Market commentators and investors regularly use the wrong metric and distort the investment dialogue on yield and income. Let me start this by reminding everyone of my preferred definition of investing: ‘the use of money to produce a regular income'. Contrast this with the definition of speculation: ‘buying and selling in an attempt to benefit from a fluctuation in the price’.

In general, the profit of a company is split broadly in two:

- retained earnings for R&D, new technology etc and

- the balance, or payout ratio, as a dividend.

In mature, quality companies, earnings drive dividends and it is dividend growth, reflecting growing earnings, that ultimately drives share price performance.

In an article in The Sydney Morning Herald by Elizabeth Knight, she writes on CSL:

“This is an old-fashioned growth stock - one that lifts profit every year - and ploughs much of it back into research and development and boosts its capital expenditure. It traditionally spends about 10 per cent of revenue on R&D and is currently working on, among other things, a $US550 million ($810 million) clinical trial to prevent secondary heart attacks. Investors have given CSL the mandate to invest rather than reward them with hefty dividends ... The factor that sets CSL apart from its peers among the largest five Australian companies - BHP, the Commonwealth Bank, Rio Tinto and Westpac - is that investors are not buying into it to chase dividend yield ... based on Wednesday’s share price of $233, the yield is a relatively paltry 1.15 per cent.”

On these quality growth stocks, the yield never looks attractive

As an investor, I never chase current yield. It is income over time I am looking for. Yield is an abstract obtained by dividing two dollar values, the most recent dividend and the current share price. Thus, this abstract is hostage to movements in either one or both of these numbers.

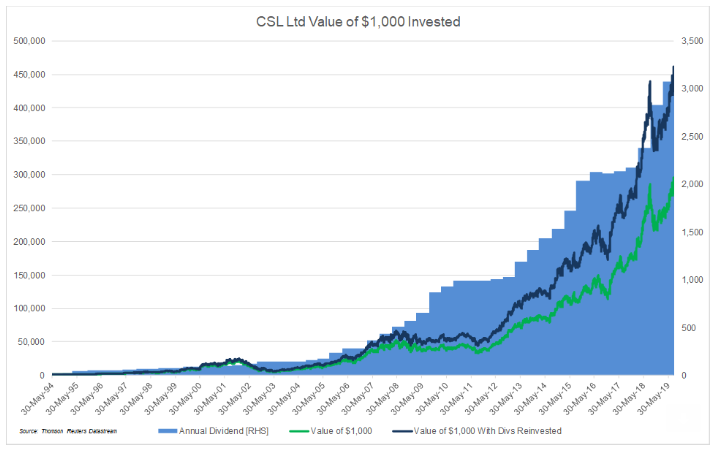

CSL, like a number of other successful companies such as Cochlear and Credit Corp for example, are low yielding for the simple reason that as the profits and dividends grow, the share price goes up. Because of the phenomenal growth in share price (a result of the phenomenal growth in profits) when you divide the dividend into a rising share price, the yield never looks attractive.

Added to this, the success and strong dividends associated with these three companies ensures that the price is at a premium which naturally puts downward pressure on the abstract yield. However, unlike the journalist, you should never assume that the low yield is an indication of low dividends and therefore low income.

The three shares mentioned, despite their low yields, have produced an extraordinary income stream.

Credit Corp (ASX:CCP) is my favourite example. Since 2000 we have invested a total of $137,000. Our CCP shareholding is now worth $1.8 million. It sits on a paltry yield of 2%. Why so low? Because the share price has risen at the same stratospheric rate as the dividend. The good news for us is a current ‘yield’, as I judge it, the last dividend divided by amount invested, is 33%. If that isn’t enough, total dividends paid since 2000 now stand at $290,000, a return of more than 200% (not adjusted for inflation) on our capital in income alone.

The same applies for CSL. The following Chart 1 shows the extraordinary growth in both share price and dividends that CSL has bestowed upon its shareholders since 1994.

Ignore the spot yield quoted by many

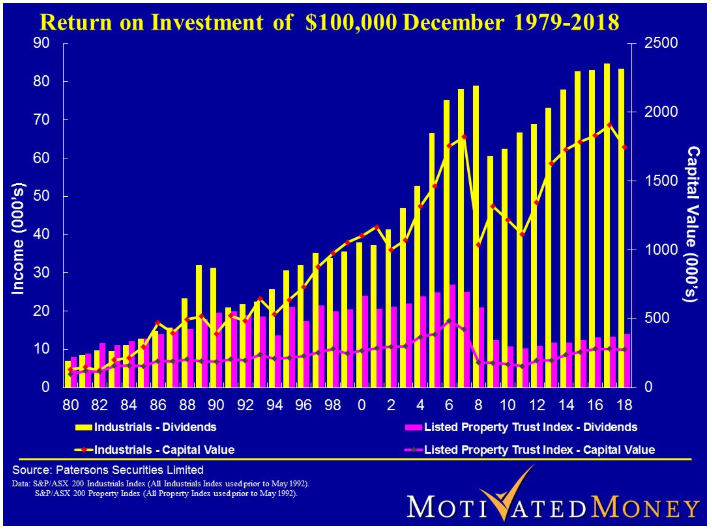

Consider the listed property trust sector, now commonly called A-REITs (Australian Real Estate Investment Trusts). Chart 2 below compares the income from listed property trusts (S&P/ASX200 Property Index) to the dividends from industrial shares (S&P/ASX200 Industrials Index) since 1979. Clearly the shares produce a far superior income over this long term. This is why I have often written about the long-term merits of industrial companies for income versus nearly every other asset class.

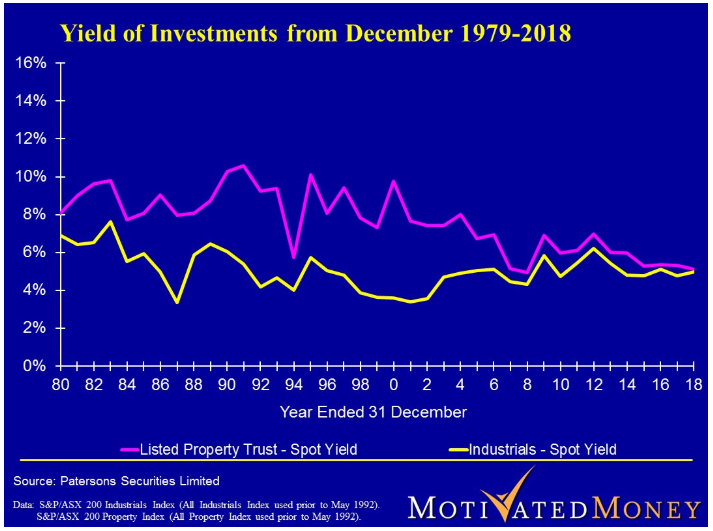

Now consider Chart 3 below plotting the yield of these two sectors over the same period. There can be no doubt that property is a far superior investment for those seeking yield. Ever since I returned to Australia in 1988, I have had people, particularly retirees, telling me that property was a far better income investment than industrial shares because of its superior yield.

The reason the yield on property trusts is high is quite simple. As a result of their structure, they must distribute 100% of their income. Therefore, the vertical income bars (pink in Chart 2 above) represents a 100% payout ratio.

In contrast, the vertical yellow bars represent around 50% of the profits generated by industry. The corporate structure enables companies to retain profits without penalty for research and development, new technology etc.

Think of current yield as an abstract

The trap is baited by the fact that the yield is an abstract numeric (income divided by index value). If dividends remain stable and the share price falls, yields will rise. Conversely, if share prices rise, yields will fall. In Chart 2, the high yield of property is simply a function of the fact that the capital value line is well below the top of the dividend bars. Similarly, the industrials are low yielding because the value line is much closer to the top of the dividend bars.

Now, try and imagine the yield on shares if all companies, like listed property trusts, retained no earnings and paid out 100% of profits every year. If this happened, fewer people would buy property trusts for income rather than industrial shares.

Sadly, time and time again the yield word is used to describe income whilst the reality is that the link between the two is uselessly abstract. Experience has taught me that chasing the highest initial yield will almost certainly result in a worse income over the long term. Oh, and by the way, shares are not growth assets, they are income dynamos.

Peter Thornhill is a financial commentator, author, public speaker and Principal of Motivated Money. This article is general in nature and does not constitute or convey specific or professional advice. Share markets can be volatile in the short term and investors holding a portfolio of shares will need to tolerate short-term losses and focus on a long-term horizon, and consider financial advice.