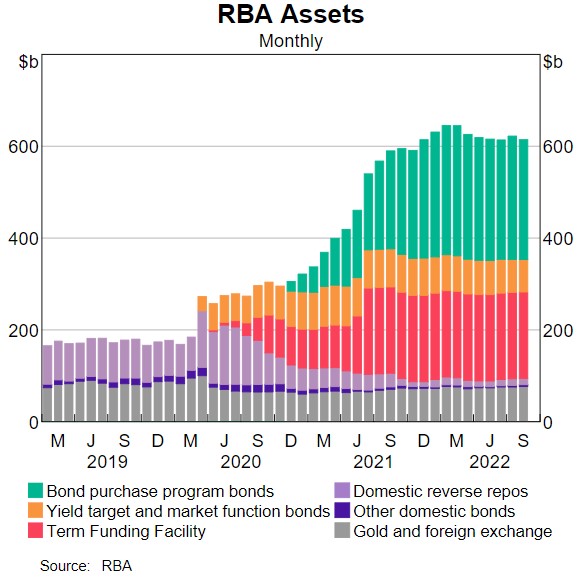

Last week, the Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Michelle Bullock, presented on the central bank's shift from quantitative easing (QE) to quantitative tightening (QT) and its implications. She reported that between November 2020 and February 2022, the RBA purchased $281 billion of federal and state bonds through its QE programme, at a time when the federal government was borrowing hundreds of billions to fund pandemic support measures, including the $90 billion JobKeeper programme. It was the main factor (the green bars below) in a massive increase in the RBA's balance sheet.

The RBA bond purchasing programme was part of the $US11 trillion injected into the global economy by major central banks in response to COVID-19. And with inflation now entrenched in major economies around the world, central banks are scurrying to reduce their balance sheets. The shift is on to global QT.

Faced with rampant inflation, the US Federal Reserve has indicated it is prepared to bring on a recession to control prices. It's ironic that central banks spent trillions to stimulate activity during the pandemic and now they are withdrawing trillions to reduce spending. Central banks are now paying for their largesse.

The RBA announced in May this year that with the QE phase of expanding its balance sheet ending, the QT phase would begin. It would do this by allowing its holdings to run down as they mature, reducing the balance sheet gradually.

QE and QT and the impact on inflation

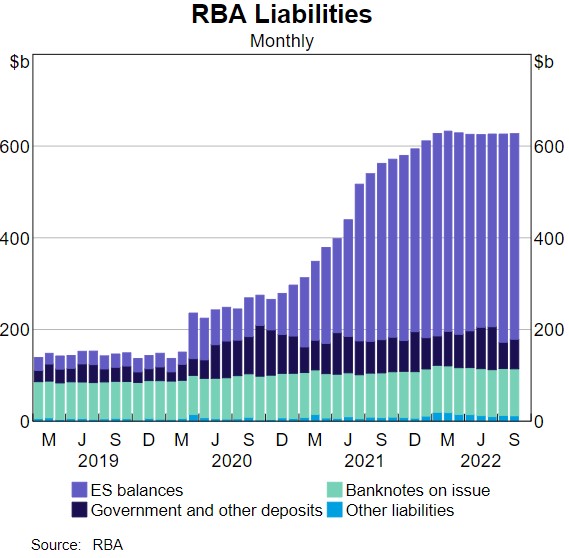

QE involves central banks engaging in large-scale asset purchasing programmes. Government bonds are purchased in the secondary market to lower bond yields and longer-term borrowing costs to provide economic stimulus. Debt purchased is recorded as an asset in the central bank balance sheet, offset by the creation of commercial bank (Exchange Settlement, or ES) reserves recorded as a central bank liability, as this RBA chart shows, the other side of the first chart above.

QE adds to base money in the system, and in doing so runs the risk of igniting inflation if the increase in commercial bank reserves spawns an increase in the broad money supply via lending to the private sector. In suppressing interest rates, it can also inflate asset prices.

Essentially, central banks create base money with QE, in the same way commercial banks create private sector deposits (or broad money) when lending money.

In both instances, entries appear simultaneously on the asset and liability side of their balance sheets, as new money is created.

The RBA’s approach to QT of allowing bonds to mature over time and not reinvest the proceeds is a passive approach. The more aggressive scenario is actively selling its assets back into the secondary market before they mature to reduce its balance sheet more rapidly.

The pace at which QE is unwound, if at all, is of importance. To the extent that QE is not reversed, the actions of the central bank could be perceived to be ‘indirect’ monetary financing. Where monetary financing, as advocated by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), is the funding of government deficits by money creation, instead of issuing debt or increasing taxes. Because when deficit spending coincides with a QE program, that’s what might appear to be occurring.

How Australia financed its spending

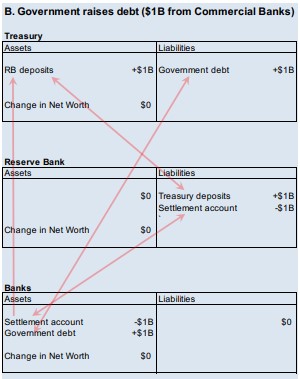

Consider, for example, substantial government spending like the JobKeeper programme. That was financed by issuing debt to the market. At the same time, the RBA purchased debt from the market by creating commercial bank reserves, therefore indirectly financing the Government’s deficit, at least temporarily.

We see here diagrammatically how debt-financed government spending in tandem with a QE program, flows through the relevant balance sheets.

For the purposes of this article, the flow diagram below is one of six in the diagram which shows the flows between balance sheets.

The move from QE to QT

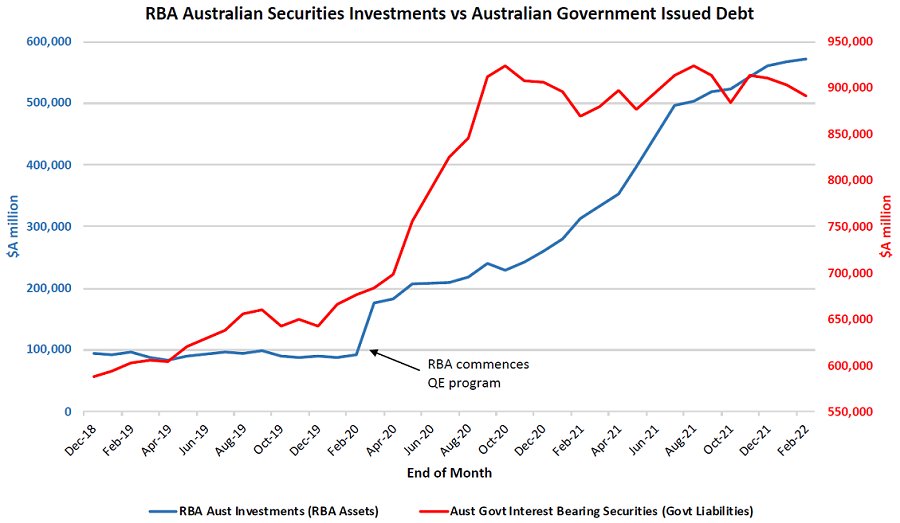

With the RBA balance sheet and government debt rising steeply since early 2020 (see chart below), if at maturity the RBA rolled over that debt, then financing would remain in place. Only when central banks begin to unwind asset purchases and reduce their balance sheets, will monetary financing prove not to be permanent, and be genuine QE.

Now, full QE unwinding may eventually occur around the world, but it may only be partial. With all that has been spent on COVID-19 globally, it is perhaps inevitable that some of that will end up being monetary finance, but central banks will be careful not to make that explicit.

One way to protect a government’s long-term intentions is for the central bank to only trade in the secondary market. That is, with institutions that had already purchased government debt. Indeed, early in its QE programme, the RBA went to great lengths to state that it would not purchase debt directly from the Government (the primary market) to maintain its independence from Treasury.

Minutes of the November 2020 RBA Board Meeting record that:

“the Bank would not purchase bonds directly from the Government, and so the purchase of bonds by the Bank would not constitute government financing.”

And in July 2020, RBA Governor Philip Lowe said:

“I want to make it very clear that monetary financing of fiscal policy is not an option under consideration in Australia.”

Is this 'money printing'?

In reality, however, regardless of whether a central bank purchases debt in the primary or secondary market, a QE programme running parallel to fiscal spending could be viewed as indirect or at least, temporary monetary financing, with the possibility of it becoming permanent.

Optics are often everything though, and with many commentators suspicious of QE, deeming it to be just money printing, free money, and outright brazen, buying in the primary market would not be a good look.

This is why QE only proceeds in the secondary market, downplaying the perception of money printing.

And with the possibility of QE being long term before being unwound, its distinction from monetary financing is often about policy intentions as opposed to how it is implemented.

Independence of the central bank from the Government is important, because without the separation of monetary and fiscal entities, central bankers could fear uncontrolled monetary financing pushed by government, heightening risks such as Weimar Republic-style hyperinflation, that would have devastating economic effects.

Unconventional, experimental - and now comes inflation

These activities by central banks have rightly carried the label of 'unconventional', and they were always an experiment. Prior to the 2007 GFC and COVID-19, unconventional monetary policies such as QE, QT, MTT, and negative interest rates existed more in the realm of the theoretical than the practical. Yet now we have seen much of it implemented with vigour around the world.

The concern with such potent monetary stimulus was always inflation. And now that it has arrived, the challenge for policymakers is to put the inflation genie back in the bottle and decide how mainstream such policies should become going forward while being mindful of supply-side inflation arising from the likes of a pandemic or a war.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

A version of this article was originally published by The Institute of Actuaries of Australia.