We received a question from a reader, Steve, asking:

"There is plenty of talk about inflation as a risk in somewhat qualitative terms (that risk exists, but generally not quantified). The question is how big is the risk. The classic response to inflation is raising interest rates to cool the economy. This also feeds into discount rates impacting the valuation of shares etc. How much would a rise impact the discount rate for share valuation (the risk free rate is only a small part of the overall value used is it not?). If one could estimate the impact of a range of interest rate increases on overall economic activity as well as the impact on this discount rate we could get an idea of the risk to market valuations, going from a qualitative risk to a more quantitative risk."

***

“If you invest in stocks, you should keep an eye on the bond market. If you invest in real estate, you should keep an eye on the bond market. If you invest in bonds or bond ETFs, you definitely should keep an eye on the bond market.” Investopedia

Bond interest rates have an impact on the price of all long-duration assets. The greatest beneficiaries of declining bond interest rates were businesses with earnings way out on the horizon, especially those companies that are profitless today but are forecast to earn a lot in the future.

Of course, the reverse is also true

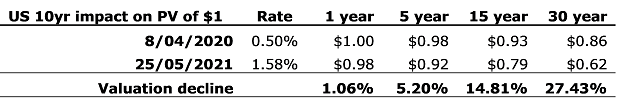

Consider Table 1 on the impact on the present value of future earnings of a rise in the 10 year bond rate from 0.4% in April 2020 to 1.58% in May 2021.

Table 1: Valuation decline from rise in US bond rates

When rates start to rise, intrinsic values start to fall. The rise in bond rates from 0.5% to 1.58%, when applied as a discount rate, results in a decline of 27.4% of the present value of a dollar earned in 30 years.

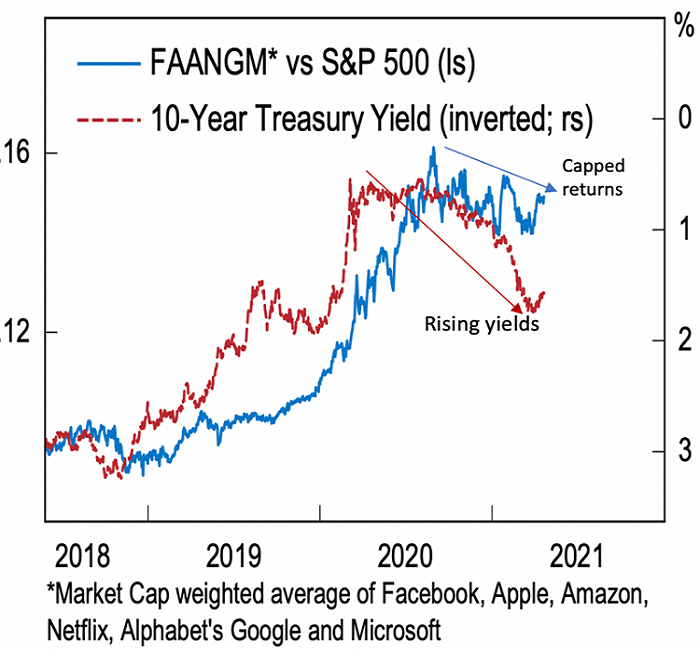

The current (as at 25 May 2021) US 10-year Treasury bond yield of 1.58% is more than triple the 0.51% Treasury bonds traded at a year ago. Consequently, stocks are under pressure and those hit hardest were the same stocks that benefited most when rates were declining, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The real world: Rising bond yields impact long duration growth stocks

Source: Alpine Macro

The rise in bond yields to date primarily reflects a shift in inflationary expectations as well as a rise in real bond yields.

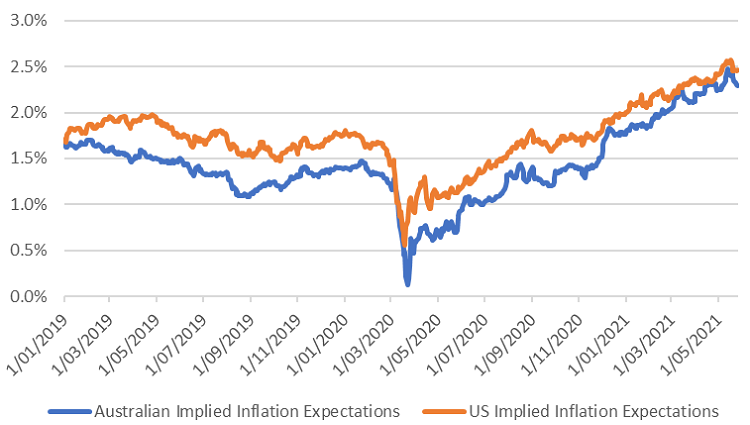

Figure 2 plots the difference between inflation-linked bond yields and nominal bond yields for both Australia and the US markets, providing an indication of the market’s implied inflation expectations over the subsequent 10 years. As Figure 2 illustrates, inflation expectations today exceed the expectations prior to the pandemic in both Australia and the US.

Figure 2: Implied Australian & US Inflation Expectations: 10-year bond yields - inflation indexed bond yields

Source: Montgomery, Bloomberg

While increasing inflation expectations appear to be driving the overall increase in bond yields, a rise in real yields is also occurring.

The positive is the economy is growing

There’s a potential positive to this combination of factors driving bond rates higher. Rising real yields are common coming out of a recession. This is because inflation is still low and rising bond rates reflect confidence in the economic recovery. Consequently, the gap between the bond rate and inflation (real yields) widens. Inflation typically lags economic growth and so the early phase of rising bond yields, coming out of a recession, means the economy is growing, which is usually positive for revenues and an optimistic signpost for markets.

Concerns over inflation however are also a component of the latest spike in bond yields with investors beginning to worry US President Biden’s multi-trillion fiscal packages will spur runaway inflation. Should inflation rise, the impact on long duration stocks – companies not earning anything now, and the impact on companies unable to pass on the price increases - will be negative.

It’s a complicated picture. On the one hand, rising real yields is a positive, on the other, expectations of inflation, a negative. As vaccines roll out globally, economies will return to normal so shifting expectations towards reflation makes perfect sense. Whether it is associated with inflation however is a bet that markets are making.

But markets don’t always get it right. The yield curve is an aggregate market forecast of where interest rates will be in the future, but just because markets anticipate inflation, doesn’t mean inflation will emerge.

Rising rates start as a positive, then bring trouble

History provides a reasonable guide as to what to expect for equities after a recession and amid rising bond yields. Typically, the early stage of rising bond yields reflects optimism about accelerating economic growth and improving business conditions. This is a positive for equity markets generally. During the initial period of recovery both bond yields and equity markets can rise in tandem.

As the recovery from recession matures, continued increases in bond rates prove counter-productive, kerbing economic growth. The yield curve begins to flatten spelling trouble for equities, and presumably long-duration growth assets and cyclical assets such as commodity related assets and commodities themselves.

Unfortunately, history offers no set period of time at which the impact of rising bonds switches from being supportive to being deconstructive. A more useful guide may be to watch the slope of the yield curve. A flattening yield curve has been a useful warnings signal.

Today however, waiting for a flattening of the curve could be problematic because central banks promising to keep short rates at zero renders a flattening of the yield curve doubtful.

One interesting concept proposed by the team at Alpine Macro looks back at history by examining the pace of bond rate rises.

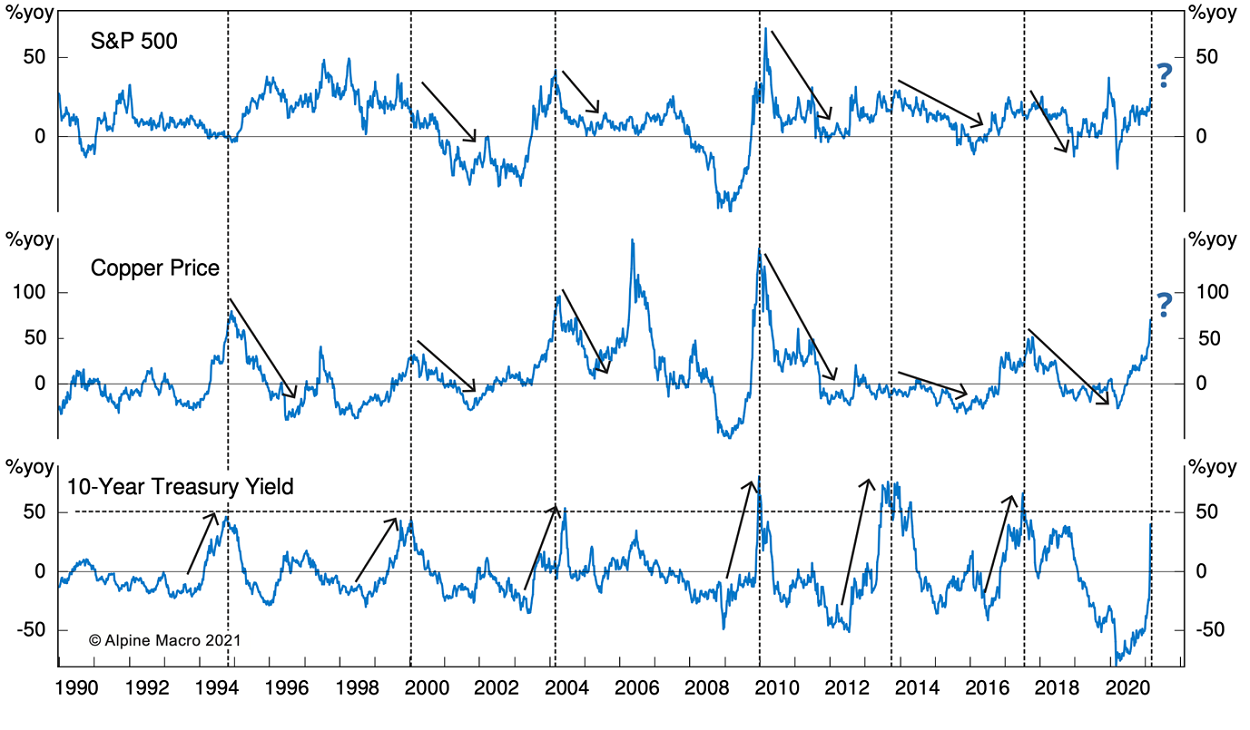

Figure 3: Bond yields, stock prices and copper prices

As Figure 3 reveals, whenever 10-year Treasury yields rose by 50% or more within one year, the move was often, but not always, succeeded by deteriorating equity market performance. Using this historical observation as a guide, the recent near tripling of bond yields might trigger an equity correction.

The relationship however cannot be counted as reliable as there aren’t enough observations and there are periods where a spike in bond yields, such as into 1994, was not followed by poor stock market performance.

Alpine Macro goes a step further, plotting the copper price against bond yields. A 50% plus jump in bond yields tends to push down copper prices. Copper prices are an oft-used gauge of economic growth and historically, falling copper prices amid rising bond yields, may suggest the higher borrowing cost are adversely impacting economic growth.

Today however, copper prices are not retreating, which suggests the higher bond yields are not overly restrictive.

Are company growth assumptions reasonable?

Rising bond yields, hyper-extended Cape Shiller PEs and waves of speculative fervour are enough to scare Jeremey Grantham sufficiently to predict a crash is coming soon. He might be right.

Investors should look at each company in their portfolio and ask whether those companies are reasonably expected to generate strong growth in the next five years. That growth will depend on economic and monetary conditions. Investors should also ask how much of that growth is already factored into prices. Also keep in mind the impact on present values from rising bond rates. This is inescapable. Nothing can replace a rational and continuous assessment of the fundamentals.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.