The latest Intergenerational Report (IGR) postulates the three pillars of the Australian retirement income system as the age pension, compulsory superannuation and voluntary saving. All three are looking increasingly shaky for the task ahead, as policy struggles to cope with changes, especially in life expectancy. The failure to increase the eligible age for the age pension has been one of many flaws in retirement income policy, caused by changes that accelerated in the 1970s.

Life expectancy at time of pension eligibility

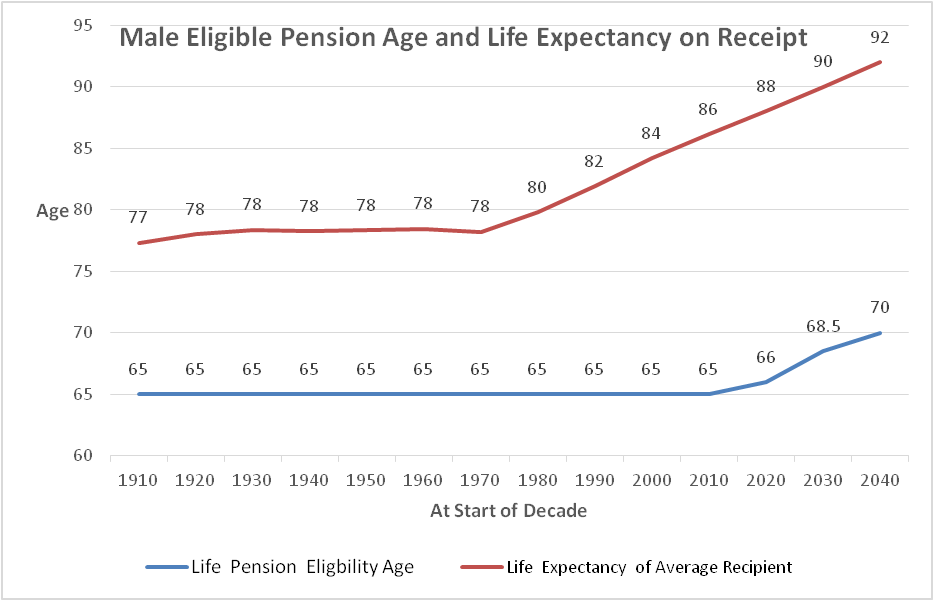

The IGR graphs life expectancy against pension age eligibility (page 70). Unfortunately it uses the life expectancy of a baby. A better insight comes from using the life expectancy at the age of eligibility for the age pension, which for males has stood at 65 for more than 100 years. It is belatedly being increased from 2017 so that by 2035 it will have reached 70 for both genders.

The increase in eligibility is too little too late. From the inception of the age pension, male life expectancy at age 65 rose only slowly until the 1970s (ABS numbers rounded to the nearest year). From then it increased by roughly two years per decade until today and this is expected to continue, as shown.

The last two federal governments have initiated increases in the eligible pension age which top out at 70 in 2035. The chart shows that the gap between eligibility age and average life expectancy for males is likely to have increased from 12 years in the 1970s to 22 years by the decade starting 2040. For female life expectancy, add about four years at age 65, resulting in an even greater gap.

On the face of it, the chart shows just how badly successive governments have failed to respond to the ongoing increase in longevity. The shift towards an older population has further compounded the problem of funding the age pension.

Lower returns and compromised expectations

In earlier Cuffelinks articles (such as this), David Bell neatly defined the many issues in attempting to reform an age pension system that has for so long failed to adapt to the reality of ongoing longevity increases.

Failure to adapt the superannuation system to increasing longevity is likewise building in a gap between expectation and reality. Lower economic growth and low interest rates (in real terms, negative returns in many countries) feed through to entrenched lower returns, leading to a widening gap between perceived need and funds availability. Policy should determine whether the age of access needs to be increased as well as contribution levels.

Financial adequacy is only part of the problem. Financial literacy programs are improving as well as financial awareness at the individual level. People should increasingly be able to conduct an effective financial conversation and contribute to decisions about their savings.

Longevity awareness crucial for retirement planning

The foundations of retirement planning need to be deeper. Few people are aware of their personal time frame that the three pillars need to support. Failure to increase the age of access to the age pension and superannuation has fostered an expectation that it is reasonable to expect access at much younger age than is realistic, other than for those in genuine need. This also has an impact on willingness to add to voluntary savings, the important third pillar.

There is an urgent need to improve longevity awareness across the community, especially at times of tight budget funding.

Since people become more different as they age, using averages such as from the Life Tables is unhelpful. Averages are misleading for individuals and actions that people can undertake need to be personally framed, not generic.

Once people start to recognise what influences their personal longevity, they can take personal ownership of the financial consequences. As a first step, they can begin to address any unrealistic expectations of maintaining living standards with increasing age in the absence of better personal planning such as increasing savings and working longer.

Longevity awareness can underpin weaknesses in the increasingly shaky three pillars. Collective action to boost longevity awareness by governments needs to be complemented by individuals who are well enough informed to commit to making the best of their opportunities to secure their future.

David Williams began longevity research in 1986 and was a Director with RetireInvest and CEO of Bridges. He chaired the Standards Australia Committee on Personal Financial Planning. David founded My Longevity Pty Limited in 2008.