In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the monetary policy mantra was ‘lower for longer’. In a post-pandemic world, that has been replaced with ‘higher for longer’ to keep inflation down.

One would think that if monetary policy worked, there would be no need to keep waiting ‘longer’ to get the desired policy outcome. Despite a zero-interest rate policy and unending quantitative easing (QE), Japan has waited 25 years for inflation to re-emerge. That policy was ineffective and talk about waiting a long time!

Even our own Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) arguably falls into this category of ineffectiveness. After the recent June monetary policy decision, the central bank board indicated the economic outlook was "highly uncertain”. This highlights a lack of confidence in the central banks’ own framework and policy prescription for the current environment. This is of little comfort for the future 200,000 to 300,000 people targeted to lose their jobs in the name of its monetary policy prescription.

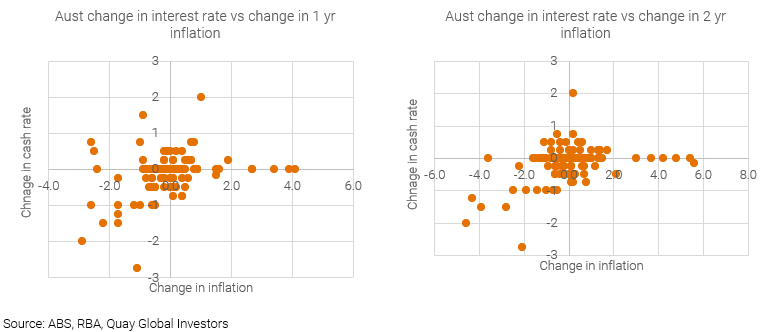

And that prescription may not work to lower inflation into the bank’s 2 to 3 per cent target band. If anything, there appears to be a positive correlation between interest rates and inflation. That is, higher interest rates cause higher inflation, as the charts below suggest.

Source: ABS, RBA, Quay Global Investors

Other examples

Outside of Australia and the US, we have additional examples of the lack of effective impact of monetary policy. Japan is a classic case in point. However, we note some like to make excuses for Japan, such as its old demographics. But we can see inconsistencies between monetary policy and inflation just about everywhere we look.

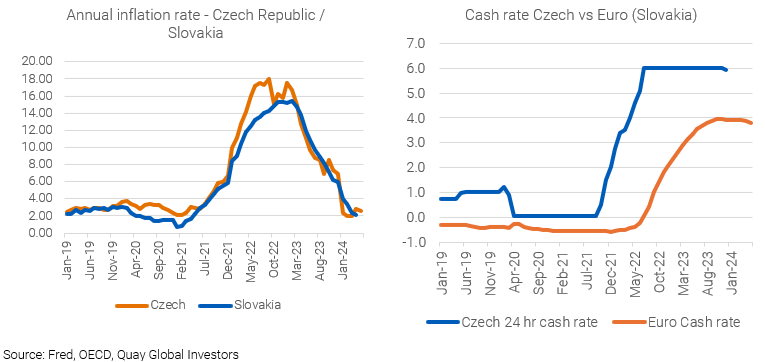

Moving to another part of the world, the charts below highlight the data between the Czech Republic and the Euro member, Slovakia. Both countries share similar demographics and geographies. And as such, both had similar economic growth of around 1% gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2023. Despite the delay in interest rate hikes in Slovakia, and a lower end cash rate, the inflation outcomes for both countries are identical. Surely, if interest rates worked effectively, these like-for-like examples would show different inflation outcomes.

Source: Fred, OECD, Quay Global Investors

Whether it’s the US, Australia, Japan, Slovakia or the Czech Republic, the data simply does not support the idea that interest rates deliver desired inflationary outcomes.

Reasons why rates have little impact on inflation

Generally, there are three reasons for this. First, monetary policy advocates argue changes in interest rates impact borrowers; higher rates are negative, curb spending, and slow the economy with a corresponding decline in inflation, while lower rates are positive. However, as we have written previously in our Modern Monetary Theory Part 2 article, and as highlighted by the Bank of England, loans create deposits. That is, for every private creditor there is a private debtor. Therefore, any pain or benefit felt by a borrower from a change in interest rates is offset exactly by the pain or benefit felt by savers or deposit holders. Higher interest rate may hurt some, but it also allows other people with money to earn more money.

It’s little wonder then why, in the current rising interest rate climate, luxury retailers are trading so well while low-income retailers are struggling. From a private sector income flow perspective, monetary policy is like driving a car with one foot on the accelerator while the other is on the brake. Different dynamics are at work and it's not just a slowdown.

Second, higher interest rates add to the money supply. An emerging excuse for why interest rate policy is not working as intended is that the government is ‘spending too much’, which is working against the central bank’s actions. Of course, the main reason governments are spending is because of interest rate policy.

Take the US, for example. Like most countries, the US government has a net debt position. This means any interest paid is a net positive flow to the private sector. As interest rates increase, this flow accelerates, effectively becoming stimulus. In this context, is there any surprise the US economy recovered so strongly after the US Federal Reserve began to increase interest rates? And since GDP growth began to accelerate, inflation has declined.

Finally, higher interest rates increase the cost of production and prices. One of the long-held economic beliefs is that higher wages lead to inflation. Quite often referred to as a ‘wage-price spiral’, the idea is simple enough. Higher input costs for businesses are readily passed onto consumers – who in turn demand higher wages, and so forth.

What is less discussed is businesses also have a ‘cost of capital’. Higher labour costs can be passed on, why not higher capital costs? We see this today in real estate, especially housing. Current interest policy has resulted in a higher cost of funding, and hence, making new projects less viable. Less supply results in higher prices and rents, feeding into higher inflation.

Best to ignore the RBA

The bottom line is that the use of interest rates policy as a tool for controlling inflation is an accident of history. It should, therefore, come as no surprise its track record is dubious, at best. At Quay, we never position for interest rate policy. It seems jumping from one policy statement to the next is not helpful when investing, especially when those making the statements are equally lost and confused as the impact of their own policy choice.

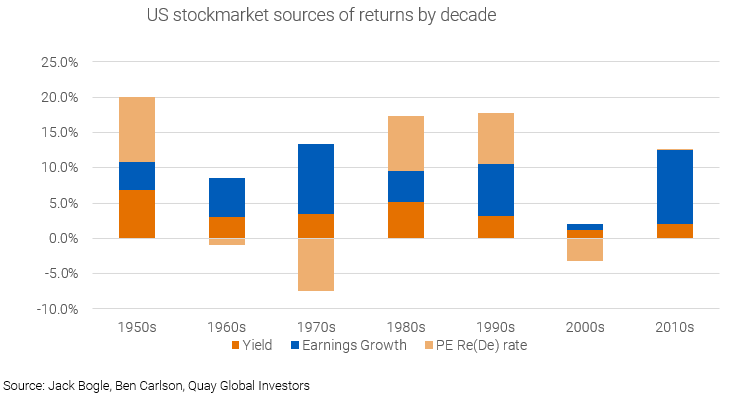

Instead, we fundamentally believe that buying high-quality companies with structural tailwinds and deep discounts is the best way to preserve capital and generate sustainable long-term returns. For long-term investors, interest rates matter far less than total returns driven by earnings growth and dividend yield. And if history is any guide (see the chart below), we’ll be proven right.

Source: Jack Bogle, Ben Carlson, Quay Global Investors

Chris Bedingfield is Principal and Portfolio Manager at Quay Global Investors. This article contains general information only, and does not constitute financial, tax or legal advice. It has been prepared without taking account of your objectives, financial situation or needs.