Mining has always played a major role in Australia’s stock markets, from the first days of informal share markets in dusty mining towns in the early-mid 1800s and up to today. About every 30 years, there is an almighty mining boom when great fortunes are made quickly, followed by busts when fortunes are lost, and many long years waiting for the next boom.

China dominates demand

The most recent mining boom was driven by China’s surge in demand for the minerals it needed for its industrialisation, urbanisation and export manufacturing booms starting in the early 2000s. China quickly became the largest consumer in almost all industrial commodities in the world. Commodity prices soared as supply (exploration, development and bringing new mines into production) takes several years to catch up with surging demand.

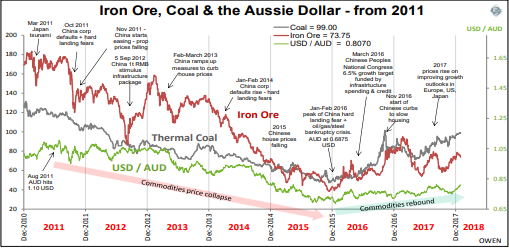

The 2000s China-led mining boom was punctuated briefly by the GFC but thanks to China’s massive stimulus spending programmes to boost activity when the GFC crunched global trade, the mining boom went on to peak in April 2011 after the Fukushima tsunami. The Aussie dollar hit US$1.10 and BHP reached $50. Mining companies went on a wild debt-funded spending spree buying over-priced mines at the top of the market assuming prices would rise forever. They don’t.

Then supply caught up and overtook demand, as it always does. On the supply side, many of the mines developed early in the boom came into production. On the demand side, Chinese urbanisation reached 50% of the population and started to slow, and global demand for Chinese exports reduced in a lower spending post-GFC world. Chinese economic growth peaked at 14% in 2007 but by 2012 the growth rate had halved. Rising supply and slowing demand resulted in price falls and this is how all mining booms end.

Here is a price chart for Australia’s two largest exports: iron ore and steel.

Click to enlarge

The commodities price collapse ... and rebound

Prices of all industrial commodities collapsed by up to 80% in the four years following the 2011 peak. The price falls triggered losses and bankruptcies in miners, oil, gas and steel producers all over the world. These losses caused a global ‘earnings recession’ in the main developed markets including the US, UK, Europe and Japan, and triggered deep recessions and political crises in commodities producing emerging markets. The losses also flowed through to their bankers. Meanwhile Europe and Japan relapsed into recessions, and the collapse of the 2014-15 Chinese stock market bubble and housing boom raised fears of ‘hard landing’ in China, sending commodities prices even lower. The Aussie dollar followed the same path down.

The crisis ended when the Chinese government finally announced a range of new stimulus measures at the Peoples’ National Congress in March 2016, targeting 6.5% growth driven by deficit-funded infrastructure spending. This immediately turned around commodities prices, miners’ share prices and flowed through to rises in company profits and dividends over the past year. The Aussie dollar (and Australian share prices) followed the same path. In 2017, demand was supported by long-awaited signs of recovery in Europe and Japan and continued steady growth in the US.

In 2018, the AUD is now running into expensive territory again, but we see commodities prices remaining relatively firm this year.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.