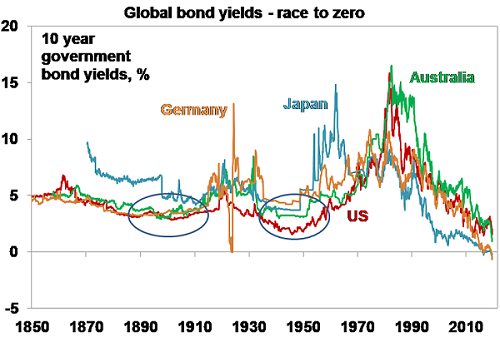

Since the RBA started cutting interest rates again in June 2019, there has been increasing debate that it will deploy so-called 'unconventional monetary policy measures' such as negative interest rates and quantitative easing (QE). This debate has hotted up in recent weeks after the escalation in the US-China trade war posing a rising threat to global growth, numerous central banks cutting interest rates this month in a so-called 'race to zero', the Governor of Reserve Bank of New Zealand saying that negative rates are possible and RBA Governor Lowe saying that its “prepared to do unconventional things if the circumstances warranted it” even though he also said that QE was “unlikely”.

But what exactly are these unconventional monetary policy measures? Do they work? Would they work in Australia? Are there better options? Will they be deployed and when? What will it all mean for investors?

What’s behind talk of unconventional monetary policy?

Put simply Australian economic growth has slowed sharply below its long-term potential reflecting the housing downturn and weak consumer spending. While house prices may be bouncing back in Sydney and Melbourne and there are anecdotes that the tax cuts are helping retailers, the downturn in housing construction has further to go and other factors from drought to the threat from the US trade wars cloud the outlook with increasing talk of recession globally. Slower growth has seen the outlook for unemployment deteriorate – at a time when there is still a high level of unemployed and underemployed (at 13.6% of the workforce). Which in turn threatens to keep wages growth and inflation lower for longer. So, with the cash rate approaching zero the question naturally arises of what to do next? Of course, Australia is not alone. There is an excess of global savings and this is driving ultra-low interest rates.

Source: Global Financial Data, AMP Capital

What are unconventional monetary policy measures?

They refer to a bunch of policies which have been deployed by major central banks in the aftermath of the GFC. They are:

- explicit forward guidance – where the central bank indicates the cash rate is not expected to rise for some time period

- very low and negative policy interest rates

- QE which has involved using printed money to purchase public and private securities

- providing cheap funding to banks to support lending, and

- intervening to push the Australian dollar lower.

But do they work?

A common comment is that “QE etc hasn’t worked in the major economies so why should it work here?”. In reality such policies do appear to have helped notably in the US and Europe where they were progressively deployed from the time of the GFC once interest rates hit zero and then became the lone stimulus measures as fiscal austerity took hold.

Since its high in 2013 unemployment in the Eurozone has fallen from 12% to 7.5% and in the US it fell from 9% in 2011 to 4% in 2017 enabling the Fed to start unwinding unconventional monetary policy. Inflation has not been returned to 2% targets, but wages growth has lifted and at the start of last year it looked like the global economy was getting back to normal. So unconventional measures have helped. Of course, Trump’s trade wars have provided a big threat since then.

The main lessons look to have been that different measures are appropriate depending on the issues facing a country, that a range of measures are preferable to just one and that central banks need to go early unlike Japan which left it too late.

Will it work in Australia?

Our assessment is that unconventional monetary policy measures may help in Australia, but it will depend on the measure deployed and their impact will be limited particularly compared to overseas.

Explicit forward guidance – the RBA has already started this with its comment this month that “it is reasonable to expect that an extended period of low interest rates will be required”. If the US and ECB are any guide this is likely to morph into a specific time period through which rates will remain low. This can help keep bond yields low, but the low yields in other countries dragging our yields down will arguably do this anyway.

Zero or negative interest rates – while the Fed stopped cutting rates in the GFC and its aftermath at 0-0.25% and the Bank of England stopped at 0.25%, the Bank of Japan and several European banks led by the ECB have taken rates negative. This negative rate applied to the deposit rate banks get for leaving deposits at the central bank and was motivated to encourage them to lend out cash which was building up as reserves due to quantitative easing. There is some evidence that negative rates in Europe have boosted bank lending but cut into bank profits because banks are reluctant to take interest rates on bank deposits (which are used to fund lending) below zero and so further falls in lending rates lead to reduced profit margins which may crimp lending. The thought of negative rates may also scare people. Sure a 10% bank deposit rate and 12% inflation is really no different to a -1% deposit rate and 1% inflation – but the former would feel a lot better!

For these reasons it would make sense for the RBA to call a halt to cash rate cuts around 0.5% (which we expect to see by year end) or maybe 0.25%. There would be little point in going to zero or negative as the banks will be unlikely to pass it on in lower mortgage rates as they won’t want to take deposit rates negative. So negative interest rates will hopefully be avoided.

Asset purchases under quantitative easing – QE in the US, Europe and Japan involved pumping printed money into the economy by central banks buying government bonds, high-rated private debt and, in Japan’s case, some shares. This was aimed at pushing long-term bond yields and hence borrowing costs even lower, boosting narrow money in the economy with the hope that it will be lent out, pushing investors into more risky assets to make more capital available for investing and (although they don’t admit it) pushing their currencies down. It tends to be what you do once interest rates have hit zero.

In Australia, QE may provide less help because there are less Government bonds for the RBA to buy given relatively low public debt in Australia, bond yields are already low anyway and in any case 85% of mortgage borrowing is linked to short-term interest rates and so there would be little benefit to the household sector from lower long-term bond yields.

There is no guarantee that the cash pumped into the economy is lent out and spent and a lot of it has just helped share markets (which is good for the better off) at a time when interest rates are low (which is not so good for lower income earners who rely more on bank deposits).

Cheap funding for banks – the RBA did this around the time of the GFC and the ECB and the Bank of England have provided cheap financing to banks tied to them boosting lending. It’s not really an issue at present in Australia as banks are not facing difficulties in terms of funding and the recent slowdown in credit growth in Australia owes more to tighter regulatory oversight around “responsible lending”. However, following the UK experience the provision of cheap funding to banks may be a way for the RBA to ensure that cash rate cuts are continued to be passed on to lower mortgage rates and that lending holds up as the cash rate gets closer to zero.

FX intervention – this is a return to old fashioned RBA intervention in the foreign exchange market to push the $A down by selling Australian dollars and adding to its foreign exchange reserves with the aim of helping growth. It seems unlikely though as it would be criticised by other countries as competitive devaluation and the $A is already low anyway.

Will the RBA deploy unconventional policies?

The RBA is likely to exhaust conventional easing by cutting the cash rate to 0.25-0.5% before doing unconventional measures beyond forward guidance. The probability of other measures next year is rising. Negative interest rates are unlikely but quantitative easing would likely be included. Ideally this would involve working with the Government to provide a fiscal boost.

Implications for investors?

There are a number of implications for investors.

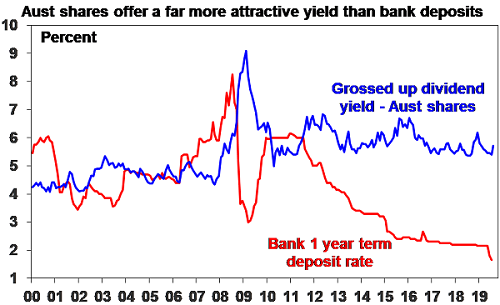

First, bank deposit rates are likely to fall even further and remain unattractive for a lengthy period yet.

Second, the low interest rate environment means the chase for yield is likely to continue supporting commercial property, infrastructure and shares offering sustainable high dividends. The grossed-up yield on shares remains far superior to the yield on bank deposits. Investors need to consider what is most important – getting a decent income flow from their investment or absolute stability in the capital value of that investment.

Source: RBA, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Third, the continuing low interest rate environment will support Australian residential property prices, but still high debt levels, tight lending conditions and rising unemployment mean that it’s unlikely to set off another full-blown property boom.

Finally, easy monetary policy in Australia will likely help keep the $A lower than it otherwise would be.

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP Capital, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Subscribe to AMPC's Insights here.

For more articles and papers from AMP Capital, please click here.