Banking regulators have a real dilemma: there is a choice between safety versus effectiveness. APRA could make the system completely safe for depositors, with 25% equity levels and dividends only payable when profits reach a certain level. However, if they did that, they wouldn’t have a banking sector to regulate as the cost of banking products would be prohibitive and/or no investor would give banks capital because there would be no prospect of decent returns. Banking type activities would migrate to the non-bank sector with all the potential issues that come from non-regulated finance sectors blowing up. If they went to the other extreme and let banks operate with very little capital and limited regulation, you get lots of profitable banks and regular banking crisis (see GFC experience).

A banking regulator must try and walk that tightrope. They tend to safety because there is enough evidence that a systemic banking crisis results in GDP falls of 25%. But a risk-free banking system has the same economic result: bad stuff just happens in a different way.

This is where we think APRA is with their call for comment in September regarding AT1. It is a largely subjective trade off, so we think it’s worth discussing.

No loss for existing hybrid holders

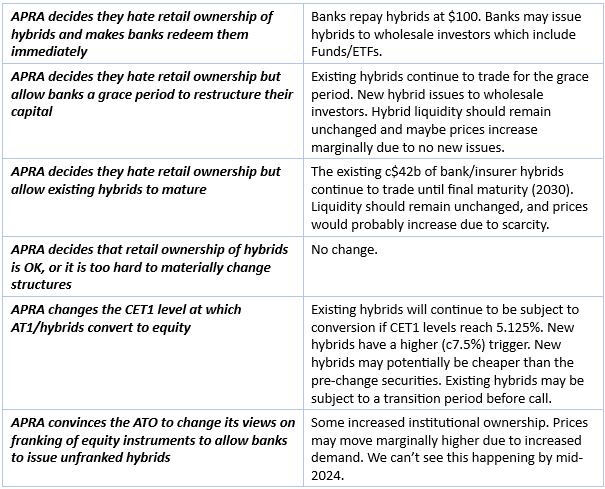

APRA’s call for comment has finished on November 15, and they will release the results in early/mid 2024. Whatever their decision, there should be no loss for existing hybrids. The table below shows a summary of potential APRA decisions and our view of what it might mean for existing hybrids.

Why does APRA object to hybrids?

Both APRA and ASIC have been wary of retail investor exposure to hybrids for the last decade. We don’t think many of the arguments stand up to evidence or discussion, but because they get repeated so often, some of them have gained the status of semi truth. There seems to be a range of arguments from both the discussion paper and the AFR articles in the week after.

This year was about liquidity crisis not solvency events

- (from APRA) AT1 was only used when recent international banks (SVB? Credit Suisse?) had collapsed rather than providing capital support earlier in the crisis.

We disagree with APRA’s interpretation of these events.

SVB was clearly a liquidity event rather than a solvency event. It went broke in the space of less than a month after concerns become apparent. The final liquidity run was just 2 days. Converting an AT1 in that month would not have changed the click induced bank run. Arguably, one of the catalysts for the liquidity event was the recognition that SVB had enormous unrealised losses on securities (due to higher interest rates). If SVB was subject to Basel 3 regulation (or Australian Basel 3 regulation), those unrealised losses would have been deducted from equity levels, and SVB would have been in breach of its capital levels. It would have been required to convert hybrids to equity or raise new equity. If that was the case AT1 would have done its job, but we will never know.

Credit Suisse. For the past 10 years Credit Suisse has been a really bad, but still solvent bank. It was solvent in February 2023, one month before collapse. Its average RoE for the last decade is around 3% and there were continual stupid events. Despite that, it has been operating with 13% CET1 levels over that period, which is above Australian bank levels. Prior to February 2023, it had been able to raise debt and AT1 and Tier 2 capital relatively easily and it had an investment grade rating. This all changed in February/March when deposits disappeared, and the Swiss authorities acted. Bagehot, who wrote the bible on central banking believed “to avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely (without limit) to solvent firms against good collateral and at high rates”. The Swiss forgot that (or never learned), and they shot-gunned a marriage to UBS which involved the wiping out of CS AT1’s. As it turns out UBS paid not much for $57B USD of net assets and the only legitimate post acquisition write offs were about $2.3B of asset/goodwill write downs and $4.5B of regulatory costs. The assets were OK. This was a solvent (bad) bank finished off by a liquidity run. Converting AT1 in 2022 or earlier would not have altered the situation.

Too much retail involvement?

- (from APRA) Australia is an international outlier due to the level of AT1 held by retail investors

And? Australia is also an international outlier in the extent to which retail owns the ordinary equity of its financial system. Direct retail and SMSF probably own more than 40% of bank equity. The major banks have a capitalisation of $400 billion. Hybrids have a market capitalisation of $42 billion. If APRA is worried about the effect of retail ownership of bank capital instruments, bank equity will fall further and faster than hybrids and should create more problems of that kind. It’s hard for us to comprehend APRAs view that it is worried about ‘unsophisticated’ or ‘unaware’ investors investing in hybrids. Since 2021, only ‘wholesale’ investors can purchase hybrids at new issues. These investors almost all use financial advisers, who themselves are licenced and are required to select appropriate investments. Most financial advisers have approved product lists and probably have access to expert/independent advice. We can’t see where the concept of this “knowledge vacuum” comes from.

Clearly, non-wholesale/non-advised investors can buy hybrids on the secondary market. If we look at the 3 largest non-advice broking platforms (Commsec, CMC, Open Markets), they account for around 10% of turnover of all hybrids. All the other turnover is via brokers that offer advice. We think that given the warnings about hybrids, the experience of hybrids going to $0 (Axess, Virgin, Allco, Babcock and Brown etc), and the small number of investors who haven’t received advice, the problems of retail unadvised ownership are not material. We’re not sure that wholesale changes to protect 10% of a $42 billion segment is an example of good policy.

- (from APRA/Media) Problems of banks having to compensate retail investors who own hybrids

In their paper APRA cites examples of Spain and Italy where banks that defaulted/reconstructed had to compensate investors. In at least some of these cases, the banks had offered hybrid type securities to customers alongside deposits. Customers walked into the bank and were offered a deposit or a higher yielding hybrid, without the risks being explained. Unsurprisingly, some opted for the hybrid. When the bank was restructured the hybrid holders suffered losses. The banks had to compensate the investors due to the banks explicit or implicit mis-selling. It’s a little disingenuous for APRA to cite these events as a comparison to Australia. Here banks have no role in investors buying hybrids. There have been no shareholder offers since 2021 and any investment in hybrids is via a financial adviser or via a broking platform. It is difficult to see how the banks would be required to compensate investors as they did in Spain and Italy. The banks’ and APRA’s response would be “go and sue your advisor“. There were also concerns about litigation from upset investors and some speculation that it would be worse from retail investors. It’s not obvious these concerns are valid. Apparently, there were 1000 lawsuits regarding the bail in/reconstruction of the Spanish Bank Popular which was shuttered in 2017. None have succeeded.

Banks won’t stop dividends

- (from APRA) Banks are reluctant to stop AT1 distributions and hybrids haven’t been converted early enough

APRA notes that Credit Suisse didn’t cancel AT1 payments despite incurring losses and facing “uncertain profitability outlook” (we’re not sure when any profitability outlook is “certain”). Let’s start with the observation that hybrid distributions must be paid if the bank pays dividends on the ordinary shares (fair enough). Let’s also note that Australian banks have consistently been viable enough to pay dividends (Westpac has paid an annual dividend since 1817). As per APS 111, banks can pay dividends provided they have an adequate process around capital and are above the required capital buffers. There is a specific waterfall about how much capital they can distribute depending on their equity levels. APRA’s issues about banks paying AT1 distributions are entirely their own making. If APRA is sufficiently concerned about banks making hybrid capital distributions, they can simply instruct banks to stop them. Dividend payment or not does not relate to the structure of AT1 instruments or their ownership. But this is not a consequence free exercise. ANZ lost a lot of money in 1992 (but still paid a dividend). Should APRA have kvetched about banking system capital and exercised its discretion to halt dividends (and hybrid distributions)? As it turns out the directors were right to continue paying dividends. Two years later the RoE hit 18%. If APRA exercised its discretion (and was wrong), investors would have added an APRA risk premium to capital which would have resulted in more costly and less access to capital.

Trigger levels increasing

Under current regulations, hybrids are automatically converted to equity if CET1 levels reach 5.125%. We think that APRA’s view that this is too low for “going concern” capital is valid. If a bank reaches 5.125%, it is a “gone concern”. APRA’s last stress test had the usual dire scenarios (10% unemployment, house prices falling 33%, no equity raisings), but apparently no bank breached the 5.125% trigger level. If those stress test conditions did occur, banks should be raising equity or converting hybrids. If (when!) APRA makes that change, new hybrids will be issued with a c7% conversion trigger. Existing hybrids will retain the 5.125% trigger. We think that pricing of new hybrids will be relatively unaffected in those circumstances. Under current documentation, investors receive $100 worth of shares provided that the share price at the time of conversion is greater than 20% of the issue price VWAP. We find it hard to see bank share prices falling by 80% for a bank which has a mild capital shortage and is reasonably profitable. It’s a different story for equity, which gets diluted pretty heavily if this happens.

Why APRA shouldn’t make wholesale changes

We noted before that regulatory policy is a trade-off between safety and effectiveness. By any standards, APRA is one of the most conservative regulators in the world. The US regulator is reluctant to implement standard Basel 3 because it is anti-economic. Australia’s version of Basel 3 is even more restrictive. Is APRA too conservative? If you ask a new business owner who can’t get bank finance and has to use non-banks or a credit card, APRA probably is too conservative. More concretely, locking retail out of providing bank capital will lead to higher cost of capital and less access to capital.

What eventually happens?

Our inkling is that there will be little change, due partly to the enormous changes that are needed to create a viable institutional market. We can’t see any banks being able to issue to institutions until the ATO allows banks to issue unfranked bank capital instruments. Unless APRA is able to convince the ATO to change its long-held rules on franking of equity instruments within the next few months, their early/mid 2024 response will have to be no material changes to the status quo. In addition, there has been a lack of precautionary bank hybrid issuance in the 2 months since the paper was published.

Conflict of interest statement: we manage hybrid funds. Changes to market structure will affect us but if retail is locked out of direct ownership of hybrids, an unknown portion of investments will transfer to managed funds such as EHF1. Arguably we would end up managing more funds.

Campbell Dawson is Managing Director of Elstree Investment Management, a boutique fixed income fund manager. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual investor. Financial advice should be sought before acting on any opinion in this article. Elstree's listed hybrid fund trades under ticker EHF1.