There's no doubt that Australians are big fans of passive investing. Over the last year, the country's ETF market grew approximately 37% to a value of $206 billion. A mere decade ago, it totalled just $12 billion.

According to a recent VanEck survey, more than half of Australian investors claimed that ETFs are their favourite investment vehicle. To put that in perspective, only 3% chose unlisted managed funds or actively managed funds, while less than 2% selected LICs.

Overall, 84% of Australians would recommend ETFs to their fellow investors.

These figures don't come as much of a surprise to me. I've spent a large portion of my career flying the flag for passive investing. I got my first financial services job in 2000, which was around the time that ETFs began gaining momentum.

And it's not hard to see why they're so popular. Australian investors save approximately half a billion dollars a year in fees when they choose ETFs over actively managed funds.

What's more, 85% of active managers don't appear to provide much value for the extra fees they charge.

Armed with this damning data, you might think active management is down for the count. The evidence in support of ETFs would seem insurmountable.

However, passive investing might not be the magic bullet that everyone thinks it is. In fact, I would argue there are signs it is already struggling to keep up in a world that's rapidly passing it by.

To understand why, we need to talk about how the alternatives space - in particular, private equity - has revolutionised the investment landscape.

The rise of private equity

A generation ago, public markets were the only place that companies could typically go to raise large amounts of equity capital. Fast-forward to today, however, and much of that public market capital has been replaced by the private equity industry. This has particularly been the case for new and fast-growing businesses, typically the more exciting parts of the equity investing landscape.

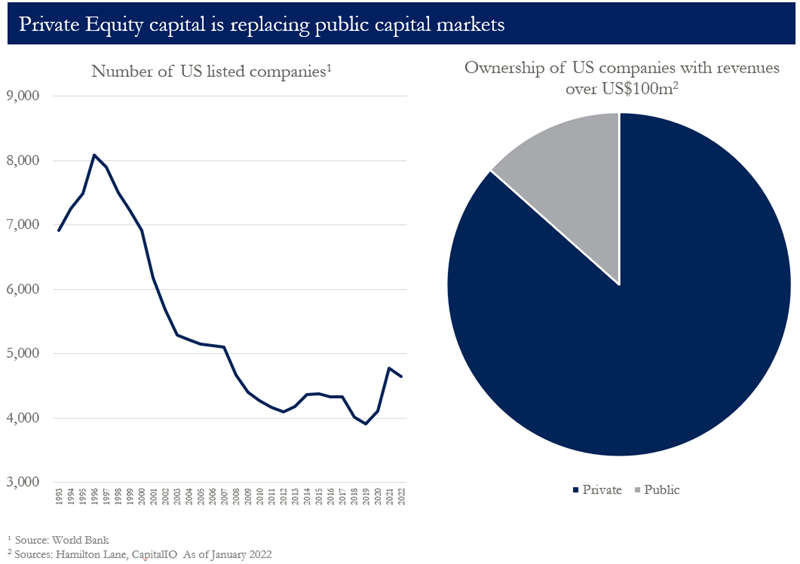

Take the US, for example. In 1996, there were more than 8,000 listed companies in the country, according to the World Bank. This figure had almost halved to 4,600 by 2022. Over roughly the same period, the number of US companies backed by private equity firms has increased more than five-fold from 1,900 to 11,200.

Globally, participation in private markets stood at US$600 billion in AUM in 2000. By 2022, it had reached US$9.7 trillion.

Figure 1: Private Equity dominates markets today

Clearly, private equity is booming. As a result, the lifecycle of companies is far different now to what it was at the turn of the millennium.

Many excellent businesses never make it into the public domain – they are funded, acquired and sold entirely within the private arena. Today, public markets are not only less relevant, but also less representative of the global economy.

What does all this have to do with ETFs, you may be wondering? Well, let's start by defining passive investing and what it's trying to do.

A slice of the economy

Passive investing refers to an investment strategy that tries to track an index. When the first index ETF popped up in the mid-1970s, the thinking behind it was simple but elegant: if the Efficient Market Hypothesis holds true, then stock prices already accurately reflect all publicly available information.

So, rather than incur the costs and time of doing proprietary analysis, why not construct a portfolio that simply replicates the market?

The appeal was obvious. A precisely weighted portfolio could mimic the market and give investors a low-cost slice of the economy as a whole, with attractive returns to match. And that's certainly been the case with passive investing for many years.

But as we've seen, the business landscape and financial markets have evolved considerably over the last two decades. With private equity currently holding such a large piece of the pie, how can index trackers still claim to offer the well-diversified basket of stocks they once did?

The New York Stock Exchange is a good example. The 'Magnificent Seven' tech companies – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – comprise nearly a third of the S&P 500's market capitalisation.

Does that seem balanced? How many financial advisers would sensibly suggest that putting a third of one's wealth into a handful of high-risk, high-return stocks is a suitable strategy for all investors?

If the current direction of travel continues, public markets will only continue to shrink and become even less relevant over time. It's likely that many of the future Microsofts, Googles and Amazons won't even make it onto the public markets in the first place.

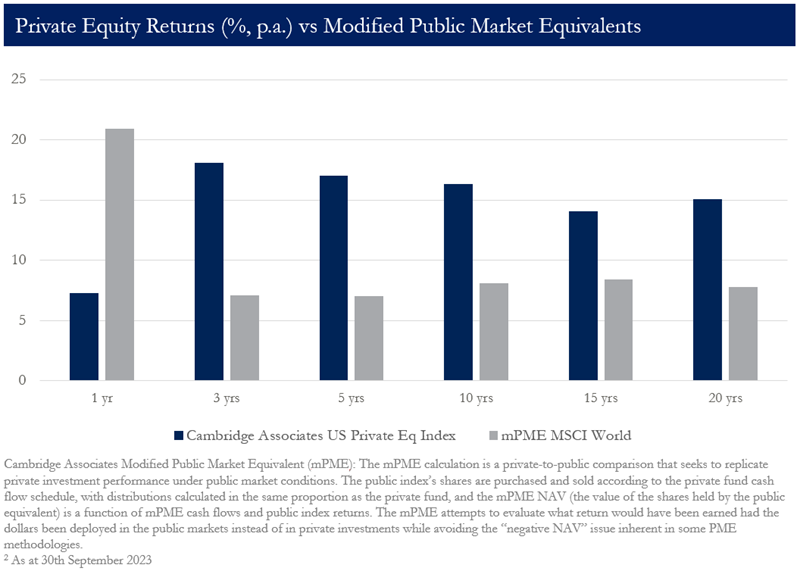

The upshot is that the average retail investor isn't getting a representative slice of the economy through passive investing anymore, and they risk missing out on superior returns as a result. Indeed, research shows that private equity returns have significantly outperformed public markets over almost every time horizon as illustrated below:

Figure 2: Private Equity outperforms public markets

Coming full circle

The world has clearly moved on since passive investing first hit the scene, so can the industry evolve to keep up with modern markets?

Unfortunately, the academic theory that underpins traditional index funds doesn't provide much leeway for product innovation. There's only so much you can do if you're faithfully tracking an index.

This has not stopped the industry from creating a multitude of different passive investment products that focus on specific sectors, markets, themes or trends.

Thematic ETFs, for instance, have experienced steady growth in Australia over the last few years, with a total of $5.4 billion currently invested in them, Global X figures show.

But if passive managers are picking and choosing specific stocks to put in their products, they are straying far from the original philosophy behind passive investing. I'd even argue they've come full circle back to being active managers.

As ever, financial markets continue to adapt and evolve – and so must we. Yes, passive investing can serve an important purpose in portfolios, but favouring it to the exclusion of everything else would be a mistake.

While many active managers don't outperform their benchmarks over the long term, it's worth remembering that the best ones do. On the other hand, all passive managers – by definition – lag the markets they track once fees are deducted.

Ultimately, it would seem to be a mistake to believe that one type of investment strategy is suitable for all people, all of the time. Sensible portfolio diversification should include not just investment diversification, but also product diversification. So don't just buy ETFs; look more widely at high-quality active funds and LICs that give you access beyond just the listed equity space.

Emma Davidson is Head of Corporate Affairs at London-based Staude Capital, manager of the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.