Housing is expensive in Australia. Measured as a multiple of average wages, Sydney residential property costs nearly 1½ times that of London and over twice that of New York. All eight of Australia’s capital cities are dearer than Boston, Washington, Chicago, and Tokyo.

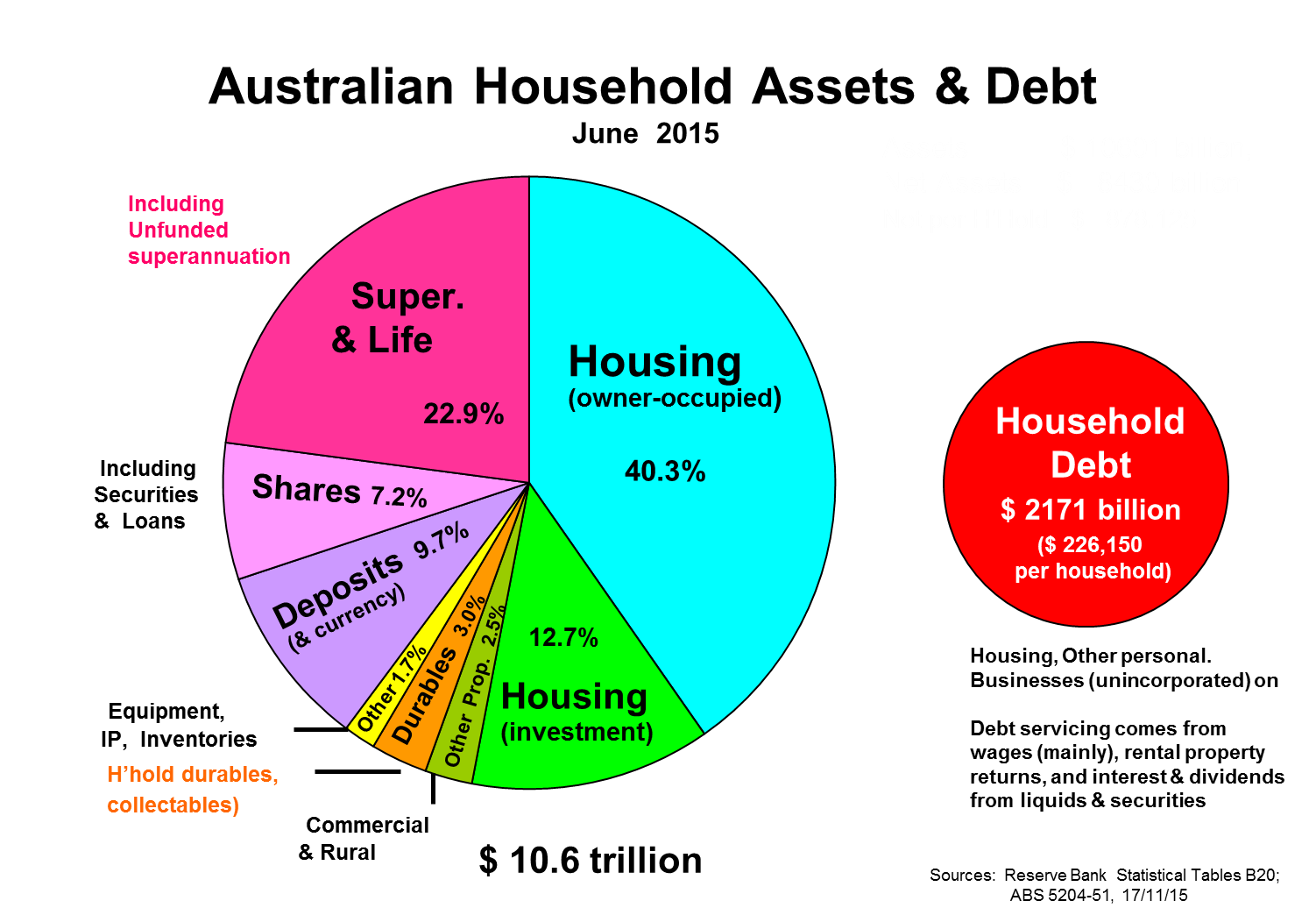

But let’s put housing in a wealth perspective. The diagram below shows the assets and liabilities of Australia’s households using the latest official ABS data (2015). Housing represented 53% of all assets, but a lower 45% if net of mortgage debt. Even adding in household durables (furniture, appliances, cars etcetera) doesn’t bring the total to half of net assets, so the majority of our net assets now resides in financial and commercial products.

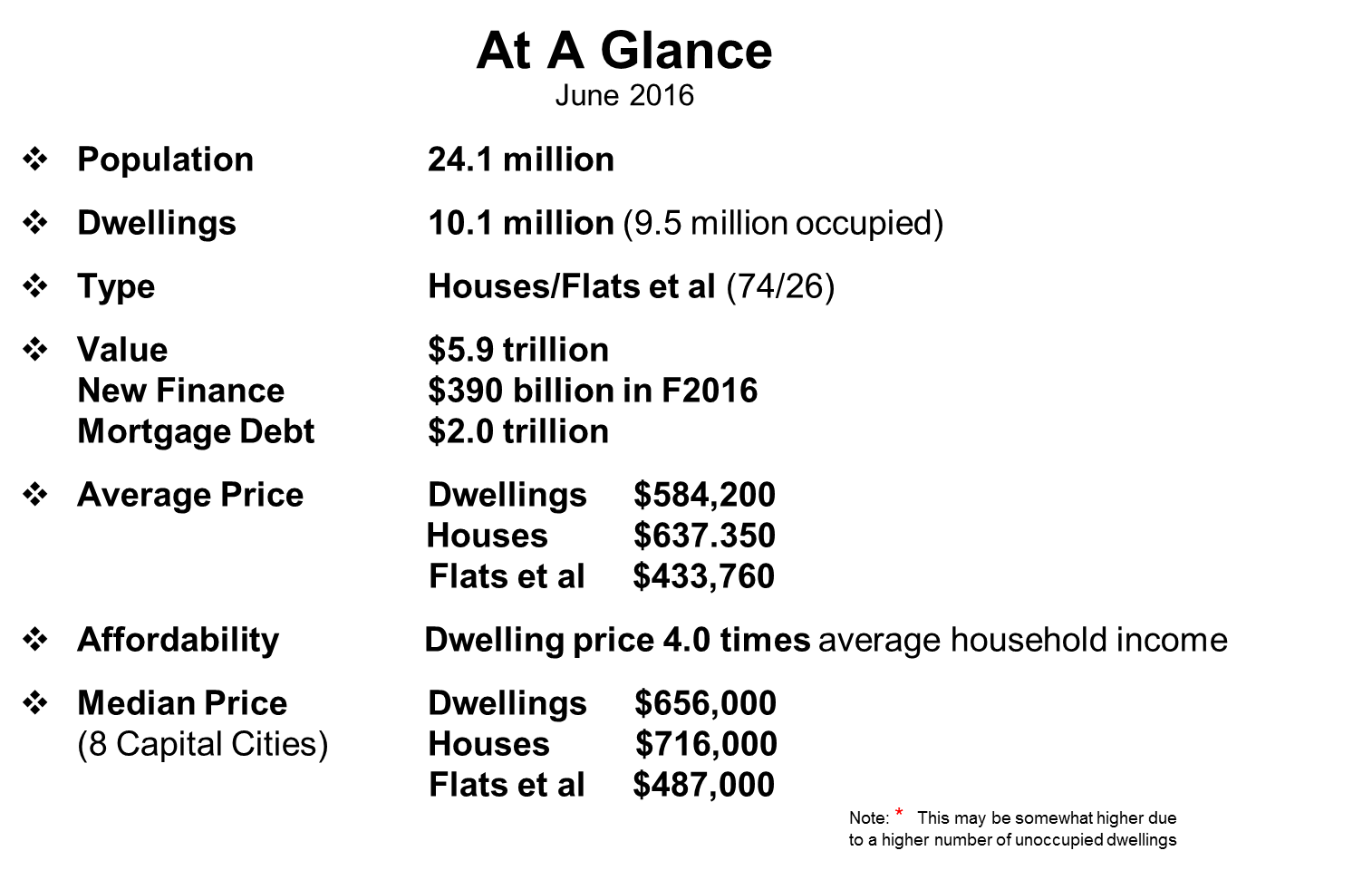

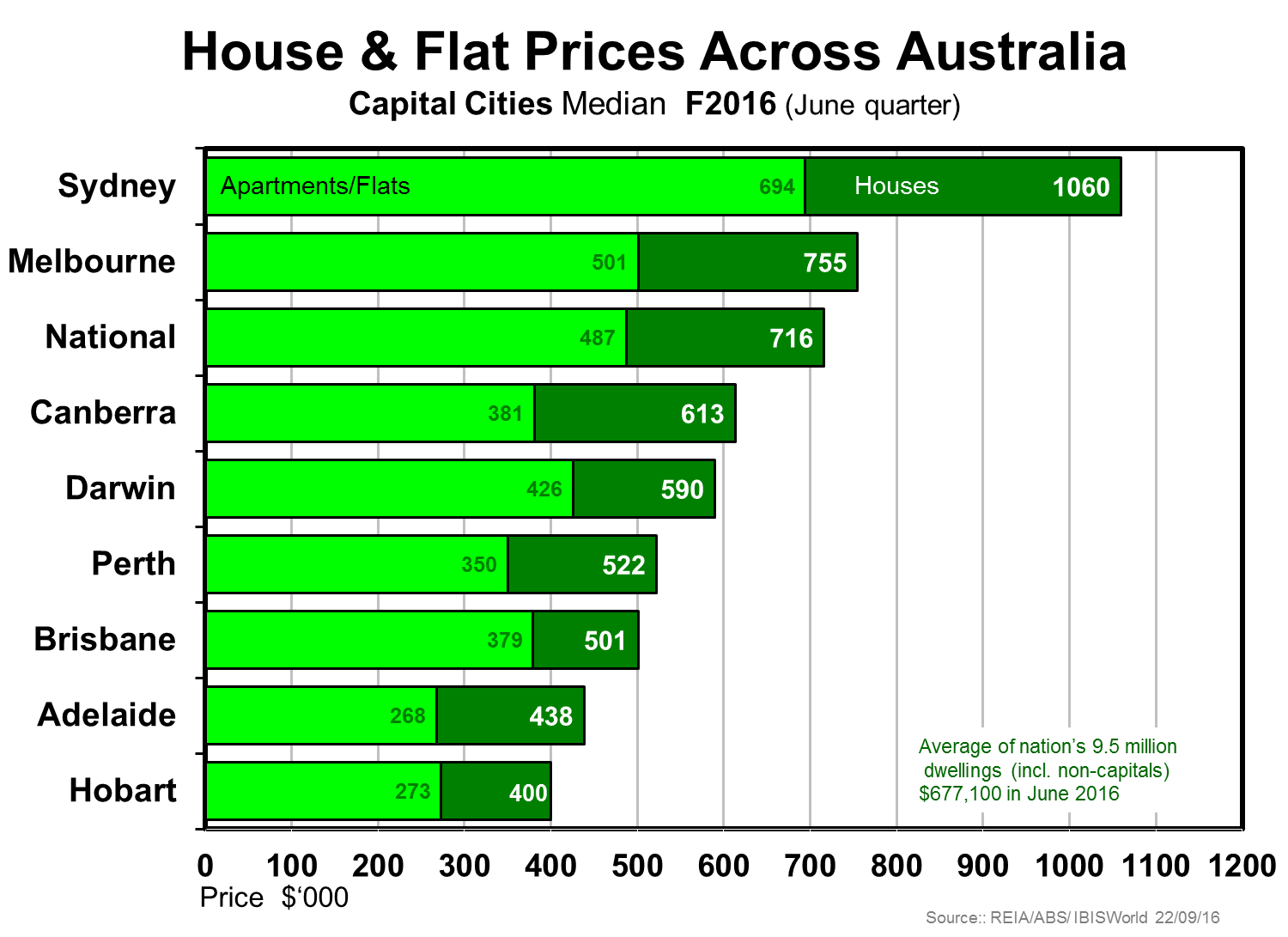

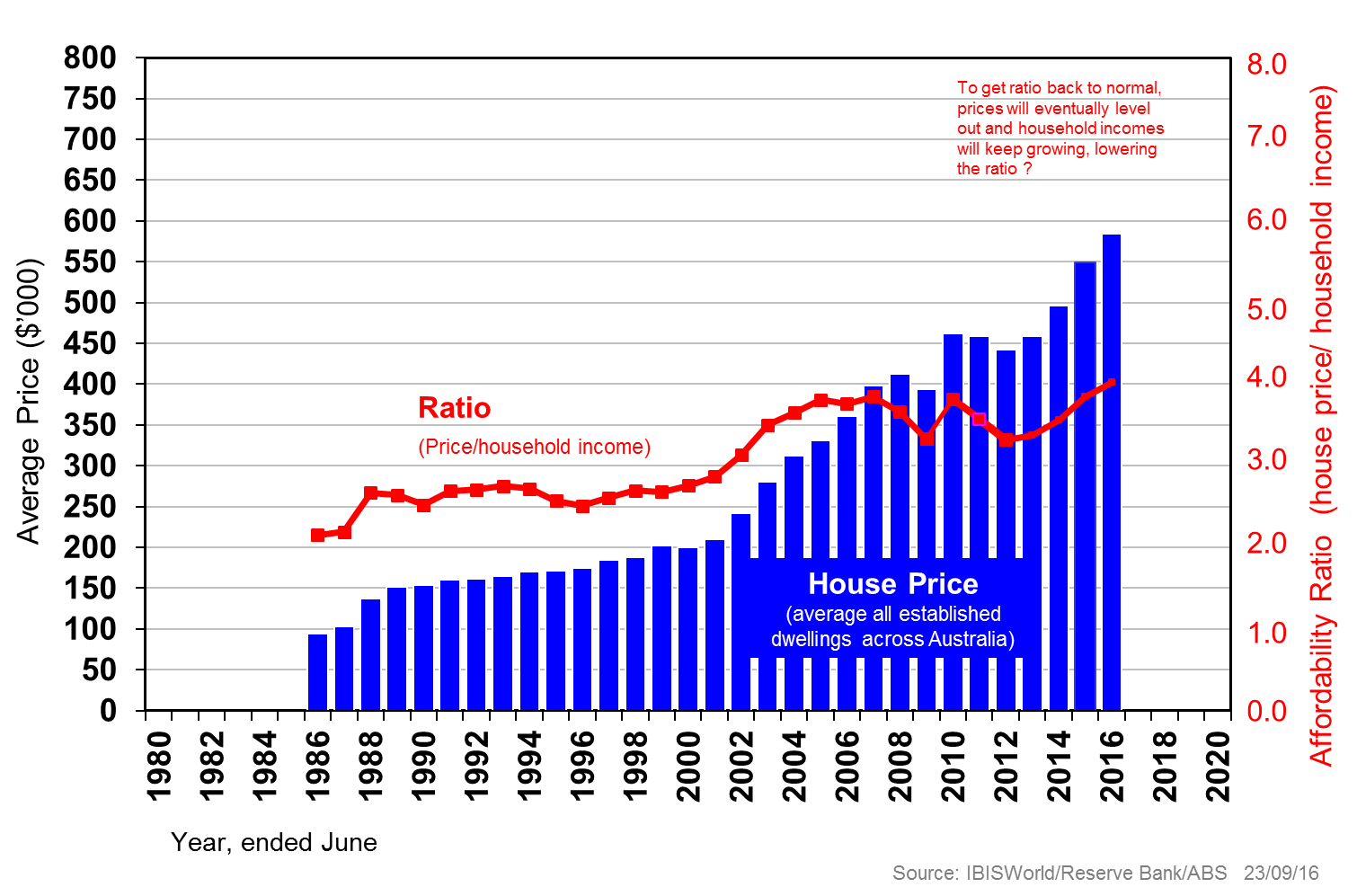

We have over 10 million dwellings which had a total value of $5.9 trillion in 2016, or 3½ times Australia’s annual GDP. There were almost three times as many houses as flats and apartments, the average dwelling costs just over four times average household income, and was valued at $584,000 in June this year.

Our density is just over 2.5 persons per dwelling, half that in 1901. Our dwellings are now much bigger, nearly three times, with three or more bedroom dwellings accounting for almost three-quarters of all residential properties. The table below adds some more perspective.

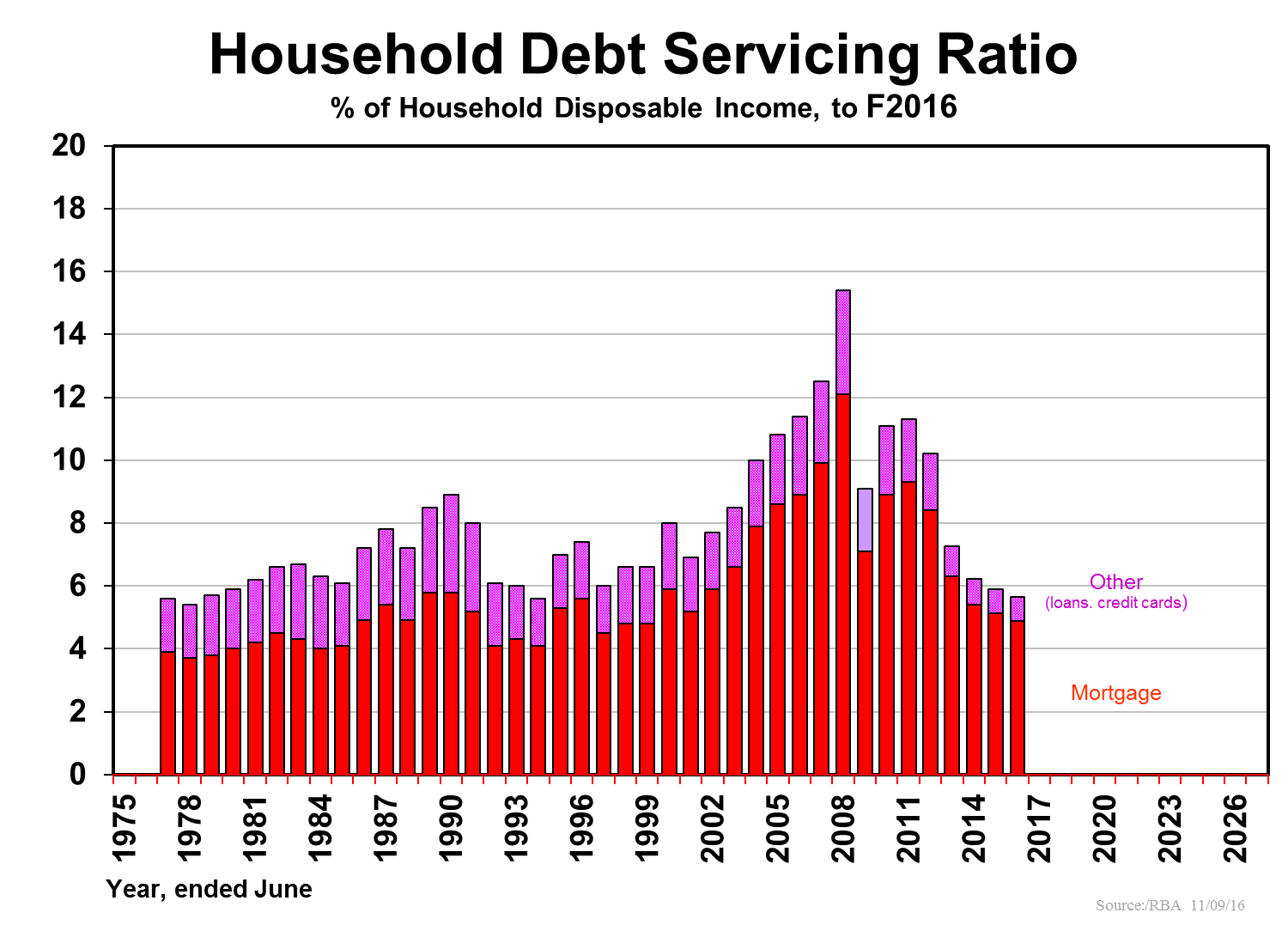

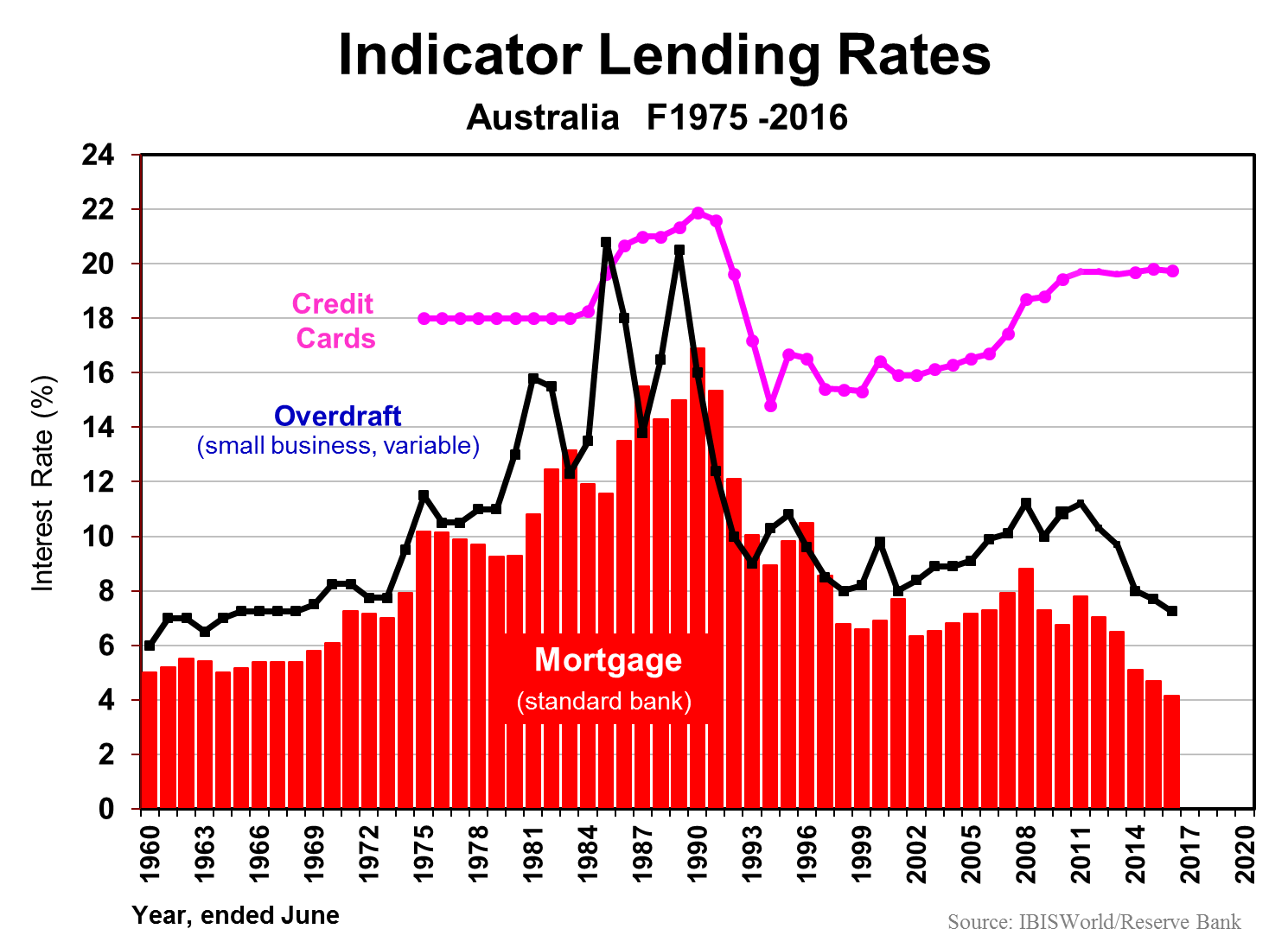

Australians borrowed $400 billion last fiscal year for new housing plus alterations and additions to existing dwellings. We can afford all this on top of existing debt, as the two following charts suggest. Debt servicing is as low as it’s been in five decades, due to record low interest rates.

Our capital cities

Australia’s population is one of the most urbanised on the planet, leaving aside city-states such as Singapore and Hong Kong, but prices across our capital cities vary enormously.

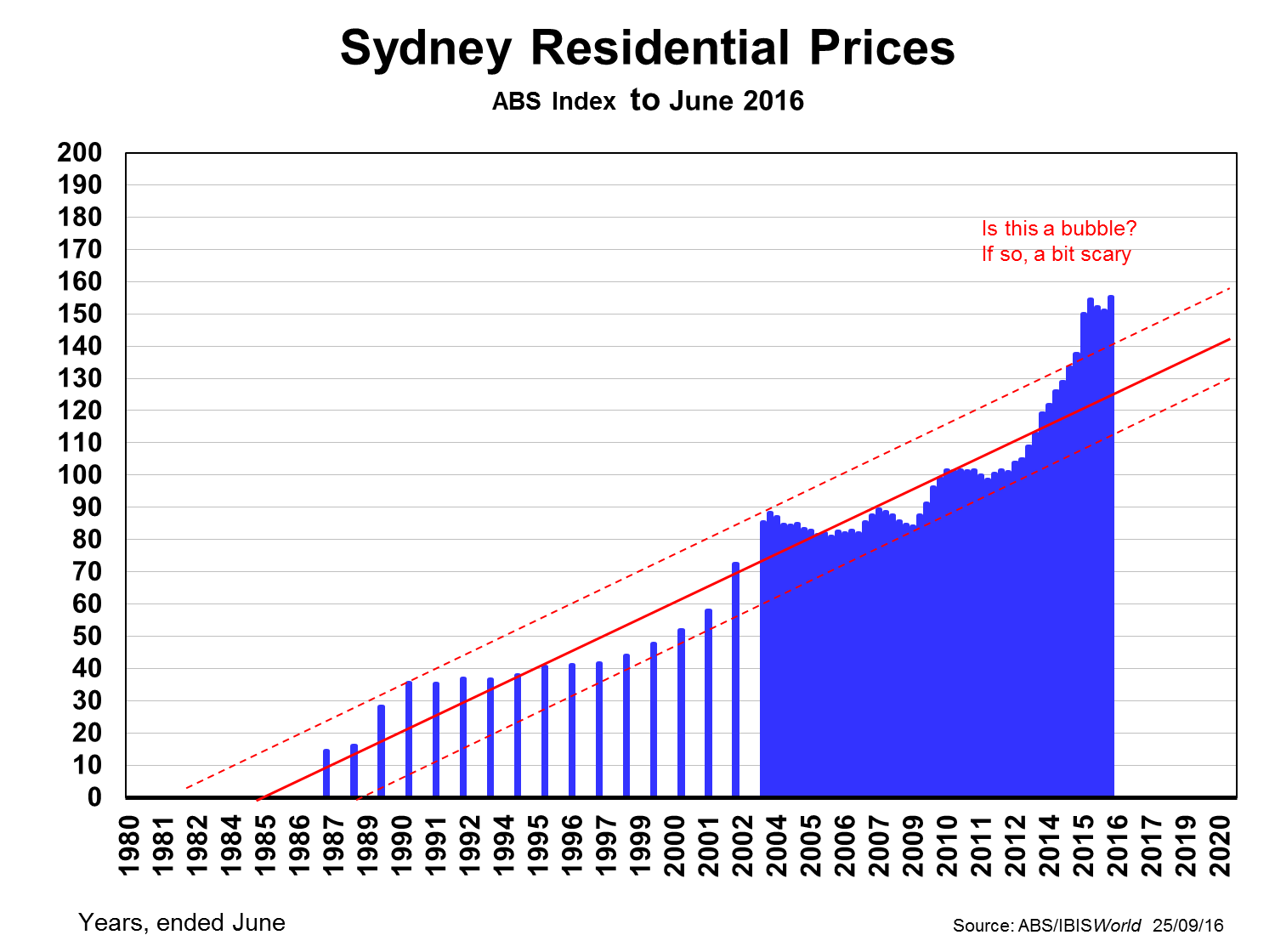

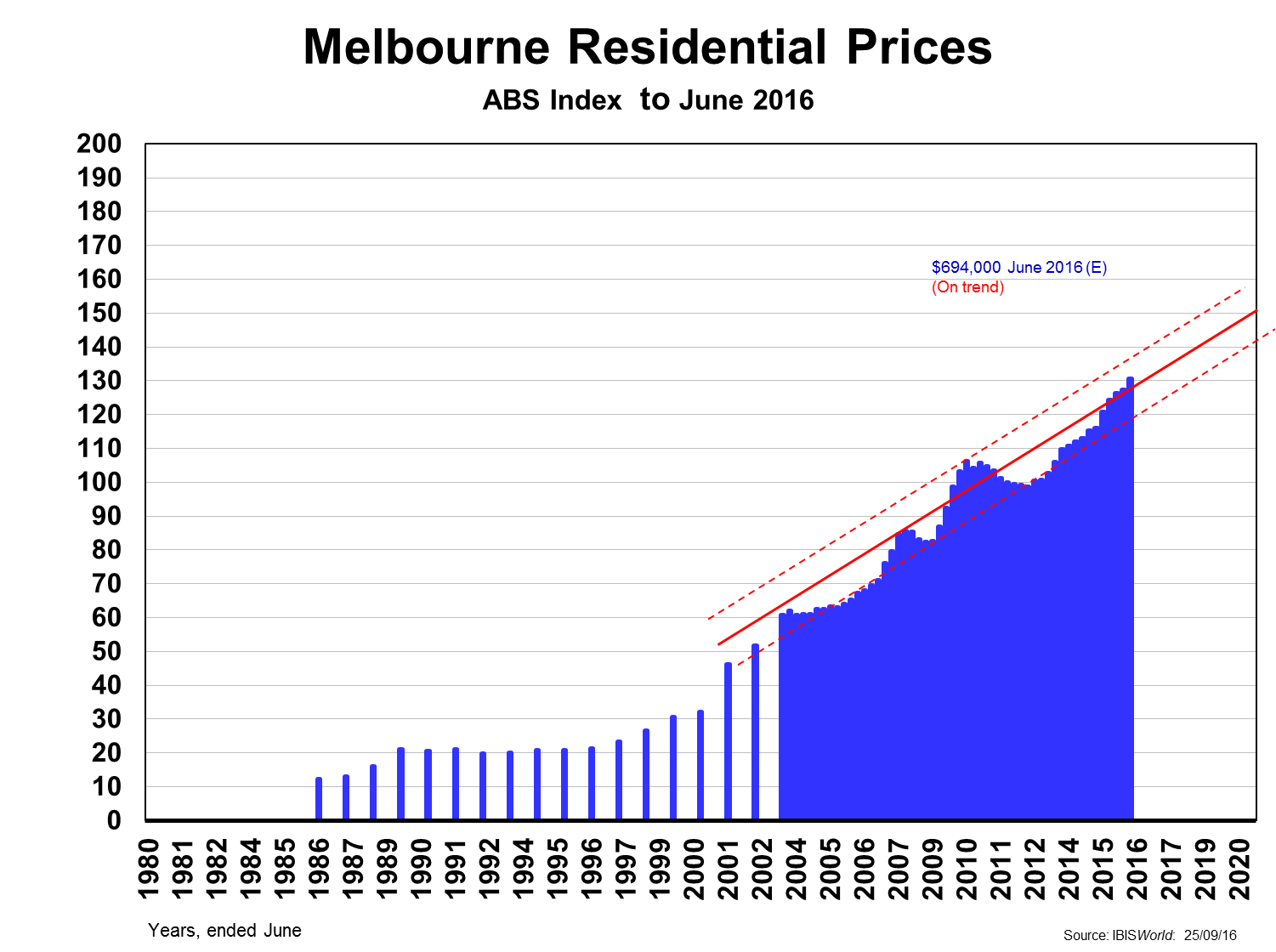

Sydney is the odd-one-out given its prices are so far ahead of the second priciest market Melbourne. The two charts below suggest the degree to which Sydney prices seem to be well over trend compared with Melbourne.

The difference is even more marked when we compare just apartments. Sydney had been under-supplied for nearly a decade, whereas Melbourne had gone into overdrive, leaving Sydney over the past year a sellers-market (prices over-trend by 12-13%) and Melbourne the opposite: a buyers-market, with prices 7-8% under-trend.

The indications are that price growth is abating as we head into 2017. In FY16 prices have fallen a little in Canberra and more in the mining states with their capitals - Darwin and Perth. – falling by 5% or more over the 12-month period.

So what?

Firstly, Australia’s economy is not threatened by its world-leading dwelling prices: they are affordable as seen by the earlier debt servicing graph where the ratio is the lowest in some five decades. The chart below reinforces the fact that we have lived with an affordability ratio in the high range (3½-4 times household incomes) for a decade and a half, without dire things happening.

Yes, Australia’s household debt (mainly mortgage debt) as a share of GDP is one of the highest in the world, but manageable. And our corporate and government debt as a share of GDP are among the lowest, if not actually the lowest. Overall, we are not living too far above our means compared with most other developed nations.

Sydney is the stand-out loner among our capital cities. Its economy and that of NSW are doing well, indeed the best in the nation, but that may not protect it from a dwelling price correction in the year or so ahead, or a longish period of prices flat-lining until incomes catch up to restore equanimity.

Phil Ruthven is Founder of IBISWorld and is recognised as one of Australia’s foremost business strategists and futurists. This article is general information and does not consider the needs of any individual.