The discrepancy between private and public market valuations has been a topic of discussion recently due to the impact of rising risk-free rates. The argument is that private assets, which are long-term and mostly illiquid, may find it challenging to maintain their high valuations as risk-free rates increase. This issue is particularly relevant to superannuation fund performance comparisons because over recent years, superannuation funds have been increasing their allocations to private assets to diversify their portfolios and potentially generate higher returns.

One of the fundamental differences between private and public markets is that there is only ever a finite amount of any private asset, and it is almost impossible to create more exposure to it synthetically via derivatives. The lack of synthetic exposure in private markets makes it impossible for traders to go short and profit from falling valuations in the future. Investors in private markets who are dissatisfied with an asset’s valuation have limited options, as they can only choose not to invest and wait for another opportunity.

On the other hand, public markets offer more flexibility with the availability of index and derivative markets, as well as shorting, which is a common strategy used by hedge funds and macro traders to generate returns. However the use of shorting can lead to increased price volatility in public markets and may not effectively address the underlying issue of misaligned asset valuations.

Cliff Asness, the founder of AQR, a quantitative investment firm, has been an outspoken critic of the misaligned valuations in private markets. In his article “Why Does Private Equity Get to Play Make-Believe With Prices?”, he coined the term “volatility laundering” to describe the underestimation of risk in private equity. While there is merit to Asness' views, it is important to recognise the different impacts of rising rates on various sub-sectors within private markets. Each sub-sector may have a unique effect, and it's essential to differentiate between them for a clearer understanding of the situation.

Commercial property

Commercial property equity tends to decline in value when interest rates rise due to the use of leverage in these investments (usually between 30% to 70%). The increased cost of debt results in lower valuations or capitalisation rates. But, inflation can also lead to higher lease rates, although it is uncertain how much this will offset the impact of higher leverage costs.

In calendar year 2022, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) took note of commercial property valuations as there was a significant discrepancy in the performance between listed funds (~minus 20%) and unlisted funds (~positive 19%), according to data from the Property Council of Australia.

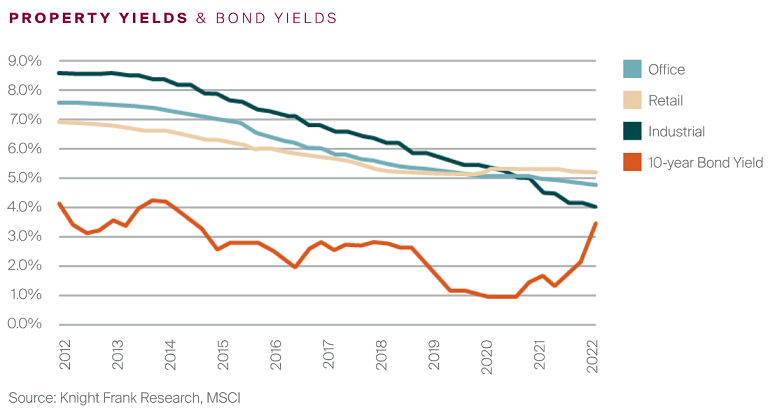

One major challenge with commercial property investments is that capitalisation rates, which are a key determinant of the asset’s value, are typically only reset when a sufficient number of comparable transactions have taken place. If investors can achieve similar yields from risk free 10-year government bonds, this should not be comparable to the capitalisation rate for a real estate equity investment, as shown in the chart below. This disparity between the yields from different types of investments is currently causing concern among investors and regulators.

There is a compelling argument that, if a similar portfolio is available, investors should sell unlisted property at outdated capitalisation rates and switch to listed property.

Infrastructure equity and debt

Infrastructure equity is typically highly leveraged, which means it receives the majority of the upside from the underlying asset. The equity valuation is usually modelled based on long-term cashflows over a period of 30 years or more. However, there is often some form of inflation protection in the underlying asset, which can partially offset the impact of rising rates.

On the other hand, infrastructure debt is typically long-dated and fixed rate, which matches the underlying asset, but does not generally benefit from inflation protection in the underlying asset. The long tenors of both infrastructure equity and debt make their valuations highly sensitive to interest rates and discounting effects, which can impact their overall value.

Venture capital

Venture Capital is arguably the largest casualty of higher interest rates, because the companies in which they invest are often pre-profitability and derive much of their value from long-dated future cashflows that are less valuable due to discounting effects. In 2021, revenue multiples for venture-backed funding rounds reached as high as 100x Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR), but have since dropped to as low as 5x, in line with publicly traded peers. One of the key challenges with venture capital is that valuations are typically only adjusted after each new funding round, which means that outdated valuations can persist for long periods if a company does not need to access new capital in the short term.

Private equity

Private equity involves the acquisition of a majority stake in a privately held company that they believe to be undervalued by the public markets or the current owner. The goal of private equity firms is to improve the company’s performance and profitability through restructuring, growth initiatives and value creation. Once these improvements have been made, the private equity firm can sell the company or its shares through an IPO or other exit strategy in order to realise a profit.

Given that the ultimate goal of private equity is an IPO or trade sale, the reduced valuation multiples in public markets can impact private equity investment, even if the forecast earnings growth is achieved. Private equity funds are typically ten years or longer closed-end funds, which makes it quite complicated to switch into listed equities even if the valuation gap is significant. The growth of the secondary market for private equity funds is expected to help address this issue in the future. Additionally, private equity investments are often made in undervalued and less popular companies, which usually have lower starting multiples, so the impact of multiple contraction may be lower compared to venture capital.

Private debt

Private debt has many characteristics that make it less sensitive to interest rates compared to the private markets sub-sectors discussed above. Firstly, all private debt investments have a legal final maturity date when the original principal borrowed must be repaid at par – they do not rely on the discretion of the manager to sell the investment at a future uncertain date for an uncertain valuation multiple.

Private debt is almost always floating rate in nature, which means that the absolute return increases in yield in line with higher interest rates. Private debt generally has a short credit duration, between one to three years, which means that upon rollover of the existing loans, the prevailing market credit spreads are negotiated into new loan agreements. While the credit spreads do move wider with overall risk sentiment, there is a natural margin cap where borrowing no longer makes sense for equity investors, and a natural floor below which investors will refuse to lend.

Switching between public and private debt is not a straightforward process, especially in the domestic market, as the debt structure of a privately owned company often carries higher leverage and credit margin when it is privately held, and these tend to be reduced when the company goes public. Additionally, there is limited liquidity in the secondary market for private debt investments, as they are normally held until maturity, making it necessary to build a diversified portfolio patiently over time through primary markets.

Summary

Private markets are susceptible to rising interest rates, but the impact varies depending on the specific sub-sector and the duration of the private asset. If the asset has a short duration and its value is realised by a hard-dated maturity, its overall sensitivity to higher rates is relatively low. On the other hand, if the asset has a long duration and the manager has absolute discretion over the investment timeline, its sensitivity to rates is much higher.

Not all private markets can be characterised as "volatility laundering”. The term typically refers to the practice of transferring risk from the public markets to the private markets, where regulations are less strict, and transparency is limited. While some private markets may provide more stability compared to public markets, it is not accurate to categorise all private markets as "volatility laundering”. It depends on the specific characteristics and risks associated with each private market investment.

Simon Petris Ph.D. is Executive Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Revolution Asset Management (ACN 623 140 607 AFSL 507353), a Channel Capital partner. Channel Capital is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This information is not advice or a recommendation in relation to purchasing or selling particular assets. It does not take into account any individual's investment objectives or needs.

For more articles and papers from Channel Capital and partners, click here.