Despite the impassioned discourse across Australia’s major mastheads, realistically Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers had no choice regarding the stage 3 tax cuts. Clearly, the current state of the economy is far different from that in 2019 when the Coalition tabled the tax cuts, which provided impetus for the modifications to be made. Given where we are at in the political cycle coupled with sustained cost-of-living pressures, Labor would have found it difficult to stick with the legislated stage 3 tax cuts that would have predominantly rewarded high income earners.

The famous quote attributed to both John Maynard Keynes and Winston Churchill comes to mind:

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

Unsurprisingly, at the National Press Club announcement, Albanese was quoted as saying:

“We are being very upfront with the Australian people that when economic circumstances have changed, it is a responsible thing to do to change our policy”.

Three main questions

Broadly, three questions remain (brief thoughts are only offered on the first two):

- Will the decision to rework the legislated tax cuts hurt Labor politically?

- Will the new tax cuts be inflationary?

- Are the modified tax cuts a good change of policy?

The answer to the first is uncertain but early evidence is that it won’t. While the revamped tax cuts represent a broken promise, they are not removing an established benefit. Rather, all taxpayers receive a tax cut, it’s just that some receive less than they were expecting. It is hard to argue it will significantly damage Labor given Treasury analysis shows 84% of taxpayers will be better off in 2024-25 under the changes corroborated by Grattan analysis that shows 83% will be better off during the decade to 2033-34.

In the end, you win elections for getting things done, not by breaking promises. I am surprised people are surprised a politician has broken a promise (anyone remember John Howard’s “never ever” promise on the GST…?).

The jury is still out on the second question. The reality is that no-one knows for sure as it depends on several factors including how people will spend their tax cuts. But given the cost-of-living crisis and the fact low- and middle-income earners are struggling with higher interest rates, then it is reasonable to expect the cuts to be largely directed towards mortgage payments which will not impact inflation. Further, given the lack of confidence in the economy, it seems unlikely the post-tax income boost will lead to a huge increase in discretionary spending. Indeed, the Commonwealth Bank’s head of Australian economics said that if all the extra tax relief to low- and middle-income earners was spent, it would boost overall consumption by $4 billion which is a rounding error in a $2.6 trillion economy.

An important point: change not reform!

Before answering the third question, an important point needs to be made. Despite the modifications being touted as ‘tax reform’ by some, they are not tax reform but merely another ad hoc change. In contrast, tax reform requires a long-term objective and a series of substantial changes that when implemented, will achieve the long-term objective. Reform is to re-shape in a positive manner (i.e., improvement) and is structural not transitory (tax rates and scales change relatively regularly).

Are the changes good tax policy?

In the lead up to the backflip, the prevailing winds of public opinion were that the legislated cuts were unfair (i.e., they benefit higher income earners), inflationary, and would worsen inequality (especially for women). There is little doubt, as outlined by Treasury, the modifications improve equity (vertical and gender) and efficiency (more people encouraged to work), help reduce the reliance on personal income tax, and give back some of the stealth tax called ‘bracket creep’. Accordingly, they will help many with the cost of living. However, they could have gone much further to increase the equity, efficiency, and simplicity of the Australian personal tax system.

A politically opportune and socially acceptable alternative

My proposal, based on a unique feature of the UK’s tax system coupled with the implementation of one of Ken Henry’s recommendations, offers an alternative that not only improves fairness but provides a raft of other benefits.

The UK has a progressive income tax system similar to Australia’s with increasing marginal tax rates as taxable incomes climb. But a key difference is taxpayers’ ‘Personal Allowance’ of £12,570 (their equivalent to our tax-free threshold of $18,200) reduces by £1 for every £2 that a taxpayer’s income is above £100,000 (roughly $187,000) meaning the allowance is zero once income reaches £125,140 (roughly $234,000).

The thrust of my proposal is to keep the stage 3 tax cuts as originally legislated but reorient them to Australians in more need while simultaneously returning more bracket creep to middle- and high-income earners as intended. The cherry on top is a substantial reduction in tax system complexity.

First, the tax-free threshold should be increased in line with the recommendation of the 2009 Henry Tax Review. The Review’s favoured model was a tax-free threshold of $25,000 (this equates to roughly $35,000 in today’s dollars).

Second, the tax-free threshold is phased out for higher income earners. For instance, it could reduce by 25 cents for every dollar taxable income exceeds $200,000 (where the top marginal tax rate was to kick in from 1 July this year).

Third, the tax brackets in the original Stage 3 cuts are retained (i.e., a marginal tax rate of 19% on taxable income between $25,000 and $45,000; a marginal tax rate of 30% on taxable income between $45,000 and $200,000; and a tax rate of 45% for taxable income exceeding $200,000).

Everyone’s a winner!

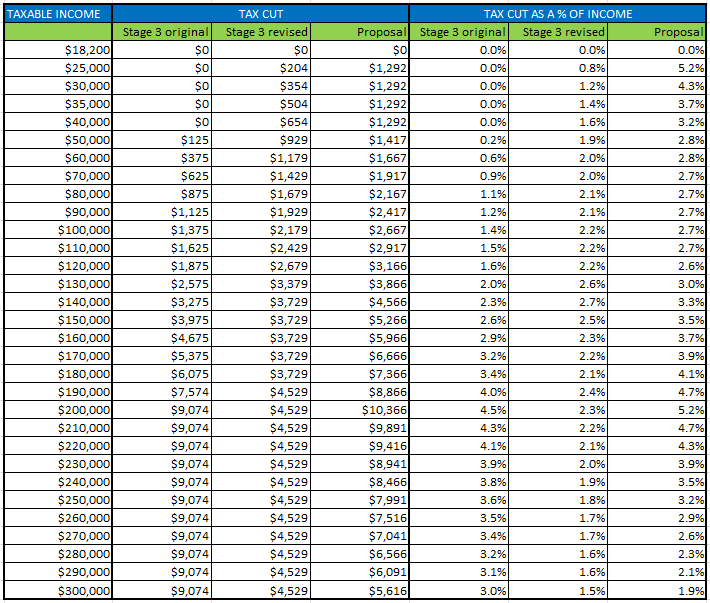

The table below reveals that all taxpayer’s gain under the proposed alternative relative to the current system and the revised stage 3 tax cuts. However, those earning above $230,000 in taxable income (around 350,000 people or 3% of all taxpayers) enjoy less tax cuts compared to the original Stage 3 tax cuts but more than the revised version.

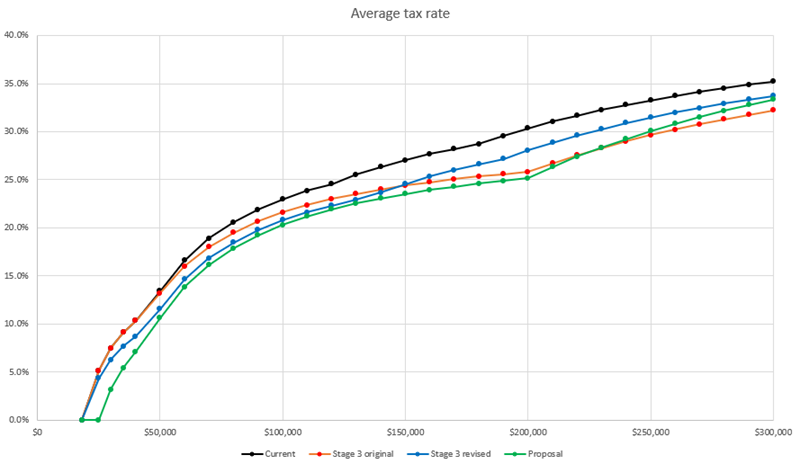

The proposal would lead to a decrease in the average tax rate:

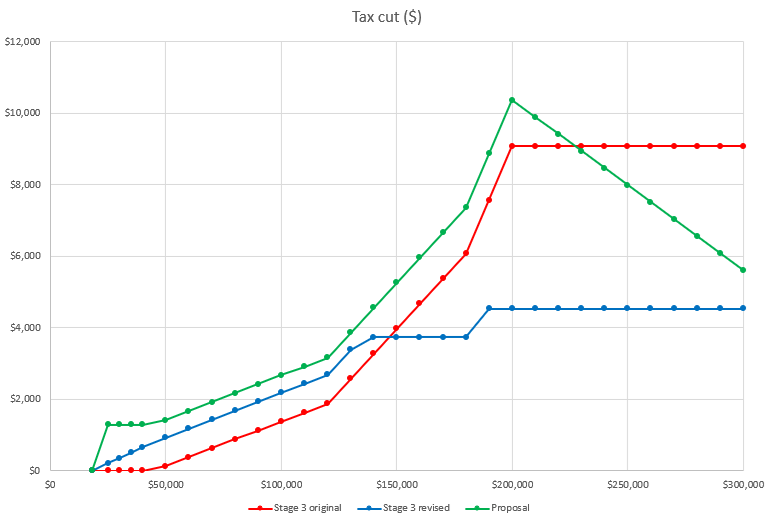

The proposal would put more money into the pockets of all taxpayers relative the revised tax cuts but tapers off at the higher income levels.

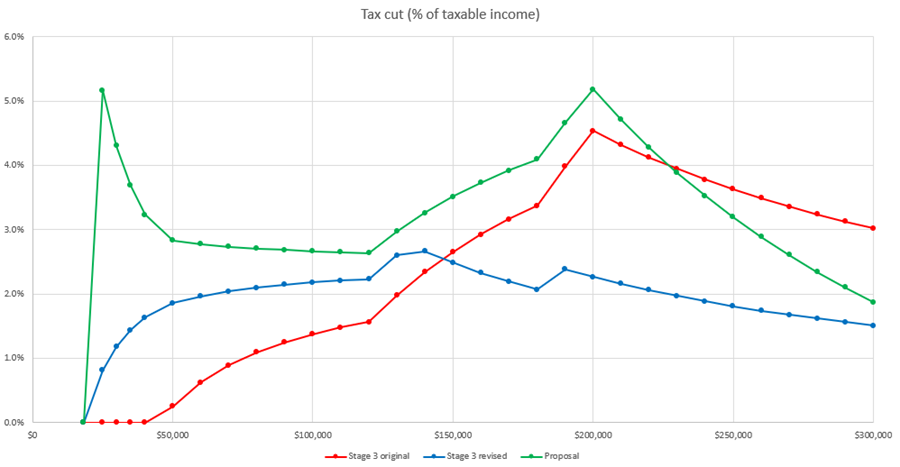

Importantly, as a percentage of income, the proposal would see all income earners gain relative to the revised cuts, but higher income earners enjoy less relative to the original cuts.

Benefits of the proposal

The benefits include:

- It heeds the Henry Review’s call that “a high tax-free threshold with a constant marginal rate for most people should be introduced to provide greater transparency and simplicity”. Streamlined tax brackets are simple and offer incentives to work.

- Removes approximately 350,000 taxpayers from the tax system (based on the latest ATO statistics for the 2020-21 income year). This group represents 3% of all taxpayers and accounts for 0.8% of total taxable income but only 0.1% of total net tax paid. These taxpayers would no longer need to pay any income tax, and many would not have to lodge a tax return greatly simplifying the personal tax system. Interestingly, if the tax-free threshold were increased to $35,000, 1.6-1.7 million taxpayers (14% of all taxpayers) would be removed from the tax system (they account for 4.7% of total taxable income but only 0.9% of total net tax paid).

- Lower tax system costs – lower administration costs for the ATO (resources could be directed elsewhere) and lower compliance costs for taxpayers.

- Reduces Australia’s over-reliance on incentive blunting income tax (as advocated by the OECD and IMF).

- Increased after-tax income for low-income earners struggling with cost-of-living pressures. This group is predominantly female, so this also helps restore gender equity (around 55% of the group no longer required to pay tax are female).

- Aligns the marginal tax of most taxpayers (around 69%) to the main corporate tax rate of 30% thereby minimising incentives to incorporate to reduce tax.

- Ensures high income earners still receive some benefit to compensate for bracket creep.

- Provides a greater incentive for people to engage in paid work thereby strengthening the bond between below-average income earners and the labour market. This should encourage more women into the workforce and may help with skill shortages.

Costs of the proposal

Potential drawbacks include the possibility the tax cuts are inflationary and a negative impact to the federal budget. However, the Treasury analysis reveals that while the redesign of stage 3 is broadly revenue neutral in the short term (reduces tax receipts by $1.3 billion over the forward estimates period from 2023–24 to 2027–28), it will increase tax receipts by around $28 billion over the medium term from 2023–24 to 2034–35. This is the ‘black hole’ Peter Dutton refers to. Why not give more back to taxpayers now?

Of course, additional budget cost may lead to other piecemeal tax ‘changes’ to raise revenue. Rightly or wrongly, Labor was badly burnt at the 2019 election on the back of a platform that included proposed restrictions on franking credits and negative gearing and halving the capital gains discount from 50% to 25%. Despite the potential revenue on the table (the latest Tax Expenditures and Insights Statement released by Treasury last week reveals that for 2023-24, the revenue forgone is $27.1 billion for rental deductions, $56.61 billion for superannuation concessions and $19.05 billion for the CGT discount for individuals and trusts), the 2019 experience will still be fresh in Labor memories meaning Albanese and Chalmers are unlikely to go down this path unless it is part of a comprehensive tax reform package.

Speaking of which, the primary downside of my proposal (or any other offered in isolation) is that it does not form part of a broader reform package with comprehensive changes. It should, and most business leaders and tax experts are now sensibly advocating for such an approach.

So, where to from here?

The proposal outlined here could be tweaked in a myriad of ways, but its essence remains unchanged. That is, all taxpayers are more fairly compensated for bracket creep (this is a continual process since tax brackets are not indexed for inflation) and more support is provided to low- and middle-income earners to help with the cost-of-living crisis.

It should be an interesting week or two in Parliament. Nonetheless, it is frustrating that both parties continue to tinker with the tax system in an ad hoc manner and argue over piecemeal changes while trying to score political points. In doing so, they are letting politics trump policy and continuing to delay the comprehensive tax reform Australia so desperately needs.

Dr Rodney Brown is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Accounting, Auditing & Taxation at UNSW Business School. This article is for general information only, as it does not consider the circumstances of any individual.