I appreciated Jeremy Cooper’s recent excellent article on meeting the challenges of longevity risk. Erudite actuaries and investment gurus have long sought investment products which guarantee income for the life of each investor.

While I support efforts to craft better financial products and solutions, we must also make more effort to educate our rapidly-growing older population. There is much they can do to reduce longevity risk themselves. The focus on financial literacy seems to have been most effective at younger ages but not as much beyond midlife. Reallocation of resources into greater longevity awareness is required.

What could be the key elements?

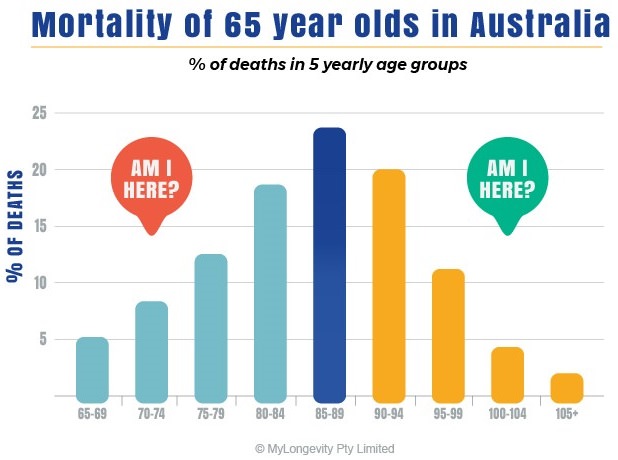

1. Realising that at age 65 (‘retirement age’), over 75% of people are not within three years of the number of years nominated in Life Table expectancies. As shown in the diagram below, there is an enormous range of mortality outcomes, making estimates of how long money will last much less realistic than most people appreciate.

2. Recognising that the rest of their life is likely to play out in three stages: 1) able, 2) less able but still independent, and 3) dependent. Life will be materially different in each stage. For a majority of people at age 65, for example, the able stage is over 10 years, prompting serious consideration of alternatives to stopping paid work too early. This may not be viable as dependency rises.

3. Understanding that the longer they live, the longer they are likely to live, but much of this extra life is likely to be independent. If their prospective lifespan increases, so their dependent phase is likely to reduce.

4. Appreciating that successful ageing is likely to reflect their personal focus on four main issues: 1) exercise, 2) effective social engagement, 3) diet and weight control and 4) appropriate mental challenges.

5. Knowing that indefinite extension of lifespans seems unlikely, but the cost of staying alive will rise to reflect increasingly expensive medical solutions.

6. Accepting that home-based aged care is inevitable for most, and that preparing family and dwellings for this eventuality should be a priority in the able stages of longevity, not when the need becomes evident.

7. Contributing to the debate on assisted dying, recognising the ethical, emotional and financial considerations and expressing a personal view in a way people close to you understand.

8. Factoring in that cognitive issues such as Alzheimer’s disease (now a major factor in the death of older people) appear to reflect earlier life behaviours which many people can address with the hope of deferring the onset.

Averages disguise significant variability

Only 200 years ago, the average baby would not live beyond 40 years old. Babies born today are on average expected to live beyond age 80. Society has made use of this - through better education, communications, infrastructure, laws and governance and greater wealth to invest in living standards. While most people realise this remarkable change is ongoing, few realise what it can mean for them personally.

If we look at a very large group of 65-year-olds in Australia, we know on average how long they will survive. This diagram below shows the percentage of deaths expected in groups of five years. The average survival is 21 years for a 65-year-old. It sits inside the blue column, which represents less than a quarter of the total age group, so the average is not very helpful. At this age, men live about three years less than women.

Success in dealing with longevity risk is more likely to reflect management of the elements outlined above rather than hanging out for financial products which may be a partial solution but will not address the broader opportunities and risks in our longevity for the rest of our lives. People should be empowered to take more control of their personal circumstances, and better education is the key.

David Williams is Founder and CEO of My Longevity. Try the SHAPE Analyser to focus on your own longevity.