The 2017 Federal Budget has turned attention as usual to the issue of government debt. Commonwealth governments ran a surplus during the mining boom from 2003-2008 but it has run deficits since the GFC to prop up employment and growth. The deficits have been funded by running up $500 billion (and rising) in debt. Is this too high? Can we afford it?

The first chart shows the history of annual Commonwealth government balances since Federation. The bars in the top section shows the annual government balance each year. We can see that surpluses (green bars) have been rare indeed. The pink bars in the lower section show debt as a percentage of national output (GDP) each year. The current level of debt at 25% of national output is higher than it has been since 1959.

The government ran rare surpluses during the mining boom from 2003-2008 thanks to high commodities prices but since the GFC a succession of big-spending governments have run up deficits to prop up employment and growth. Strategically timed spending sprees on ‘pink bats’ and ‘school halls’ meant we narrowly avoided an economic recession (arbitrarily defined as two consecutive quarters of negative national output growth), but the cost was a build-up of national debt that will take decades to repay.

Is the current debt to GDP ratio too high?

The main debt build-ups were due to the massive deficit spending in the two World Wars. The ratio of debt to national output also increased during the 1930s depression but it was not because of big spending and borrowing, it was because of the massive contraction in national output.

In the first half of the 20th century, Australia was seen as a high-risk borrower in global debt markets, suffering a default and full-scale Greece-style debt restructure in 1931. Australia regained respectability as a borrower in global debt markets after the post-war economic boom reduced debt in the 1950s.

The current level of Commonwealth government debt relative to national income is not high in historical terms but it is high in post-war terms. It is lower than almost every other country in the world today - but that doesn’t make it right. The current $500 billion pile of federal government debt is costing tax-payers $16 billion per year, or $44 million every day, or $1.70 per person per day. This sounds a lot but there is more to the story.

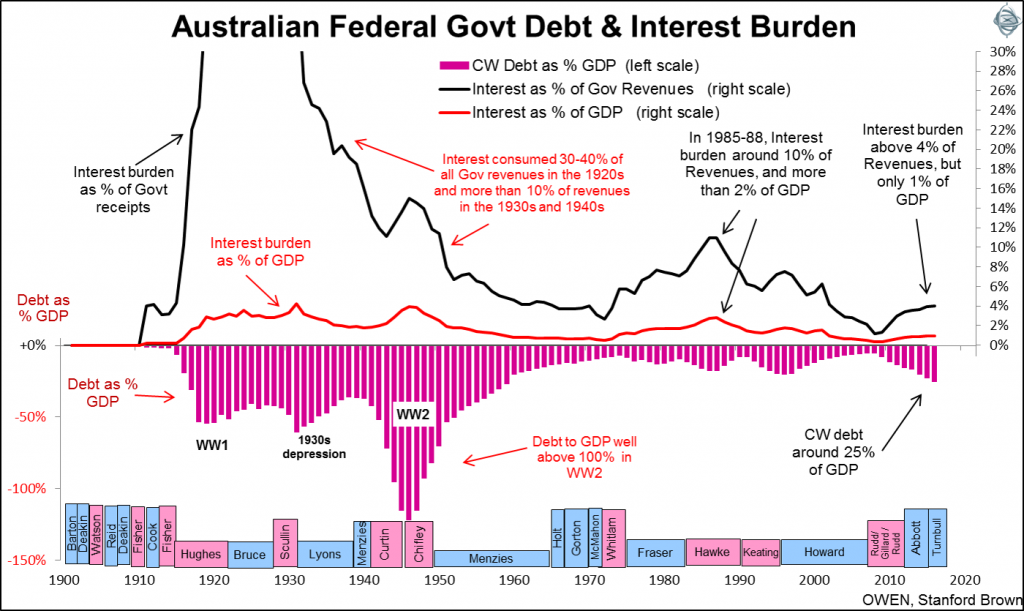

More important than the level of the debt is the affordability of the debt. The second chart shows the cost of servicing government debt in the upper section of the chart.

Click to enlarge

Here we see the cost of interest on this debt as a percentage of national income (GDP) in the red line and also as a percentage of government receipts (mainly tax revenues) in the black line.

The current interest burden is modest and affordable, at 4% of government revenues and just 1% of national income. This is lower than almost any other time since before World War 1, and lower than almost every other country in the world today. Market yields on government bonds have been rising since the middle of 2016 after the Brexit vote but are still at low levels. Rising bond yields don’t translate into higher interest payments until each bond matures in the future and is re-financed by another bond at a higher rate, which in some cases is 30 years into the future. Even if bond yields rise rapidly the interest cost will remain low for many years.

Based on affordability, the current debt is manageable

If the Commonwealth government were a company the board would be sacked for having a ‘lazy balance sheet’ and not borrowing enough to invest in productive assets for future growth.

But here’s the problem. Investing for the long-term future requires coherent vision, long term commitment and willingness to make tough decisions. These critical qualities have been sadly lacking in the recent succession of short-term revolving door governments in Canberra.

I don’t see this improving any time soon. Voting power continues to drift in favour of the aging population of people who have not saved enough for their retirement, at the expense of the young who will have to pay for the deficits for decades to come. The current addiction to debt and fear of electoral backlashes from painful reforms will probably continue. But why worry? About every 30 years, a mining boom comes along that delivers freakish commodities prices and windfall revenue gains.

The windfall revenue gains from the last mining boom were squandered on middle class welfare that is proving extremely hard to wind back. Let’s hope our kids and grand-kids handle the next one better.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at privately-owned advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.