This article looks at how investors can realistically assess current market challenges and what they can do to achieve meaningful returns with reasonable risk levels.

Overview

The idea that we have entered a ‘low-return’ world now seems to be a consensus. The arguments are based on a combination of fundamental macro factors (a low growth world) and extended structural valuations in both equity and debt markets that suggest both bond and equity market returns face significant headwinds.

Achieving solid real returns consistently in this environment will be arduous. That said, at Schroders we believe beating inflation with a 5% excess real return over the medium term is still an appropriate and achievable objective. This view is based on several key ideas:

- the structural valuation challenges in equity markets are not uniform nor are they extreme (either in absolute terms or by historic standards).

- markets rarely move in straight lines, especially when conditions are challenging; it is reasonable to expect considerable cyclical volatility.

- flexible asset allocation ranges and active management are essential.

- approaches that embed the structural risk of either equities or bonds will likely struggle to deliver consistently. This includes balanced funds, with fixed strategic asset allocations or embedded duration risk (leverage) in the strategy, as the risk around bonds becomes increasingly asymmetric.

A low-return world

The concept of a ‘low-return’ environment is underpinned by a structurally weak global economy with consequences for growth rates, inflation, interest rates, bond yields, and earnings. The bleak growth outlook is due to a number of factors such as:

- high debt levels and pressure to de-lever across the broader global economy

- demographic influences (especially in China, Japan and Europe)

- moderating productivity growth and the potential ‘normalisation’ of a structurally high US profit share

- in Australia’s case, the additional unwinding of the China/commodity induced terms of trade boom, placing significant structural pressure on national income.

Compounding these factors are doubts about policy makers’ ability to effectively manage pressure from a number of areas including:

- the extent to which monetary policy options have already been largely (arguably) exhausted (Europe, US and Japan)

- Chinese debt and overcapacity against the backdrop of an economy undergoing a structural transformation

- fiscal and structural policy that has effectively been side-lined by high global debt levels (both public and private sector) and the absence of clear political mandates

- rising global income and wealth inequality and associated rises in social and political instability.

Valuations matter more than global growth

The correlation between economic factors and market performance is often over-emphasised. Strong economic growth does not necessarily mean strong market performance, whereas the link between valuations and future returns is significant – particularly over the medium to longer term. This is true for both equity and bond markets.

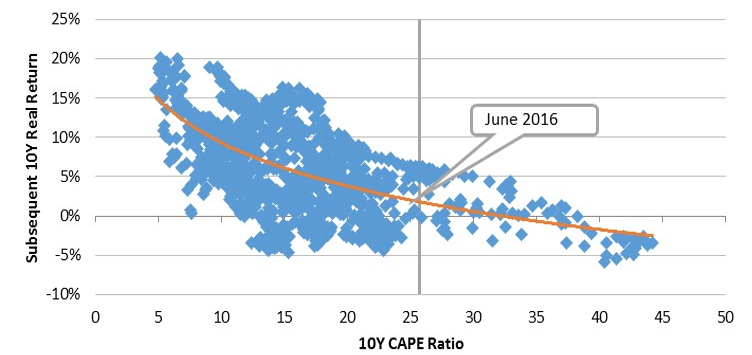

While there is no unique and absolute valuation metric for equities, research shows a strong relationship between longer run, cycle adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) multiples and subsequent 10-year returns for US equities (see graph below).

US CAPE Ratio and 10 year Real Returns for US equities since 1900

Source: GFD, Yale, Schroders. The Shiller PE or Cyclically Adjusted PEs are calculated as price divided by 10 year trailing earnings, adjusted for inflation.

There are two main points to highlight:

- high CAPE ratios have consistently been followed by structurally low returns. The current CAPE ratio of around 23x, while high in an historic context, is well below the 45x level that prevailed at the end of the tech boom of the 1990s, which was subsequently followed by a decade of negative real returns

- while current structural valuations in the key US equity market are extended and consistent with longer-run returns below long-run averages, there is not the same downward pressure on returns that prevailed at past extremes (like the 1970s or 1980s).

This relationship also broadly holds for other markets, but structural valuations are moderately extended in the US, consistent with relatively low (albeit not extremely low) prospective returns. However, in the UK, Europe and Australia, structural valuations are reasonable (around long-run averages) and therefore consistent with longer run rates of return.

While it will be challenging in some areas (especially the US), we expect a positive longer run trend (unlike in Japan over the past two-and-a-half decades or in the US through the 2000s.)

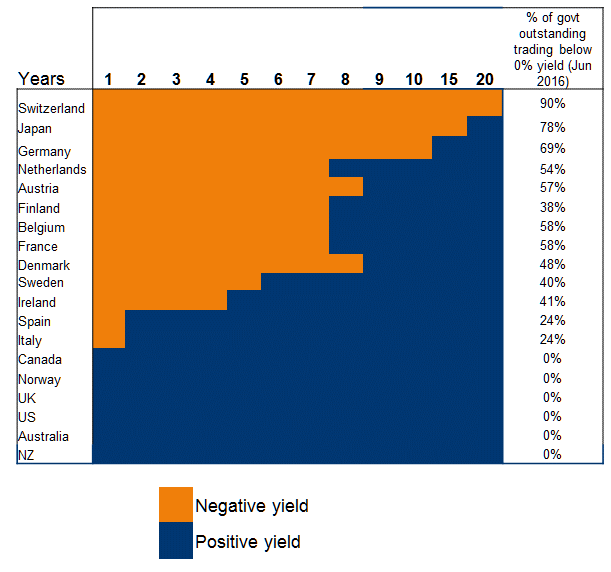

The problem with bonds

Bond markets are potentially more difficult, with record low bond yields implying low/negative returns from sovereign bonds and for assets priced directly from bond yields. This issue has become particularly more acute, with negative yields prevailing across large swathes of the global sovereign bond market (especially Europe and Japan), with extremely low yields in the residual, as shown in the figure below.

Negative yields don’t auger well for future bond returns

Source: Bloomberg, June 2016

While bond returns will vary in the short run as expectations about the future course of interest rates ebb and flow, over the longer term we know with some certainty (in nominal terms anyway) what returns will be. Holding negative yielding bonds to maturity will generate negative returns.

Typically, bonds have been held in portfolios to help diversify equity risk. Structurally low yields limit the ability of bonds to perform this function. The exception is in the context of deflation where the risk to nominal bond yields would still be to the downside. That said, it does have implications for portfolio construction.

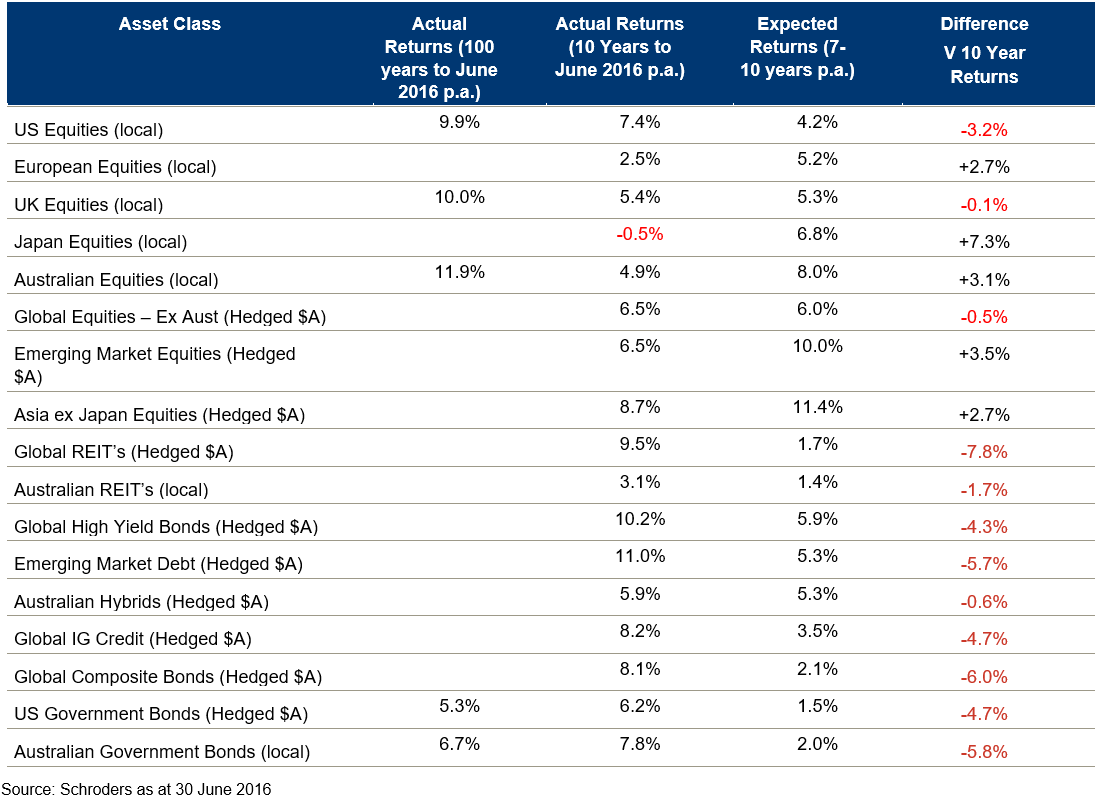

Long-run returns

The issues outlined above are factored into our long-run return forecasts for key asset classes. These are primarily derived from a combination of the broader macro-economic backdrop and an adjustment for long-run valuations. While we expect modest long-term returns from equities, they should nonetheless still be positive in real terms, as shown below.

In summary, while the structural valuation backdrop is challenging, it is not uniform, nor in the case of equities as extreme as it has been historically. For example, while US equities look structurally the most extended of the major equity markets they are far from the extremes that prevailed at the end of the 1990s tech boom. Australian equities, on the other hand, having devalued against the collapse in commodity prices, look like reasonable long-term value. The situation in bond markets is more problematic given prevailing negative nominal and real yields.

Simon Doyle is Head of Fixed Income & Multi-Asset at Schroder Investment Management Australia. Opinions, estimates and projections in this article constitute the current judgement of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any member of the Schroders Group. This document should not be relied on as containing any investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.