Experienced investors do not seek danger, but they may accept uncertainty in exchange for growth potential. Technology companies illustrate the principle. Most fall by the wayside, but the ones that live to dominate their rivals can create large fortunes by adding boatloads of new customers. The more buyers feeding the top line, the fatter the bottom line.

Not every company succeeds through expansion, though. There are other ways for businesses to enrich their shareholders. A prime example is See’s Candies, owned by Berkshire Hathaway BRK. A. Despite increasing its customer base only glacially, it has been a hugely successful investment.

Background

Berkshire Hathaway’s 2007 shareholder letter provides the essential details. In 1972, the company paid $25 million to buy the privately held confectioner. That year, See’s sold 16 million pounds of candy, generating $30 million in revenues and “less than $5 million in pretax earnings.” (Another source is more specific, citing a $4.0 million pretax profit, which I used for my analysis.) Thirty-five years later, its unit volume was 31 million pounds.

At 1.9%, the company’s annualized growth of candy production barely exceeded the rise in US population. Had See’s reinvested each year’s profits back into its business and adjusted both its candy prices and costs to match the prevailing inflation rate, 1.9% would have been its annual real return. All the company’s profit growth would have come from selling more pounds.

Obliging customers

Fortunately for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, See’s raised its prices by more than the inflation rate. Charlie Munger once stated, “Over time we just discovered that we could raise prices by 10% a year and nobody cared.” He exaggerated. If See’s management had tracked inflation for the first decade after its acquisition, then hiked its prices by 10% annually since 1982, a single pound of See’s candy would now cost $274. It does not.

See’s did enough. From 1972 through 2007, it increased its prices by 0.8 percentage point per year above inflation—5.5% for its sweets, as opposed to 4.7% for the Consumer Price Index. That doesn’t seem like much. However, thanks to the twin magics of compounding and operating leverage, that modest annual raise doubled the company’s profit margin. As the firm’s unit sales had also doubled, its real pretax earnings quadrupled.

3 forecasts for See’s Candies

A further consideration before considering the performance of See’s Candies is valuation. Berkshire Hathaway paid 6.25 times pretax earnings for a business that became more profitable than anybody expected. In addition, corporate tax rates declined over that period, thereby boosting the worth of pretax earnings. Consequently, See’s would have commanded a much higher price multiple in 2007 than it did when purchased. I estimate a ratio of 16 times.

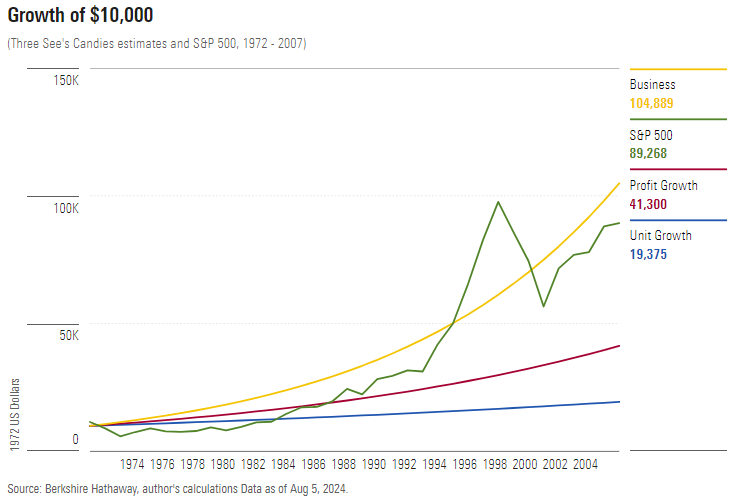

Let’s assemble this information. The chart below compares three projections for the ongoing market value of See’s Candies to the total return of the S&P 500, over the period from 1972 through 2007. The forecasts consist of 1) unit growth, 2) profit growth, and 3) a full corporate assessment, which includes the effect of its higher price/earnings multiple, per my assessment.

My guess is that you’re not terribly impressed. On its operational results alone, See’s Candies could not keep up with the S&P 500. Admittedly, Warren Buffett bought the business at a discount, so if he had sold it he would have been slightly ahead of the pack. However, this analysis does not justify my statement that turtles could run like hares. Above average is not the same as excellent.

But remember the initial assumption that See’s reinvested its profits back into the business? It was almost entirely false. The quiet part of the See’s story—and it’s the very best part—is that its operations required almost no outlays. (Such can be the benefit of sluggish unit growth.) From 1972 through 2007, See’s Candies generated $1.35 billion in pretax profits but spent a mere $32 million on capital improvements.

See’s Candies: with dividends

In Berkshire Hathaway’s case, that excess cash went into the corporation’s coffers. Had See’s been a public company, those moneys would have either been distributed as dividends or squandered. Given how well See’s is managed, let’s assume dividends. We must now therefore include them to make a fair performance comparison, since the S&P 500's total returns (as with all indexes) account for dividends.

And the dividends would have been large indeed! In 1972, after funding its modest capital allocation and paying its far greater tax bill (that year’s corporate tax rate was 48%), See’s would have had $1.95 million available to distribute, making for a 7.8% annual yield. A sweet deal.

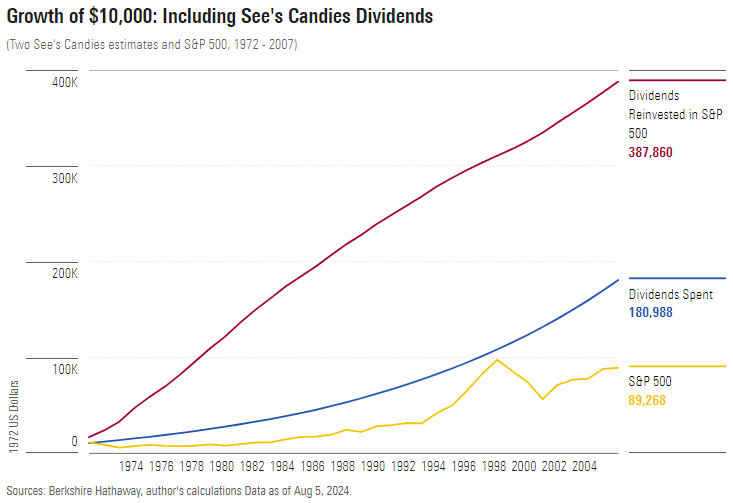

This time, I present two versions for the putative stock market performance of See’s. The relevant comparison is with its dividend payouts redistributed into the stock market—which, as stated above, is how the S&P 500's returns are calculated. (I thought about reinvesting the dividends into See’s itself, but that was one hypothetical step too far.) A more conservative approach is to assume that the dividends generate no further profit because they are immediately spent.

Below are the results for each method. Once again, all results are presented in 1972 dollars.

This time, I can convincingly claim victory. By my accounting, if See’s Candies had been a publicly traded company, an investor who bought its shares in 1972 and held for the next 35 years while reinvesting the company’s copious dividends back into the stock market, would have turned a $10,000 initial investment into more than $387,000 after adjusting for the effect of inflation. That means $1.9 million in nominal terms.

Conclusion

This isn’t ancient history. Since 2007, See’s Candies has boosted its margins more aggressively, by raising its prices by an annualized 5.5%, while inflation has averaged 2.5%. For more than half a century, the company’s essential story has been unchanged. Year by year, See’s earns more from its existing customers while throwing off oodles of excess cash. Those moneys can be invested elsewhere. See’s does not need them.

This article, of course, only offers a hint of the many factors that separate winning from losing investments. Besides top-line growth, pricing policies, and capital requirements, which we discussed today, other major considerations include cost containment, acquisitions, and share dilution. But I hope to have illustrated a broader point: Great stocks need not be growth companies, as the term traditionally is defined.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's Investment Research Department. The opinions expressed here are the author's. The author owns shares in one or more of the companies mentioned in this article. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Originally published by Morningstar and edited slightly to suit an Australian audience.

Try Morningstar Premium for free