“Even well-meaning gatekeepers slow innovation. When a platform is self-service, even the improbable ideas can get tried, because there’s no expert gatekeeper ready to say ‘that will never work!’ And guess what – many of those improbable ideas do work, and society is the beneficiary of that diversity. I see the elimination of gatekeepers everywhere.”

Jeff Bezos, quoted in The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, page 315.

“Spend the vast majority of your time thinking about product and platform. Many large, successful companies started with the following:

- They solved a problem in a novel way.

- They used that solution to grow and spread quickly.

- That success was based largely on their product.

In the Internet Century, all companies have the opportunity to apply technology to solve big problems in new ways … if you focus on your competition, you will never deliver anything truly innovative.”

Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google from 2001 to 2011, quoted in How Google Works, pages 91-93.

--------

I recently read 'The Everything Store', 'How Google Works', and Walter Isaacson's biography of Steve Jobs and Apple. The creation of these three extraordinary companies in a short time from the vision of a few individuals left a nagging question in my mind at almost every page: can any company do to the Australian wealth management industry what Amazon did to Borders, what Apple did to Nokia, what Google did to all other search businesses? They are all remarkable stories of redefining how business is done, breaking the traditional rules and in the process, destroying much of their competition.

Markets where anything seems possible

It’s the same with Uber, the ride-sharing service with operations in 53 countries and a market value of about US$40 billion. There are 5,500 taxi licences in Sydney worth about $400,000 each or $2.2 billion. In Melbourne, metro licences have fallen in value from $515,000 a few years ago to $290,000 on a combination of new licences and Uber drivers given access to the market. Uber has fought legal battles all over the world, as it is in NSW, but there’s no denying the public demand.

It’s a good example of a change in the way the global economy operates. It’s a platform business that matches customers with drivers, turning employees into ‘entrepreneurs’, in a similar way to the thousands of businesses run from home using ebay as a distribution platform. And there are ‘ubers’ for all types of services such as cleaning and massage, and of course human resources with sites like Freelancer and Elance.

Amazon is portrayed in the book as a brutal competitor. When diapers.com (owned by a company called Quidsi) was gaining market share among mothers but refusing a takeover offer, Amazon reduced the price of diapers by 30%, and then launched a new service called Amazon Mom, with additional discounts. Quidsi executives estimated that Amazon lost $100 million in three months on diapers. Then Wal-Mart made a bid for Quidsi, and Amazon threatened to drive prices to zero if Wal-Mart won the bidding. The diapers.com founders sold to Amazon out of fear.

“The money-losing Amazon Mom program was obviously introduced to dead-end Diapers.com and force a sale, and if anyone had any doubts about that, those doubts were quickly dispelled with by Amazon’s subsequent actions. A month after it announced the acquisition of Quidsi, Amazon closed the program to new members.” The Everything Store, page 299.

Of course, the Federal Trade Commission investigated the deal but gave its approval. If Amazon and Uber can take such actions in the face of legal hostility, anything seems possible in the age of the internet.

Australia has its home-grown examples of severe market disruption, the most public being the turmoil created for newspapers from the success of realestate.com.au, seek.com.au and carsales.com.au, almost bringing the once mighty Fairfax to its knees.

Unlike Facebook and Twitter which have invented new ‘social media’ activities, companies like Uber and Amazon are killing off competitors. When Jeff Bezos convinced publishers to allow him to put their books on the Kindle, they thought he would charge a margin over the usual wholesale price of books of around $16. But by retailing books online for $9.99, Amazon reinvented the price point. It did not take long for booksellers like Borders and Angus & Robertson to go out of business. Despite the fact that Amazon made a loss in 2014, the market has spoken: its market cap is about USD170 billion.

The defining characteristic of these great American companies moving into retailing, mobile communications, social media, search, taxis, employing contractors and booking B&Bs is that they break the mould for the way business is done. New methods are often not appreciated by the incumbents until it is too late, and it is fanciful to predict what future disruptions will occur. When Mark Zuckerberg developed Facebook, he did not have a notion that it would become the way a billion people shared their most intimate secrets, and he certainly he had no idea how to make money from it.

What is major disruption in Australian wealth management?

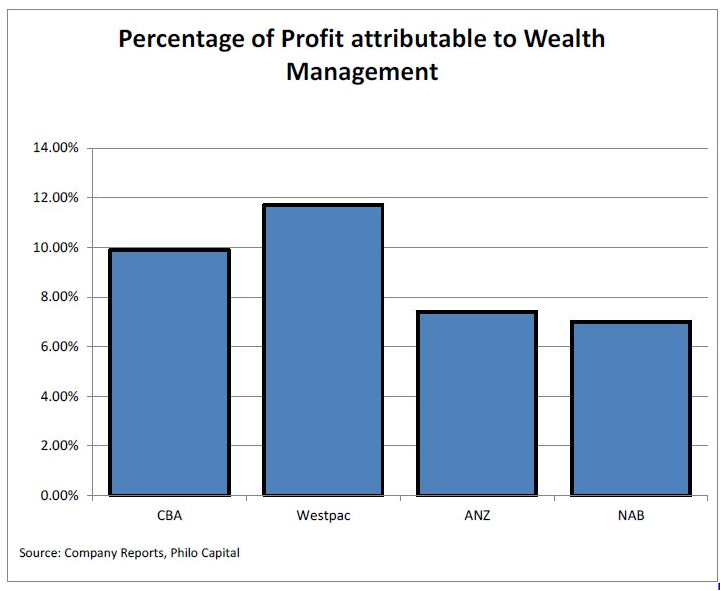

By disruption, I don’t mean somebody developing an online ‘robo-advice’ model (such as GuidedChoice, eMoney, Betterment and Wealthfront in the US or Stockspot and BigFuture in Australia) and collecting $1 billion in funds in a few years, although that would be considered a great success and will happen. With $2 trillion in superannuation, real disruption is at least $100 billion within a few years, which is only 5% of the market. Such numbers would worry the four major Australian banks, which are not only almost 30% of the market capitalisation of the ASX200, but wealth management is significant to them all. They also control the majority of financial advisers in Australia.

Where can disruption happen in the value chain?

Wealth management is usually broken into at least three parts:

- financial advice

- administration platforms

- asset management

Let’s consider what happens if an investor uses a platform such as Colonial First State’s (CFS) FirstChoice Wholesale, the most popular among financial advisers. It requires a minimum of only $5,000 so it is a retail product. On a typical and popular fund such as the Schroder Australian Equity Fund, CFS charges a fee of 1.02%, and splits it with Schroder. Call it 0.5% for CFS administration and 0.5% for Schroder asset management. CFS also has an Australian share index option for only 0.40%, where the asset management costs only a couple of basis points (0.02%). So we can generalise that major platform administration costs about 0.4%-0.5% with asset management on top of that. Financial advice costs are additional: it may be fee for service, say $350 an hour, or a percentage of funds, say 0.5%.

In simple terms, there’s the Australian wealth management value chain. If a market disruptor comes in, they can easily remove the asset management cost by using index funds; they can automate advice based on an internet-based, self-service model; and investments can sit on a simple and inexpensive administration platform. Would it be the equivalent of Amazon charging $9.99 for a book that previously retailed for $30, and destroying other booksellers?

I’m not looking here for the disruption of SMSFs holding $600 billion or one-third of all super. They are serviced by thousands of advisers, accountants and administrators as well as being users of the products of major banks, fund managers and the ASX. My focus here is on a single company coming in with a game-changing, disruptive product offering.

What will the disruptor do or look like?

1. It will not attack one part of the value chain, it will be end-to-end with a complete investment solution. For example, it will not be sufficient to only offer ‘great asset management’, as plenty of companies claim that. A disruptor could hardly ‘out-Vanguard’ Vanguard (or State Street or BetaShares) and provide cheaper and better asset management through ETFs. Broad-based domestic or global equity portfolios can already have negligible costs, less than 0.1%. These ETF providers are successful, well-capitalised companies with overseas parents or partners who already have the capacity to take large shares of the Australian market. Although their growth has been impressive, they only have $15 billion, less than 10% of the money managed by CFS.

2. It will be price-led. I cannot see how anyone can convince enough people that a superior product is worth paying up for because that will depend on a promise (guarantee) of outperformance over time. Amazon can set up systems to deliver a book next day and Telstra can have the best phone coverage in Australia but nobody can promise to outperform the market consistently, whatever their resources. This 'game-changer' will be index-based or with some type of 'beta' engine, not a bunch of superb stock pickers making company visits all day. They are too expensive.

Similarly, the portfolio will not include alternatives or unlisted investments, as they have higher fees and are more expensive to manage, even if done internally. The portfolio is likely to be dominated by cash and term deposits where the ‘fees’ can be hidden in the product margin.

(Of course, Apple's success is far from price-led, its phones are the most expensive on the market. They have achieved this through beauty of design and creating massive desirability and arguably the best product. But in my wildest dreams I cannot see people queuing up around the corner to invest in a managed fund based on its beauty and desirability).

3. It will need to be well-capitalised and carry a great deal of market trust. This is not like buying a book with a secure credit card charging system. People will be handing over their future, their life savings, and the company must be beyond reproach. Whatever they do, they will need to buy time and spend a lot of money on marketing and disrupting and delivering results, plus ongoing R&D specifically for the Australian market.

4. It will be technology-based and self-service. Investors will input their own characteristics into an engine and it will recommend a portfolio of investments, selected according to the risk appetite and demographics of the client. This ‘robo-advice’ (a large part of 'fintech') is already being embraced by major players in the US, such as Charles Schwab and Fidelity’s acquisition of eMoney.

5. It must break established distribution networks. An estimated 70% of financial advisers are already ‘tied’ to the four major banks, AMP and IOOF. At the moment, eight out of every ten people default to the super fund selected by their employer and $10 billion a year automatically flows into default super funds. Whereas everyone selects their own phone, most people do not engage with their superannuation.

A new winner would need to capture the hearts and minds of investors in the way no financial product has done before. The only alternative to making the product ‘sexy’ is ‘fear’, but how would that gain traction? As David Blanchett, Morningstar Head of Retirement Research, said:

"We all know most people aren't on track for retirement. I think surveys that talk about poor savings in the US, or the fact that people haven't saved enough for retirement, are relatively worthless. Kind of like saying, 'The sky is blue'". (Yahoo! Finance, 8 February 2015)

Severe disruption is unlikely

The growth of superannuation assets in Australia is assured by the Superannuation Guarantee regime, making it a highly desirable industry to be in. It must attract new competitors. There’s no denying wealth management will change significantly over the next ten years, just like every industry driven by technology. There will be surprises, developments nobody has yet thought of, perhaps from a couple of young computer geeks in the proverbial garage. Some will do well and drag in a few billion. But that’s not disruption like the executives of Kodak, Blockbuster, Nokia and Borders experienced.

Based on the short and glorious histories of Amazon, Google and Apple and their impact on established businesses, how can anyone conclude that wealth management will not face a similar massive overhaul from a new competitor? Yet that’s my conclusion: I don’t see how any company can make wealth management sufficiently exciting for enough people to grow a market share of 5 to 10% in the next few years. To use Google’s test, what problem will the disruptor solve in such a novel way that hundreds of billions will divert from incumbents? I hope I’m wrong because it would be fun to watch.

Graham Hand has worked in banking and wealth management for 35 years and is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks.