It is likely that many of us have either encountered or heard of someone who has been scammed. It could be a family member or a friend, and whilst the scams do take a multitude of forms, the highest payouts would seem to occur when a trusted financial institution is impersonated. The trusted relationship – institution to client – gives a scammer an unfair advantage when they infiltrate a banking relationship. The engagement often occurs when a financial institution’s phone number is ‘spoofed’.

It is known (but not well reported) that organised crime groups are running increasingly sophisticated scams by imitating trusted institutions. Importantly, these scams have been easy to arrange. All Australians should be concerned that there are many loopholes that have been used by criminals to undertake these scams. Importantly, recent revelations concerning short term visa ‘money mules’ is disturbing.

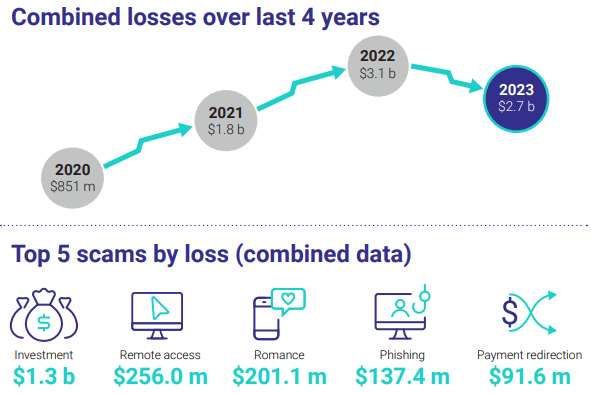

Based on data from Scamwatch, ReportCyber, the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange, IDCARE, and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the combined losses reported in 2023 were $2.74 billion (a 13% decrease in losses on 2022). However, in 2023, Australians made over 601,000 scam reports compared to the 507,000 in 2022 (an 18.5% increase in reports).

Source: Report of the National Anti-Scam Centre on scams activity 2023

From a livelihood and welfare perspective, a scammer can create havoc for an unwitting target. Whether the target loses their life savings, their superannuation, or a deposit for a house, the devastation is the same. Money that is scammed is stolen and lost. It can change lives unless there is recompense.

Whilst my background in investment is extensive, in banking it is both limited and historical. My first job was at the ‘new’ Westpac Bank in the early 1980s as a graduate trainee working in Kings Cross branch where Abe Saffron and other underworld characters were customers. Back then, the Bank of NSW was merging with the Commercial Bank of Australia to create the Western Pacific Bank (Westpac).

In this bygone era, physical deposits (cheques and cash) limited the ability to directly transfer cleared funds without extensive paperwork and phone calls. Fraud was possible but difficult to achieve. Indeed, it was easier to rob a bank than to defraud a bank customer.

But today, that is not the case. Rather than holding up a bank, the scammers (bank robbers by another name) rob the banks’ customers. Further, until a recent judgement by the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA), the banks claimed that the scammed bank customer should bear the loss.

AFCA’s judgement was made in case 12-00-1016692 which was handed down and published on its determination's website on 22 August. There was no press release for this incredibly significant judgement that was made against the HSBC Bank. To quote the basic facts from the case:

“This complaint is about an unauthorised transaction for $47,178.54 (disputed transaction) from the account and who should be responsible for it.

On 13 June 2023, the complainant received an SMS purporting to be from the bank that:

- appeared in a thread of legitimate text messages previously sent by the bank

- referred to a transaction for $740 that was being attempted by Amazon (Amazon transaction)

- contained a 1300 phone number for the complainant to contact if he did not recognise the Amazon transaction.

The complainant had not made, or attempted to make, the Amazon transaction so he called the 1300 phone number in the SMS. The complainant spoke to a third party, who later was found out to be a scammer. The scammer caused the complainant to disclose two six-digit passcodes, which ultimately enabled the scammer to make the disputed transaction.”

The panel decided that the bank involved should reimburse the customer back for the amount they were scammed. The panel stated:

“liability must be decided in accordance with the ePayments Code (Code). Under the Code, the complainant will be liable for the disputed transaction if he voluntarily disclosed the passcodes to the scammer.”

The panel made a significant point:

“The panel is satisfied the scammer’s manipulative tactics resulted in a degree of coercion that impacted the complainant’s free will and choice, so the complainant felt compelled to disclose the passcodes. In forming its view, the panel has taken matters of fairness and reasonableness into account. The panel is satisfied the scammer created a sense the complainant needed to act urgently to prevent the loss of his funds, and the overall impression he was dealing with the bank, and it would therefore not be fair in all the circumstances to find the disclosure of the passcodes was voluntary.”

This decision, in favour of a customer, appears to be the first made by AFCA and despite years of denial by banks of any liability suffered by scammed customers. One wonders whether historical claims that have been rejected by banks may now be revisited.

Notably, Australia’s legal protection for bank customers is a fair way behind a recent law change in the UK. From 7 October, UK banks will have to mandatorily refund bank customers who have been tricked into sending money to scammers up to 85,000 pounds (capped), in just five days. Importantly, after the refund, the paying bank could claim 50% of the payout from the bank the fraudster used to receive the money.

Australia’s proposed new laws don’t follow the UK precedent

Australia’s proposed new scamming protection laws are summarised as follows:

- The claimant can seek reimbursement by making one complaint that includes several parties accused of failing to stop the scam.

- The claim could include banks, digital platform providers, direct messaging service providers, search engines and telcos; and

- AFCA (the Ombudsman) will then work out how much (what percentage) each company is responsible for reimbursing.

Notably, but not unexpectantly, Australian banks argued against the adoption of the UK scheme in Australia. Also notable is that UK bank customers are already protected by confirmation of payee technology which Australia will belatedly fully adopt in 2025. With instantaneous cash value transfers between inter bank accounts, this protection is urgently needed.

“International Students as Money Mules” AUSTRAC and AFP – released June 2024

A recent report by Austrac also has received little publicity yet it openly outlined as to how simple it was for international crime syndicates to infiltrate the Australian banking system and therefore scam its customers.

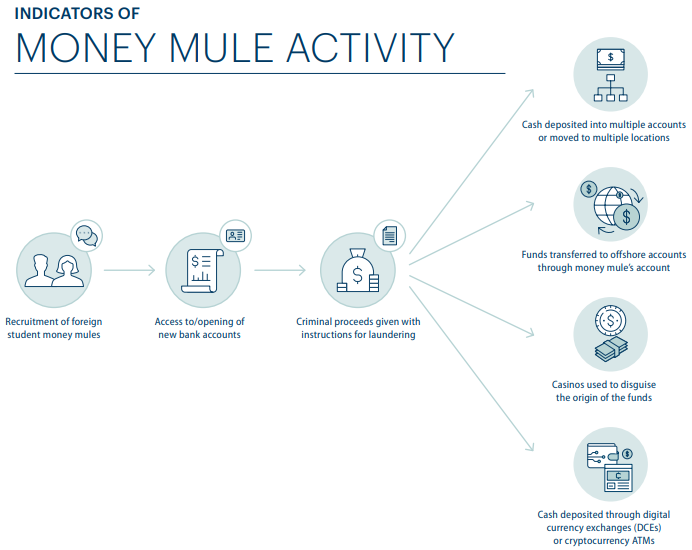

It outlined that criminal networks launder illicit funds through the use of ‘money mules’, which creates distance between the networks and the crime, and helps to avoid detection by law enforcement. They often target international students and non-permanent residents, offering them a way to make money while living in Australia.

At times, mules may voluntarily aid criminal networks. For instance, they may respond to advertisements looking to purchase personal bank account details once they are no longer needed and sell their accounts to criminal groups for mule activity. However, some money mules are unaware that their actions are illegal, often believing their facilitation of funds transfers relates to legitimate employment.

The AFP, AUSTRAC and ABF have identified international students and non-permanent residents in Australia as high-risk groups who are vulnerable to being recruited as money mules.

- International students currently studying in Australia can be recruited as money mules in order to earn money while studying.

- Other money mules are sent to Australia by criminal networks and exploit student visas as a means of entering the country to conduct money mule activity, with no genuine intention of studying.

Criminal networks use a variety of means to recruit foreign student money mules through face-to-face contact or online platforms. They target both legitimate and illegitimate student visa holders and can recruit others outside of the student cohort.

Criminal networks are targeting visa holders who may be paid to buy existing account and identification details that are no longer needed by the departing individual. These accounts and identification details are then used to open additional bank accounts. Criminal networks then create new banking customer profiles and accounts across multiple financial institutions to launder illicit funds.

These accounts are critical in the placement and layering stages of the money laundering cycle and enable:

- circumventing daily banking limits of individual accounts

- increased volume of funds to be moved

- increased number of bank accounts controlled by the criminal network

- reduced know your customer (KYC) requirements for profiles that are already established.

The report produced the following chart that covered ‘Money Mule’ activity:

Source: Austrac.gov.au

Why the secrecy – Austrac/AFP and AFCA?

I question the reasoning behind the apparent suppressing of these significant rulings (by AFCA) and scamming reports (by Austrac)? To whose benefit is it to understate the valuable background information on scamming and the regulatory decisions that may protect bank customers?

Both are significant. Australians should be made aware that international crime networks are accessing bank accounts that have been effectively transferred to their control by short-term visa holders to Australia. The simplicity of the arrangements is staggering and exhibit a lack of diligence by both our banks and regulators. Surely, Australia’s banking regulations should critically control the extent to which non-citizens can utilise and access bank accounts.

It is also significant to the thousands who have been scammed and have or are seeking compensation from their bank, that AFCA has ruled and determined in favour of an aggrieved customer and against a licensed bank. The granting of full compensation for loss, when a customer was scammed through intimidation into disclosing sensitive personal banking information, is groundbreaking.

Let's be clear regarding the banking system and the activities of scammers. The ability to circumvent the identity laws for operating a bank account, allows criminals to transfer money from an intimidated customer's bank account to another bank account, and straight out of the country where it can’t be retrieved.

Why do Privacy laws protect criminal activity?

Claimants when chasing recovery of their money, rightfully seek the help of the banks that were used by criminals to receive their funds as part of the scam. However, Banks have aggressively used privacy laws to push back against investigation by claimants. They have claimed that they cannot release bank account information even if a fraud has clearly taken place.

Think about the scamming transaction - for a customer of Bank ‘A’ to be swiftly scammed requires an illegal account (a recipient account) to be held at Bank ‘B’. Once received, the account at Bank ‘B’ is immediately accessed to sweep the money out of the country - in a matter of minutes!

Could it be that the whole banking industry uses the claim of client ‘privacy’ as another way of stalling recompense? Whilst the criminal’s name is not on the account, the person (short-term visa holder) who transferred their account is. They should also be held to account.

Is it possible that Bank ‘A’ does not chase Bank ‘B’ because invariably the same scam will happen in reverse in due course. A sort of “Gentleman's Agreement”?

Therefore, if it is now the case that Bank ‘A’ is held to be liable to its aggrieved customer then they will surely claim against Bank ‘B’. That is why the recent AFCA ruling is so important and anyone whose claim for compensation was rejected by a bank in the past should be encouraged to revisit their claim.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.