Macroeconomic analysis is extremely useful in explaining both the past and describing the present. Whilst its utility at forecasting the future is subject to debate – in my view it is a pointless one. That is because there can be no doubt that macro events constantly move markets. Simply reflect (if you need a recent example) upon how markets reacted to the announcement of Australia’s June CPI – the share market lifted, bond yields fell and the AUD sank, all within minutes of the data release. Then when there were signs (a few days later) of the US economy slowing with poor industrial output and weak employment data - the equity market slumped, bond yields collapsed and the AUD rallied as the USD devalued on higher probabilities that the Federal Reserve will cut cash rates in September. Macro events caused a liquidity rush towards assets regarded as low risk or defensive.

Whilst macro readings have an immediate effect on daily prices of assets, these prices are driven by sentiment shifts that are magnified in large part by traders and hedge funds. Long-term investors reflect on macro-observations to reconsider their acquisition (accumulation) price of assets or adjust their thoughts for asset allocation. Traders jump in, trying either to front run the trend or to stimulate short-term price movements for their advantage. They seldom have a thoughtful macro approach and are increasingly matching wits with computer-driven trading programs. The result is short-term price volatility that often reflects little of longer-term consequence and are the result of a programmed thought process – human into computer, and reflects noise rather than analysis.

The importance of both macro analysis and macro thought is not necessarily about forecasting the actual economic numbers. Rather, it is about connecting the projected economic outcomes with a considered view about how the new information might influence one’s expectations of returns from the various investment asset classes.

Invariably, the world economy grows each year and global recessions are rare – over the last 40 years there have been just two – the GFC and the Covid pandemic. Therefore, almost invariably, long-term investment returns result from staying invested and from compounding returns.

Economic dogma is everywhere

To undertake macro analysis requires more than a dogmatic approach to economic theory. However, much economic analysis has become overwhelmed with economic group think driven by Central Bank speak. For example, quantitative easing (QE) was widely adopted as the major monetary policy tool that dominated economic management following the GFC – but which Central Bank openly admits to it or explains its precise processes and objectives?

This introduction brings me to discuss the topic featured in my headline – “Do budget deficits create inflation?”

They can and have, but they don’t always. At present in Australia, I would argue that an extremely focused inflation-fighting budget (substantial attacks on both the cost of living and of doing business) would see a budget deficit that would drive down inflation and interest rates. Breaking an inflation cycle can be undertaken by aggressive fiscal policy. Importantly, it would be a fiscal policy (i.e. a deficit) that is highly consistent with fiscal policies around the world.

It does not take too many observations of major economies and their fiscal outcomes to show that fiscal deficits did not create inflation following the GFC. More pointedly, specific observations of Japanese fiscal outcomes (massive fiscal deficits) since 2000 did not lead to runaway inflation.

So why is there a chorus of claims by so many economists, commentators, and politicians that the government needs to reign in its expenditure or run a budget surplus to fight inflation? Why is there a dogmatic belief that a budget deficit will add to inflationary pressures? Why is there little analysis of government deficits to differentiate between those that attack inflation outcomes as opposed to those that add to them?

Before touching on Australia’s fiscal outlook and inflation, let's look at world inflation at present and investigate the history of US and Japanese budgets, their debt blowouts and inflation outcomes.

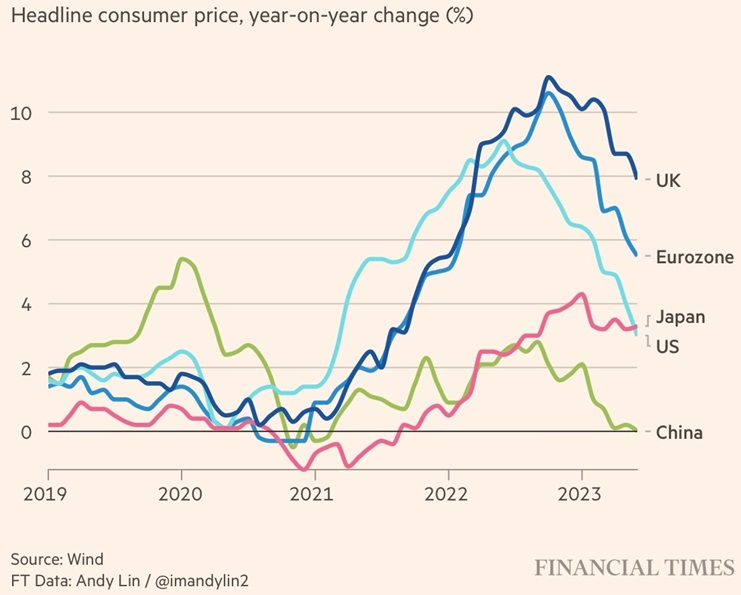

First, inflation across the world’s major economies has peaked. It was clearly stoked by the consequences of Covid and the Ukraine war. Indeed, inflation surged in 2022 to exceptional levels reminiscent of the 1970s when an oil price shock created ‘cost inflation’ across the world.

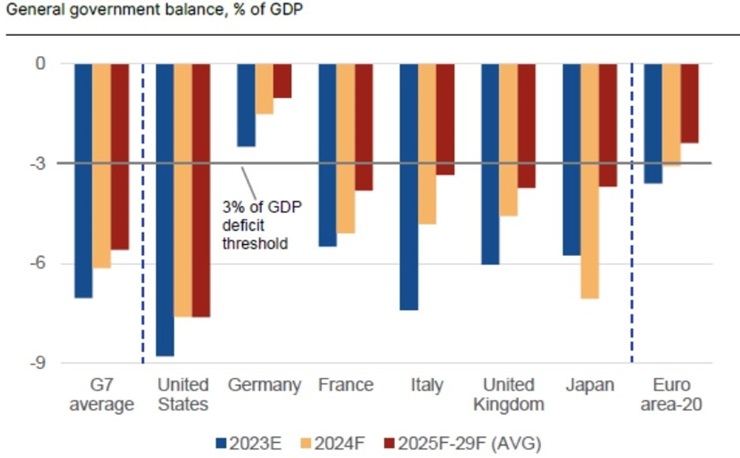

Further, the inflation surge had nothing to do with the budget outcomes or policies of major economies. Whilst all major economies are suffering large fiscal deficits, those deficits were in existence prior to Covid – but just at lower levels compared to GDP.

Source: Bloomberg

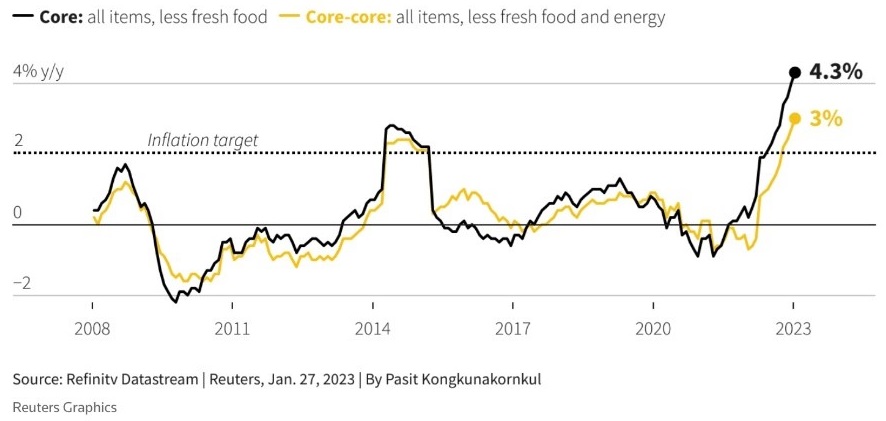

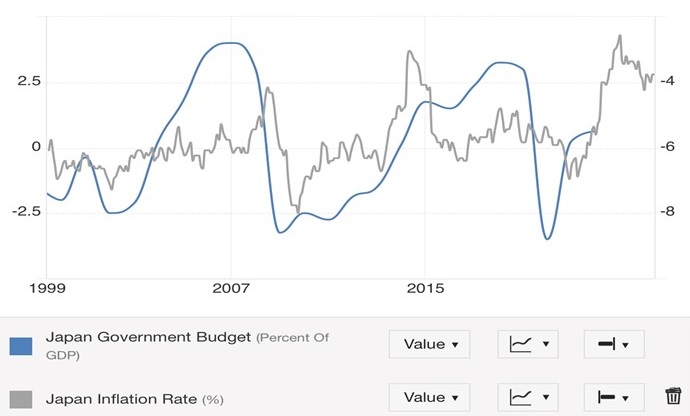

The following chart from Trading Economics compares the Japanese budget outcomes to inflation outcomes over the last 25 years. Fiscal deficits since the GFC have rarely been less than 4% of GDP and surged to 10% in Covid. Meanwhile, inflation readings have hovered around zero, with a mild outbreak in 2015 and a more recent surge following Covid.

There is no discernible correlation between Japan’s large budget deficits and inflation. Indeed, the opposite is true. On reflection, one could argue that the maintenance of extremely low interest rates (sometimes negative) added to dis-inflation in Japan. There is too little reflection by economists on the role of the cost of money (credit) on the cost of living or the cost of doing business.

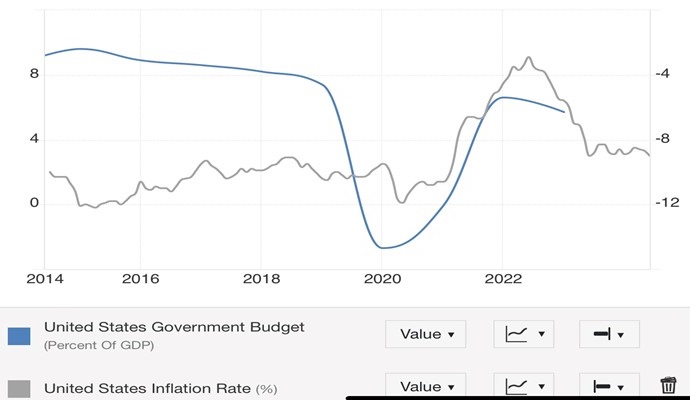

The next chart covers US fiscal and inflation outcomes over the last ten years.

It is worth remembering that the US government has only achieved 2 fiscal surpluses over the last 50 years. More recently from 2014 to 2019, the deficit sat around 4% of GDP and inflation hovered between negligible and 2%.

Simply stated, fiscal deficits did not result in an inflation surge in the US in the period from the GFC to Covid. However, a surging fiscal deficit created by 2 unforeseeable events (Covid and Ukraine), with its far-flung range of global economic and financial consequences (e.g. supply-line disruptions, shortages of goods, labour market upheavals, power price spikes, working from home, etc) resulted in but did not create inflation from 2022 to 2024.

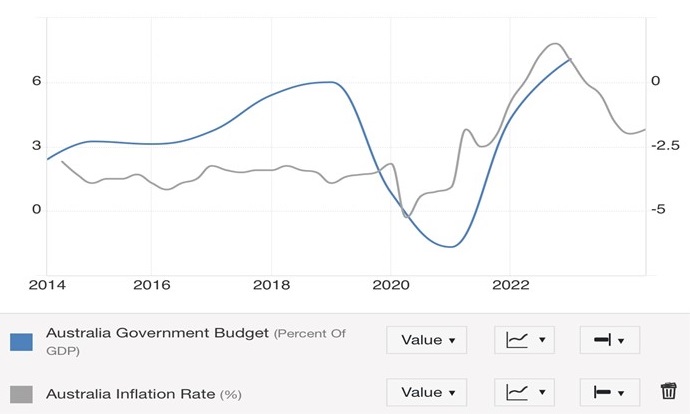

In Australia, observations of fiscal deficits (2014 to 2020) show no correlation with inflation. Whilst commentators point to a surge in fiscal deficits during Covid (7% of GDP) that pre-empted an inflation surge coming out of Covid, that is not indicative of any economic connection. The inflation flowed from supply dislocation, recovering demand and energy price surges. The deficit directly flowed from Covid.

What does this mean for investors?

My suggestion is that whilst investors should note reality, acknowledge Central Bank manipulation, and watch the daily trading noise, they should ignore much of the economic commentary, especially that which originates from traders or proffered by politicians.

There is too little commentary that is focused on the core of investing – understanding the calculation of the risk-free rate of return and how it is or should be calculated?

Bond yields are a fundamental case in point. What is the common explanation for Australia’s 'AAA-rated' ten-year bonds yielding 0.7% higher than 'BBB-rated' Greek bonds? The answer lies in the QE policy of the European Central Bank. It is the result of monetary manipulation and Australia’s dogmatic approach to economic management.

Why is this important?

It explains why bond yields have increasingly decoupled from inflation readings. Also, that the normal measure of risk-free return is less emphatic than it was prior to the turn of this century.

That is not a judgement as to whether this development is good or bad, but rather that it exists and should be acknowledged.

To me this means the following for macroeconomic outcomes for the rest of this decade:

- Government deficits (US, European and Japan) will not be reined in;

- Government debt (US, European and Japan) will remain at high levels;

- Interest rate settings will be driven lower (by Central Banks) to reduce government debt servicing costs;

- QE will therefore return in waves as Central Banks are forced to deal with government debt through manipulating bond markets;

- Government bonds remain low returning asset classes and will struggle to match inflation;

- Economic downturns in major economies (ex-China and India) will be mild and so will economic upturns – think Japan over the last 20 years.

Importantly, it suggests a return to economic management policies that dominated prior to Covid. That in turn drives the tailwinds of 'asset inflation' rather than 'consumer price inflation'.

As for Australia, I have a strong view that continued asset price inflation will mean that the housing crisis will soon overwhelm economic focus and require a complete reset of both fiscal management and monetary policy. Dogmatic economic thoughts will need to be jettisoned to ensure that housing is affordable for future generations.

What should happen?

Policies need to be developed to prepare for a managed decline in housing prices and these include:

- Targeted and aggressive fiscal deficits designed to drive down cost inflation;

- Aggressive fiscal policy aimed at increasing housing supply;

- Well-designed migration policy to slow population growth whilst tooling the workforce for needed essential skills;

- Mild QE policy through the issuance of bonds to move marginal housing loans (negligible equity loans) from the banks to the public sector, so that price declines can be managed; and

- A reset of credit policy by regulating the requirement for higher minimum deposit ratios for housing loans.

There is nothing wrong with fiscal deficits if they are appropriately set for a desired economic outcome. Attacking the cost of living, the cost of doing business and the cost of housing are proper reasons to have a fiscal deficit. However, it does require a breakaway from dogmatic economic thought and an ability to acknowledge the dramatic changes that have occurred in economic management over the last few decades.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.