Bonds seem like a simple investment. In their most common form, you lend your money to a company or a government, and in return they pay you interest on set dates and return capital at maturity (assuming there’s no default). There may be added complexity when quoting a yield, for example, when bonds and hybrids have call dates, so let's look at the different types of yield.

There are four different ways to quote a yield:

- Yield to maturity

- Running yield

- Yield to call

- Yield to worst.

Yield to maturity is a total return calculation where investors plan to hold the bonds until maturity, while running yield projects income for the coming year. However, yield to maturity may not always provide the best insight into the expected return of a bond, especially if there is a call date or there are multiple call dates.

A call date gives the bond issuer the option to repay the investor but it is not an obligation. As some bonds have many call dates, there can be a range of yield to calls, which makes yield to worst the most important measure for investors.

The yield to worst for callable bonds is the lowest possible return for that bond, but there is upside potential if the company chooses not to repay at this date. Yield to worst may be substantially different to yield to maturity or yield to call. Further, as the price of bonds change, so too does the yield to worst calculation.

Four types of yields

1. Yield to maturity (YTM)

The yield to maturity refers to how much a security will earn if it is held to the date of its maturity.

It is the annualised return based on all interest payments plus face value or the market price if it was purchased on the secondary market. Most bonds are issued with a face value of $100, but as they are tradable investments, the price will move up and down depending on a number of factors.

Yield to maturity includes any capital gain or loss if the purchase price was below or above the face value. For this reason, the yield to maturity is considered the most important measure for bullet (non-amortising) bonds or those with a hard maturity date and no call dates, as it provides a point of comparison with other securities. In this case, yield to maturity is the same as yield to worst.

For example, the Qantas June 2021 fixed rate bond was issued at a yield of 7.5%, and is currently offered at a premium to face value price of $114.05. The current yield to maturity is 4.07% compared to the coupon rate of 7.5%. This means that the effective return over the life of the security, if bought today, would be 4.07%, taking into account the current premium price of the security.

The calculation assumes all coupon (interest) payments can be reinvested at the yield to maturity rate.

2. Running yield (RY)

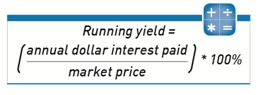

Another measure to compare bond returns is the running yield. The running yield uses the current price of a bond instead of its face value, and represents the income an investor would expect if they purchased a bond and held it for a year. It is calculated by dividing the coupon by the market price as shown below.

For example, the same Qantas bond shown above for the current market price (also known as the capital price) of $114.05 paying a coupon of 7.5% on the face value ($100) gives a cashflow of $7.50 a year. Given this return is achieved at a premium to face value of $114.05, instead of $100 face value, the actual return will be less than 7.5%.

Using the equation above, the running yield would be 6.57% ($7.50/$114.05 x 100 = 6.57%).

As the bond price increases, running yield decreases, and as the bond price decreases the running yield would increase.

Note that running yield does not incorporate any capital gains or losses. As such, institutional investors do not view this as a particularly useful way to analyse bonds.

3. Yield to call (YTC)

Many bonds are callable at the company’s option before the final maturity date. That is, the bonds can be repaid early. For example, subordinated bonds issued by banks and other financial institutions often have call dates, which may be five, 10, 20 or more years until final maturity.

The company has the option but not the obligation to repay at the call date. With some bonds, the call dates continue after the first call date and every interest payment date thereafter until maturity. With others, there may be only an annual opportunity.

If a particular bond’s price rises above par and is at a premium, the chances of an early call may increase. Theoretically, the company can then issue new bonds at a lower interest rate, although the early call price may also be at a premium under the original terms and conditions.

Investors trying to work out the possible returns on callable bonds need to assess the range of returns available, including various yields to call and the yield to maturity to get a sense of what is possible.

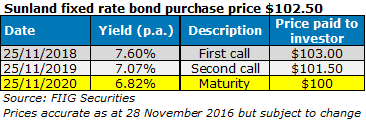

For example, property developer Sunland has issued a fixed rate bond due to mature on 25 November 2020. It is currently trading at a premium of $2.50, so that yield to maturity is 6.82% per annum. But it has two call dates, as the table below shows.

In this case, yield to maturity is the same as yield to worst (see below), both offer the lowest return of 6.82% per annum.

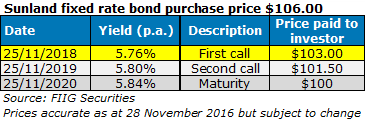

What is key is that as the price of the traded bond changes, so too do the yields. If the purchase price of the bond increased from $102.50 to $106, then the yields would change, as shown below. The lowest possible return is no longer yield to maturity but rather yield to first call.

4. Yield to worst (YTW)

Yield to worst tells what the lowest yield would be if the company calls the bond at the worst possible time for the investor, or if it chooses not to call the bond, delivering a lower yield than if they had called it.

We view this as the superior way of measuring yields, as bonds are there to offer investors downside protection. As such, the YTW is the lowest yield an investor can expect if the company or government does not default.

Yield to worst could be the same as yield to call if the first call is the worst outcome for the investor; it could be the same as yield to maturity if the investor is worst off when the company chooses not to call at all; or it could be lower than both of them where the investor is worst off if the company calls on the second or subsequent call date.

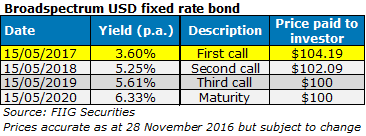

The yield to worst for an investor purchasing the USD Broadspectrum fixed rate bond at its current offer price of $106.25 is that the company calls the bond at the first possible opportunity (resulting in a yield of 3.6% per annum). There is an opportunity for upside if the company does not repay at the expected first call date. The best return is 6.33% per annum at maturity, but it’s likely the company will repay early and refinance in a cheaper market.

Bond investing can be relatively simple when held to maturity, no calls are involved and there’s no credit default, but it’s important for any investor to know which yield is being quoted whenever they buy or sell a bond.

Elizabeth Moran is Director of Client Education and Research at FIIG Securities, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.