen this too, many times over the years. Our response is unless investors’ time horizons become longer in their decision making, then fund managers are unlikely to focus more exclusively on the long term too.

Why investors need to understand their fund’s investment horizons

As we have seen, even a fund manager with perfect ‘God-like’ foresight would suffer major short-term falls. Investors need to accept the best-performing funds over the long-term can also post significant drawdowns.

It is terribly damaging for fund managers if lots of investors redeem during tough times. This is magnified for small caps. Fund managers have to sell less-liquid companies at fire sale prices to fund these investor withdrawals.

Sometimes, of course, investors are justified in withdrawing their capital. But short-term declines shouldn’t be one of those reasons.

Investors need to understand the investment horizon for the fund, and ensure they are aligned with that horizon. Long-term investors are one of the most valuable assets a fund manager can possess. At Ophir, we deeply value ours.

Andrew Mitchell is Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Read more articles and papers from Ophir here.