Value index funds have a fundamental flaw.

The problem is not in the principles of 'value investing'. Those are sound, and they trace back to at least 1934, when Benjamin Graham and David Dodd published Security Analysis, where they argue that investors should “be concerned with the intrinsic value of the security and … discrepancies between the intrinsic value and the market price”. Buying stocks at a discount to their intrinsic value makes sense.

For decades, researching companies like this was the only real way to engage in value investing. That changed in 1992, when Eugene Fama and Kenneth French identified the value 'factor' as a source of market-beating returns. If you simply closed your eyes and bought each company that trades at a low multiple of its book value, you could beat the market. Over the very long term, this factor approach to value investing has worked, too.

That didn’t escape the notice of index providers and asset managers, who started creating products to harness the value factor. Today, hundreds of billions of dollars are invested in value index funds and value exchange traded funds (ETFs).

The source of the problem

So if the principles of value investing are sound, and the factor approach works too, what’s the problem with value index funds and ETFs? The issue is in how the simplest and most widely-tracked value indices are constructed.

The world’s biggest value ETFs track major indices such as the S&P, MSCI, Russell, and CRSP. To build their value and growth indices, each of these providers start with two assumptions that have profound consequences:

- Value and growth are opposites.

- A stock’s weight in the value index plus its weight in the growth index should equal its weight in the ‘normal’ market index.

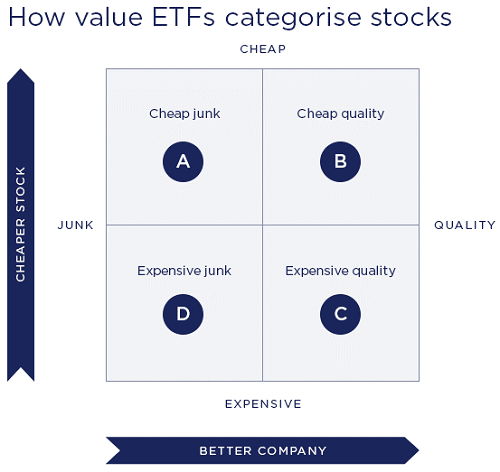

Though the shape of the diagram varies, we can argue that the methodology used has a framework that looks something like this:

How value ETFs categorise stocks

Source: Orbis

For each stock, the index provider looks at one or more valuation measures, like price-to-book, price-to-earnings, and dividend yield, and then ranks all the stocks in the universe. The cheapest stocks get a high ‘value score’ and end up in the top half of the diagram above.

And because many people are interested in growth shares as well, the index providers do a similar exercise with fundamental metrics such as earnings growth. Stocks with the best fundamentals get a high ‘growth score’ and end up on the right side of the diagram above.

So far, so good. In a simplistic way, we know which stocks are cheap and which companies are good.

Why can’t value and growth be friends?

The trouble comes with the next step.

To decide whether a stock should go in the value index, the growth index, or both, the index providers look for purity. Remember, this pre-determined framework sets up ‘cheap stock’ and ‘good company’ as opposites.

In a way, pitting value and growth against each other is similar to assuming that the market is efficient. Cheap stocks must be cheap for a good reason, and expensive ones must be expensive for a good reason. You always get what you pay for, and you always have to pay for what you get. However assuming this sort of efficiency goes against the whole purpose of factor investing!

In their search for purity, the index providers don’t just put all the cheap stocks in the value index as you might expect. Instead, the clearest candidates for the value index are stocks that have high value scores and low growth scores. Rather than calling this ‘value’, you might call it ‘value and anti-quality’. Or ‘cheap junk’. These stocks, we believe in quadrant A, are the core of every big value ETF.

The same thing happens on the growth side. Growth ETFs do not just buy the companies with the best growth. They focus on stocks that have high growth scores and low value scores. Growth and anti-value. Expensive quality only - the stocks in quadrant C.

The rest of the shares aren’t pure. They’re either value and growth, in quadrant B, or neither value nor growth, in quadrant D. These shares get their weights split between the value and growth indices. No stock is left behind!

Strange results

Think for a moment about your perfect stock. For most of us, it would be a profitable, fast-growing company trading at a dirt cheap valuation. In other words, the stock would sit squarely in quadrant B - cheap quality. Buying these stocks is such a good idea that Joel Greenblatt’s ‘magic formula’ book has sold hundreds of thousands of copies. But magic is not what you get in a value or growth ETF.

Instead, you get a bizarre compromise. For the value index, we’ve identified the cheap stocks, and then downweighted the ones with good fundamentals. And for the growth index, we’ve identified the good companies, then downweighted the ones that are cheap. Neither the value nor the growth ETF gets all of the best stocks, and both of them share the expensive junk—stocks that really ought to be left behind. That may be elegant for the construction of an index family, but it is far from ideal if your goal is attractive returns.

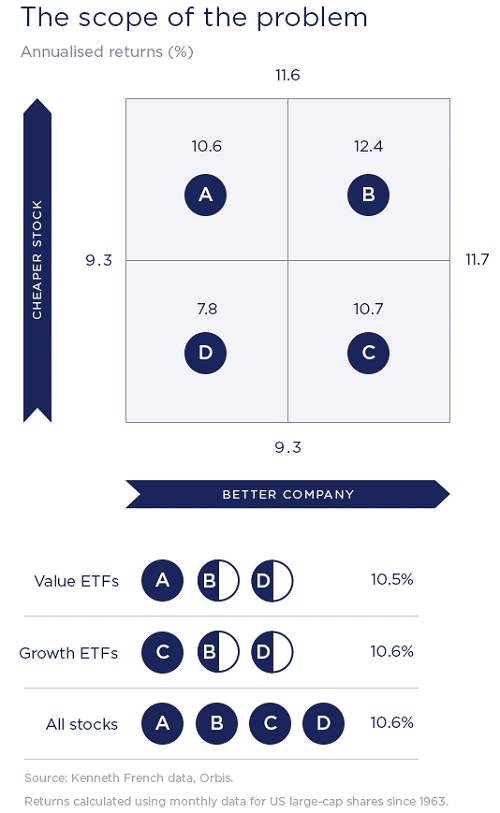

The scope of the problem

We can quantify the hit to investors’ returns, using factor data from Kenneth French. Here, we’ve substituted profitability in for growth as a measures of “good companies”, but the returns here are highly correlated with those of commercial value and growth ETFs. And while this data is for the US given the longer available history (back to 1963), the same patterns hold for global shares over a shorter horizon.

From the numbers, it’s clear where you want to be - buying quality at a reasonable price (B) is the clear winner, beating expensive junk (D) by 4.3% p.a. That amounts to a staggering 10x difference in ending wealth over the full 56-year period. But notice that other things work too. If you ignore fundamentals and buy the low-quality stocks (A and D) or ignore valuations and buy the good companies (B and C), you can also get a reasonably nice return. Value works, and quality works.

But as we’ve presented, you don’t get value in the biggest value ETFs. You get value and anti-quality, or cheap junk. And if you buy cheap junk (A) and (½ of B and ½ of D) or expensive quality (C) and (½ of B and ½ of D), you get the same return as buying all the stocks in the universe. It’s not worth the bother.

Solving the problem

The fundamental problem with value ETFs is that we believe, they target stocks with poor fundamentals. Fortunately, this is a fairly easy problem to solve. Don’t be anti-quality, and don’t be anti-value. Be pro both. Try to buy good companies at low prices, be patient, and enjoy the rewards. In other words, get back to value investing in its original sense - purchasing companies at a discount to their intrinsic value.

Graeme Shaw and Rob Perrone are Investment Specialists at Orbis Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This report constitutes general advice only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.

For more articles and papers from Orbis, please click here.